Well… I was gonna write about the new double-one Softails and their so-called “Body Control Module.” (Yup—the very same platform that carried the Terminator to fame and glory now has a touch of Skynet technology built in!) Essentially, what was electrical is now electronic and controlled not by basic wires and switches and buttons, as from time immemorial, but by another inviolate little black brain box. This BCM replaces most of the traditional fuses and relays, eliminates high current loads on the ignition switch as well as other switches, reduces the size (gauge) of the wiring and the amount of it (making tidier, tinier bundles of it), allows the use of LED lighting without extra add-on modules and integrates all of the lighting functions with the security system. Sounds nifty on the face of it, don’t it? Thing is—it’s actually just an enabling component technology for a larger overall control system that Harley dubs “HDLAN,” or Harley-Davidson Local Area Network. Just as you might presume, it amounts to an integrated data network, linking the ECM, the BCM, the handlebar switches (including the horn), the instrument cluster and (newly optional for Softails in ’11) ABS brakes. Although ABS doesn’t do much for bikes while leaned over, presumably, it’s still desirable. The great enabler of said ABS on Softails, BCMs use a two-wire system derived from automotive practice using CAN (Controller Area Network) principles originating with the Robert Bosch company, making it one of five major protocols in OBD-II (On Board Diagnostics) used for some time now in the car world. Aside from the gawd-awfully vast wad of acronyms required to even discuss this, it foreshadows what four-wheel gearheads have coped with for over a decade—namely loss of human control over basic functions of their vehicle. Not a trend I personally relish. Much too remote, removed and “Big Brother” I suspect, for most of us nihilistic, Neanderthal scooter-trash types. After all, who really wants their turn signals controlled by computer? What’s really the point (let alone the advantage) of an electronic brain to honk your horn? You tell me! In the meantime, I’m gonna move on to another topic and privately ponder how Sara Conner might react to this news.

I was also thinking of writing about a goofy little bit of technical floss stuck in my mental teeth—this to do with the breathing characteristics of Evolution Big Twins—or the lack of it! A few facts in preamble; namely that Evos are four-stroke engines with two-stoke crankcases, big slugs and an odd firing order, that huff and puff and blow oil (as well as air) everywhere but exactly where you might want it. That’s one! The next is, as primitive as the “solution” might appear (in the form of a timed, rotating breather gear), it was absolutely the toughest aspect of design the engineers wanted to improve on when it came time to create the Twin Cam.

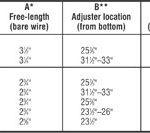

Chart_01

NOTES:

*Until 1987 Big Twins had an external “arm” over the transmission. Only the shortest stock length is shown.

**Iron Sportsters from 1970-1985… all the same!

The issue is this—a timed release of air (or trapping of it, as far as that goes) from dinky, close-fitting cases on older Big Twin engines, however effective back in the day, only works properly over a relatively narrow range of engine speeds. Typically, the system falls apart at any sustained revolutions much above three to four thousand. So-called “pumping losses” go through the roof. At this point, the motor is acting too much like a really inefficient tool that wouldn’t blow up an air mattress, fighting compressed air here and lack of required vacuum there. It gets worse. Although I’m not sure if anyone really understands every aspect of every phenomenon that occurs in the crankcase of a Knuck, Pan, Shovel or Evo at three-quarter throttle (or more), one thing seems obvious—if air control and case pulsing gets outta control, can oil control problems be far behind? (Remember, unlike Twinkies, Big Twins that came before do not separate these functions… at least not efficiently.) The term us old-timers use, even if we don’t really comprehend, is “sumping.” It takes two forms; the one those who park their sleds too long experience; oil seeping past the pump check ball, filling the bottom end and “puking” it out all over your driveway once you finally do fire it up. Then there’s the more insidious variety; a version of the same thing, only it happens stealthily while you’re rolling down the road. It’s this one, the one that leaves enough oil in the cases to impede the progress of spinning flywheels, that got me thinking. The air pumping around like a hurricane inside a running motor can be compressed and sucked and whatnot, but the oil that’s mixed with it cannot! What can happen—and most assuredly does—is the moving air in there moves the oil as well—often to places you don’t want it or conversely away from places you do! (All you need to do to see what I mean is pour a cup of 20/50 onto a table top and blow on it… hard!) With that in mind, since there is only one alternative to the traditional timed, rotating breather gear, I did a little research into that alternative.

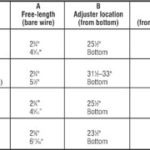

Chart_02

NOTES:

*Every cable company gives slightly different figures for free length, not to mention a different term for it—“free-play,” “travel,” “cable stroke,” etc. It’s the amount of bare wire showing, whatever it’s called and 1/8″ either way ain’t a deal breaker. The important thing to grasp is that free length must be within the right range for your bike—six-speed cables won’t work on five-speeds, rubber-mount Sportsters have more free play than the older ones and so on.

** Adjuster location (and design) may or may not be critical. For 2009 Harley redesigned its clutch cable adjusters to allow a greater range of adjustment, thus affecting the amount of free-length available. Clever, since it meant fewer numbers would fit more bikes for more model years. Other manufacturers have yet to do that, so dealing with them means you need to be more accurate in your assessment of the needed free-length. Most cables locate the adjuster somewhere where it’s easy to get at. If that doesn’t matter to you, or you’d rather hide or reposition the adjuster to some degree, then you can get along with an adjuster that’s not in the “stock” position, as long as the other criteria is correct. (Some cable companies make adjusters that “come apart.” This can be an issue, ironically, with low/drag bars, since oil might travel far enough up the cable to leak from an adjuster situated at a low angle.)

