Hedstrom sets the pace

Popular history has George Hendee witnessing Oscar Hedstrom’s tandem pacer in action during the December 1900 races at Madison Square Garden and he was so impressed that he offered Hedstrom a partnership. Another version dates this a year earlier and has Hendee signing the motor tandem team of Henshaw and Hedstrom to pace races at the Springfield Colosseum for the following season.

In Middletown, Connecticut, 42 miles from Springfield, Massachusetts, Oscar Hedstrom had, by 1895, established a reputation as a custom builder of racing bicycles and was working at the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Co. creating the Birdie Special. In October, Hedstrom changed his club affiliation to team up with another employee, Charles Henshaw, as a professional tandem pacer team and they quickly became known as one of the fastest tandem teams on the racing circuit.

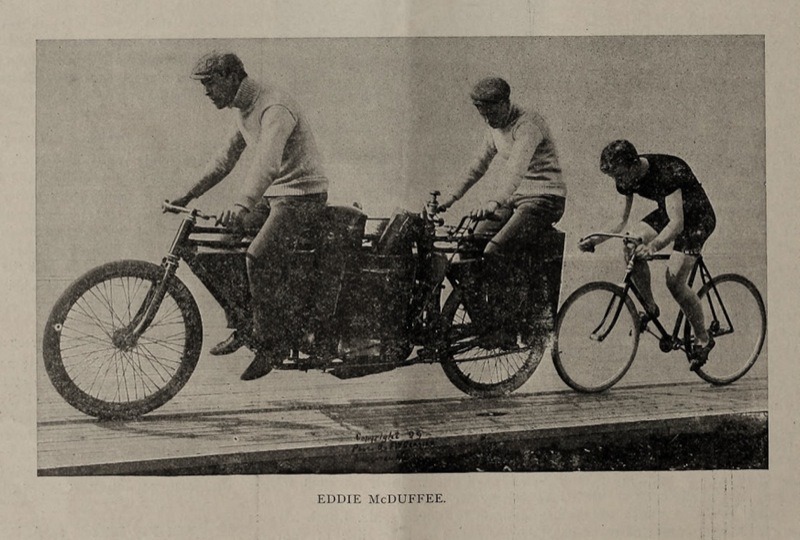

Pacers were teams of men—usually two, but sometimes three or more—on tandem bicycles that would ride ahead of the racer and provide a slipstream to reduce wind resistance. This allowed professional racers to increase their speed and endurance. Professional medium and long-distance stars demanded unlimited pacer teams and often would use 10 or 12 teams per race.

De Dion-Bouton of France had designed a small internal combustion engine in 1896 and placed it in a tricycle. The following year they were producing and selling both the motor tricycle and complete engines. Kenneth Skinner of Boston acquired the sole U.S. distribution rights in November 1897 and partnered with Charles Henshaw to open Back Bay Cycle Company. Allegedly, Hedstrom learned to tune the engines of the De Dion-Bouton tricycles and quadracycles that were imported the following year.

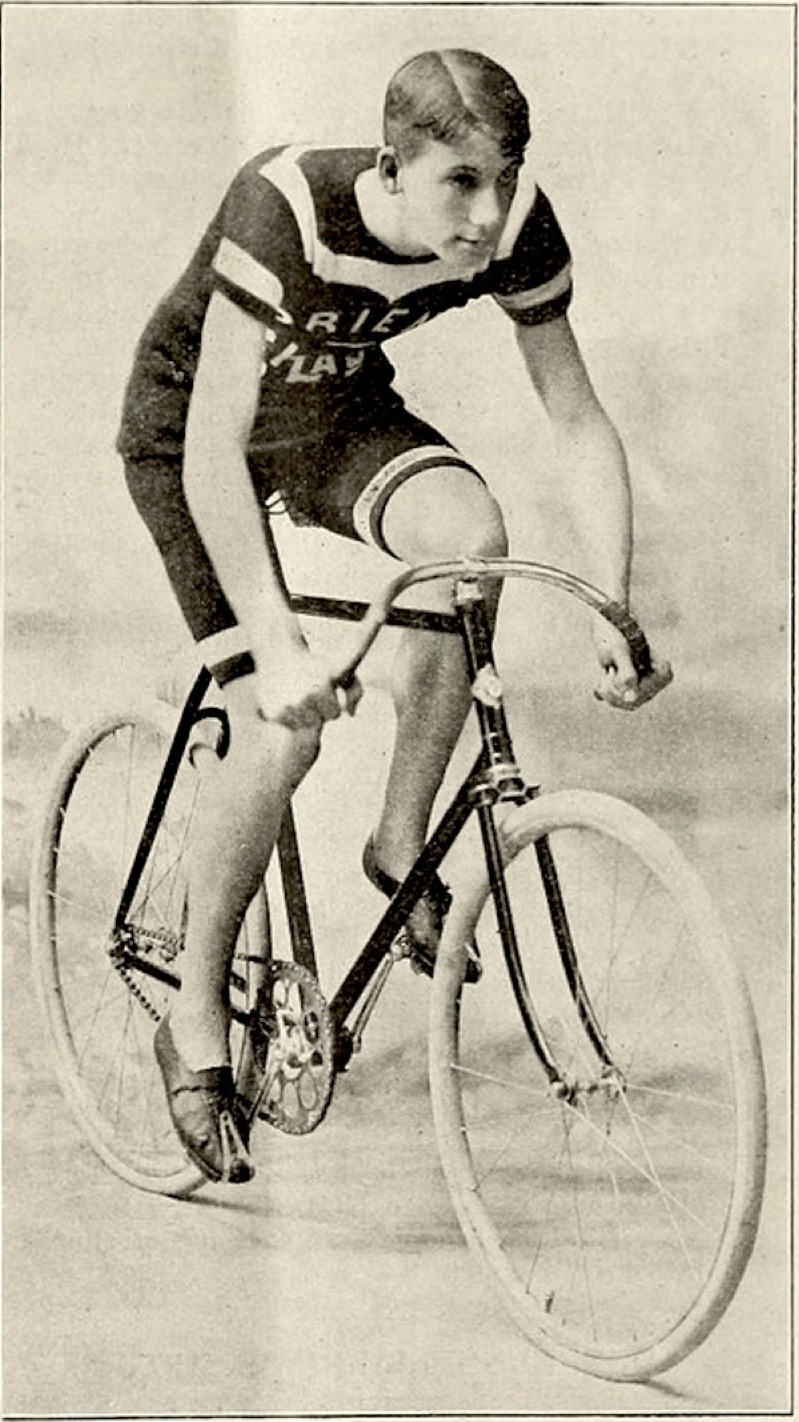

In the fall of 1898, French racers Henri Fournier and Gaston Ricard came to the U.S. and brought with them three motorized pacers: a single, a tandem and a tricycle. The first official bicycle race using a motorized pacer took place at the Waltham, Massachusetts, racetrack in November. The second was at Madison Square Garden on December 3, where Fournier, on the single, paced Eddie McDuffee and also demonstrated his pacer to other racing stars. Between races he rode the tandem motor pacer before a crowd of 10,000 spectators. On the 26th, a 20-mile race was held at Madison Square Garden between Fournier on his solo machine pacing Jay Eaton and Teddy Goodman, versus Harry Elkes paced by a series of seven man-powered tandem teams. The event was billed as man against machine. Unfortunately, the drive belt on Fournier’s machine parted during the third mile and took him out of the race. Oscar Hedstrom was present and competed in the professional half-mile race (placed 1st) and the one-mile handicap (placed 2nd): it’s hard to imagine that he missed seeing Fournier’s pacer perform.