*** This is where it gets crazy. The lengths listed here are simply those in the range that H-D provides—in two-inch increments from shortest to longest. Custom lengths, made to order, are available from several sources. Obviously, the shortest are the low-bar models and the longest are “plus” lengths for high bars. The trick is to learn what length you have, in order to determine what length you might need instead, for a bar swap. For instance, all Touring models since 1996 (according to Harley) have stock clutch cables 62.69″ long. Softails and Dynas have a wider (higher and lower) range of OEM handlebar fitments—thus a bunch more “stock” length clutch cables. Same thing with late-model Sportsters. (On the other hand, four-speed Sportsters, from 1986–1990 had only two “stock” lengths, one for high bars and one for low bars, at 61 1/4″ and 52 3/4″ respectively. Obviously, so-called “plus-six” for the shorter Sporty cable wouldn’t be as long as the longer one is—stock!) This is exactly why measurement is the only proper method to get lengths right!

A note on the “NOTES”—what I’m trying to get across here is that these A-B-Cs are the only criteria that matter! Cables are not rocket science, but the trend towards listing applications via Harley-Davidson’s alphabet soup of model designations and model years just generates a ton of confusion and complexity that’s unnecessary… almost dis-information actually… that makes it seems that way.

S&S Cycle offers a patented “reed-valve” version of this crankcase breather. A brief online interlude will quickly show that people have used it on Shovelheads (with the primary sealed off, like an Evo), on early Evos and —mostly—for late-model (’93–’99) Evolutions. Its improved effect and efficiency is relevant from 500 rpm all the way to 8000 rpm. Now—the plot thickens! It seems, at first anyway, this reed-valve breather was listed as useful for all these bikes. Not any more. S&S only wants folks to use the reed-breather in “head-breather” Evos from 1993 through 1999. Why should this be? Well, for a clue, let alone any sort of answer, one must read (between the lines) the original patent application. I’m convinced that, first of all, the reed breather was developed in response to a specific need that S&S had at the time—namely, to do with concurrent development of their 4 1/8″ bore engines. Again—at engine speeds much above 3000–4000 rpm, conventional “timed” breathing goes all to hell, especially in huge Evo-based configurations—built to rev as high as eight grand! Finding workable timing in a conventional rotating breather was not happening. Enter the reed-valve concept. Two-stroke engines, which “pump” their crankcases like mad, had used them for years, to great effect. What was discovered was, with a slight vacuum applied to the vent line on case-breather type engines, it worked a treat. Since the reeds reacted very well to the real requirements of air pulsing in the engine, rather than theoretical (or imagined) needs and events within and without a high rpm V-twin, it was something of a breakthrough.

But—to get back to the recommended application to head-breathing Evos only—it seems that older engines without that slight vacuum don’t respond as well to the reeds—or vice-versa. How to create the vacuum in older engines, which merely vent atmospherically, without re-inventing the whole oiling system as well, remains a touch problematical. Since I intend to use a reed breather on my 1985 FXR, I’ll have to do more homework and get back to you. So—as promising as reed breathers are—I guess I won’t write about that right now.

Instead, I thought I’d write about the lowly control cable. Invented by a British dude named Bowden well over a century ago, these things are still ubiquitous in the motorcycle world, in spite of any trend towards “fly-by-wire” or hydraulic alternatives. The trouble, in a way, is just that; they’ve been used forever by H-D and in bewildering profusion. There’s no way I can manage an exhaustive treatise on the subject (probably at all, let alone here) but let me try to “clutch” at this much, at least.

You need to know about the specific characteristics of the cables on your motorcycle—mostly when you want to change handlebars. I mean, if you break one, you simply order a “stock” replacement (whether it’s actually the original type or a fancy braided one) so there’s not much to worry about. Changing the configuration of the rider interface is a different story and a lot more complex. There’s a sort of shorthand in “cable-speak” when you need different lengths than your bike came with. You hear terms like “plus-six” or “plus-10” applied to cables required to change from factory handlebars to higher/wider versions. Rarely (these days) you also hear of a “minus-two” or “minus-four” if someone is installing shorter bars, like flat-track or drag styles.

I have a confession to make—I can’t really “speak” shorthand and I hate it when people use it, instead of complete informed sentences, where properly fitted control cables are concerned. Let me say this flat out—the only correct method to use when altering control cables in any way is actual, accurate measurement. Mount the bars of choice, then see exactly how much longer or shorter the cables need be. Fat chance!—at least when reality intrudes; “reality” in this instance being that the majority of folks buy handlebars and want cables (and hoses) to go with them—then and there! Most only guess at what “plus” (or “minus”) might work, particularly if it’s their first time trying to mate this bike with those bars. Even experts, who have a major advantage if they’ve done this sort of thing a lot, sometimes fail to get it right, if the combination is new and they use the “plus” method. Since I can’t prevent it—and few would really want me to if I could—what I’m going to try instead is to “wire” you with some (truly) basic tips for these cable fitments in the hope that you can work out what you really need for a bar swap—the first time around—regardless of method. Can’t go back to Harley’s “stone age” just yet, so we’ll start with 1996 models—and only clutch cables for now. Earlier than that—and more than that (like throttle and idle cables and brake lines) well—it’ll give me something to write about next time! Until then… ah… “bar appetite”!