In March of 1899, Fournier built a motor tandem configured as a “bob tail.” Invented by Hedstrom the previous year, the frame design positioned the rear seat placed behind the axle to provide the racing bicyclist with a better slipstream; it would become an extremely popular pacer style. In May, Fournier began to import tandem motor pacers from France and first used them at Ambrose Park in Brooklyn. Demand was high and that month the Fournier-Henshaw team also appeared at the Woodside track in Philadelphia and the Baltimore Colosseum. Although Charles Henshaw was involved with Fournier’s import business and pace team, he also organized his own professional motor-pacer teams and promoted races at Crystal Lake Park in Middletown, Connecticut.

The Waltham Manufacturing Co. was producing the popular Orient bicycle and developed an Orient motor pacer using an Aster engine. It was finished in time for a race meet on May 30, 1899, and early in June, Henshaw was riding it at the Waltham and Charles River tracks. On June 17 at the Waltham racetrack, Fournier and Henshaw riding a French pacer were beaten by the Orient machine. The same happened at the Manhattan Beach track on July 4, except this time Henshaw and Fred Kent partnered on the Orient. By the fall of 1899, the Orient pacers (not retail motor bicycles) were being advertised for sale—25 sold by the end of the year—and almost no champion bicyclist now was willing to compete without a motor cycle pacing him.

The evolution of and demand for motorized pacers was explosive. Promoters wanted them because they were less expensive than paying multiple teams of human pacers and their novelty drew crowds. Racers wanted them because they attained faster times and thereby were able to establish new track records. In an October article in The Wheel & Cycling Review it was revealed that Frank Waller made $1,000 clear in one month while operating a motor pacer and that another champion racer made enough money to purchase a second machine after only a month of operating his first. Also, in one month during 1899, Fournier and Henshaw had 16 pace engagements and traveled over 10,000 miles to fulfill them. There was money to be made.

During this period, both Oscar Hedstrom and Charles Henshaw were also racing as professional bicyclists and, as a muscle-powered tandem team, held the national records for the unpaced half-mile and mile, and the mile and two-mile records for paced. As part of a quint (five-man tandem) team Hedstrom placed third at Ambrose Park in May, while Henshaw, paired with Kent, came in fourth. Unfortunately, on June 19th at Manhattan Beach in the fourth lap of the Great Atlantic Sweepstakes, Hedstom got tangled up in a spill with two other riders and dislocated his shoulder, which put him out of competition for the remainder of the season.

In September 18, Hedstrom teamed up with pattern designer William Russell Frisbie, who did contract work for Worcester Cycle Mfg., Waltham Mfg., and Keating Wheel Co., to create a motorized pacer. Hedstrom built a tandem frame and modified—or, at the very least, converted from metric to SAE—a De Dion engine in the shop that he had been renting from Worcester Cycle since February 1898. This tandem motor pacer, nicknamed the Royal Blue Express because of its paint and nickel fixtures, was built under contract for racing star Charles Miller. Weighing only 130 lbs., it was tested on November 24, 1899, in Middletown and three days later at the Berkley Oval in New York. It would be used in the main event at Madison Square Garden on December 16 to successfully pace Harry Elkes in the one-hour race.

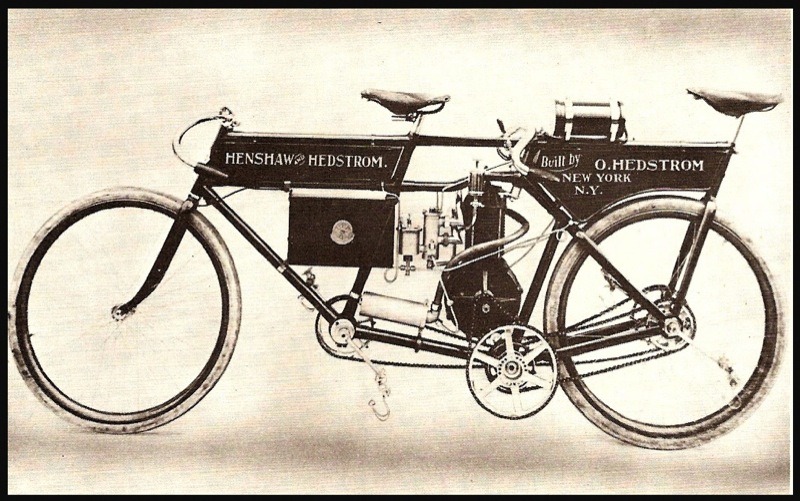

The partnership between Hedstrom and Frisbee was dissolved in January 1900 because Frisbie wanted to develop marine engines and automobiles. Hedstrom continued working on his own motorized pacers fitted with his modified De Dion “Typhoon” engines—tandem #2 was built in May with a 3.25 hp engine and #3 had a 5 hp—and producing his Hedstrom Special racing bicycles. Several of the motor tandems were sold to racers in the spring, but despite numerous requests he stopped producing them during the race season due to team commitments.

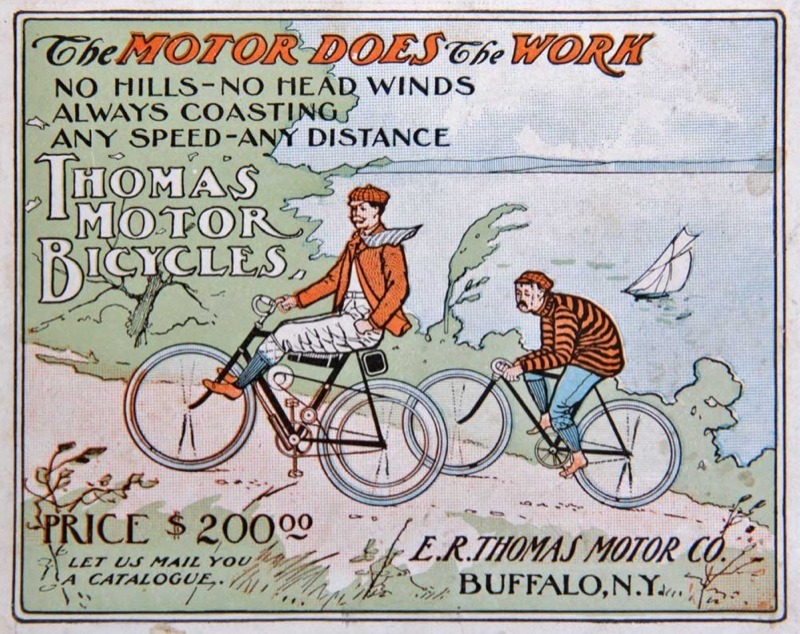

That March, Kenneth Skinner retained the services of both Henshaw and Hedstrom as racing experts to represent his interests on the track, but it wasn’t an exclusive contract. The team of Henshaw and Hedstrom owned two Typhoon tandems and ran them with Everitt Ryand and Harry E. Caldwell—both champions—as steersmen during the 1900 race season, and there was the team of Fournier and Henshaw with its own hectic schedule. Although Hedstrom and Henshaw did pace in the Springfield event on July 31, the press mentioned one or the other men at numerous events from Philadelphia to Boston during the 1900 race season. The 15-mile motor tandem race that was held on December 28 at Madison Square Garden has provided a basis for one version of the Hendee-meets-Hedstrom myth, but whether or not either man attended that event remains unknown. However, that month it was announced that Charles Henshaw would be going on the road as the New England representative for the E.R. Thomas Motor Company. This, plus the Worcester Cycle Co. bankruptcy, may have had an impact on Hedstrom’s decision to seek another venture.

Check out The Early History of Indian Part 1 and The Early History of Indian Part 3 for more of the story.

[…] out The Early History of Indian Part 2 and The Early History of Indian Part 3 for more of the […]

[…] out The Early History of Indian Part 1 and The Early History of Indian Part 2 for more of the […]