The rules for the AMA’s Class C Production racing class since 1933 worked well to balance power from different engine configurations. Flathead designs were allowed up to 750cc, while overhead-valve machines were limited to 500cc.

But by the 1960s, the side-valve/flathead engine was antiquated. No one made flatheads besides Harley-Davidson, and the design simply had no future. Meanwhile, new engine designs were emerging that drastically elevated the levels of competition.

In 1966, the AMA competition committee voted to change the rules for the 1969 race season, limiting displacement to just 350cc and transmissions to five gears, with a minimum of 100 bikes available for sale in the U.S. Harley responded with a development program with Aermacchi in Italy for a 350cc Sprint in roadrace and dirt versions.

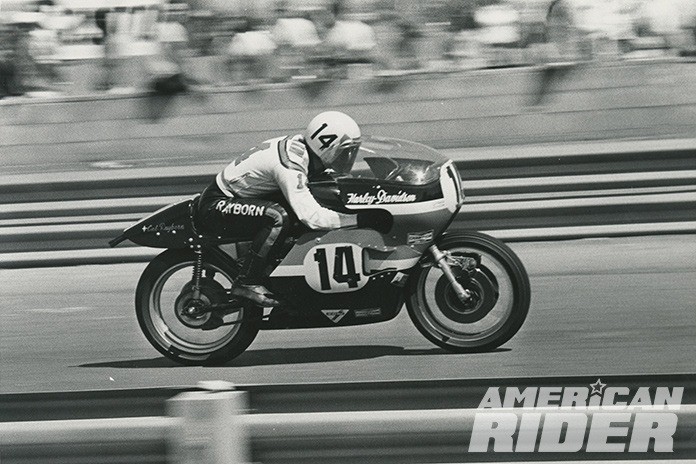

In 1968 at Daytona, the legendary Cal Rayborn put Harley’s KRTT on top of the box, but a pair of nimble 350cc Yamahas on the podium with the KR brightly signaled a changing of the guard.

Rod Coates of Triumph and Wally Brown of BSA left Daytona depressed. Their 500s couldn’t beat the 350cc Yamahas, so they realized their 350s wouldn’t stand a chance. They went to the AMA Competition Congress in October 1968 and proposed new rules for OHV motors, increasing displacement to 650cc. Harley didn’t have an engine that could be made into a 650, so it offered a counterproposal for a 750cc limit that was adopted for the 1969 dirt-track season, a formula that was followed for the 1970 roadracing season.

Harley’s pragmatic race boss Dick O’Brien selected the only OHV V-Twin racebike Harley had in its arsenal, the 883cc XLRTT. It was a racing version of the Ironhead Sportster that fit the AMA Tourist Trophy (TT) specification, which had a 900cc displacement limit. Shorten the stroke 0.6 inch, and you’ve got a 750cc racer.

In February 1969, Harley submitted brochures, photographs, and specs for its new racebike, which was basically a KRTT but with an Iron XR750 motor. It wouldn’t make its race debut until the following year. Revised rules mandated 200 bikes of a particular model to be built, despite William Harley’s letter to the AMA asking for no minimum requirement of production.

Meanwhile, at Daytona in 1969, Rayborn took the long-in-the-tooth KRTT to its final victory at the speedway, finishing ahead of Suzuki-mounted Ron Grant and Canadian Mike Duff on Yamaha’s 350cc 2-stroke Twin.

The Ironhead XRTT

Harley’s new beast for 1970 featured bigger valves stuffed into trick heads (machined by legendary tuner Bill Werner at the Harley race department) and actuated with Sifton A cams and special pushrods. Race-spec flywheels, rods, and Offenhauser pistons were lubricated with a quarter-speed oil pump. Ignition was by a Fairbanks Morse magneto in front. Power was sent via a dry clutch to a close-ratio 4-speed transmission.

At the introduction of the roadracer in February 1970, it was announced that the new XRTT produced just 62 hp. O’Brien was known to be cagey, so everyone thought the rating was low. It wasn’t.

The first problem was the XR’s iron heads and cylinders couldn’t shed heat fast enough from the wide-open running required of a roadracer. The second problem was with oiling – as in too much of it, causing drag on the flywheels and parasitic loss of power at high revs.

When the factory team showed up for Daytona in 1970, the XRTTs sported two Tillotson carbs on individual manifolds to help it breathe at high revs, as well as other evolutionary upgrades. This was more of a Band-Aid than a cure – the 80-hp Triumphs qualified at 157 mph, while the XRTT, at 150 mph, was no faster than the old flatheads.

In the 1970 race, all four factory MoCo entries retired with melted pistons, giving the win to a Honda 750 Four ridden by Dick Mann, with Triumph 750cc Triples in second and third. There were more failures for Harley during the rest of the roadraces in 1970, with a long list of issues that collectively prevented the Iron XRs from getting near a winner’s circle.

The postmortems after this dismal season revealed that frail pistons and poor ring sealing were part of the puzzle. Traditional built-up cranks using pressed shafts and a tapered crankpin failed at speed. Running in ball bearings, they needed to be inflexible and perfectly aligned, and they needed to stay that way.

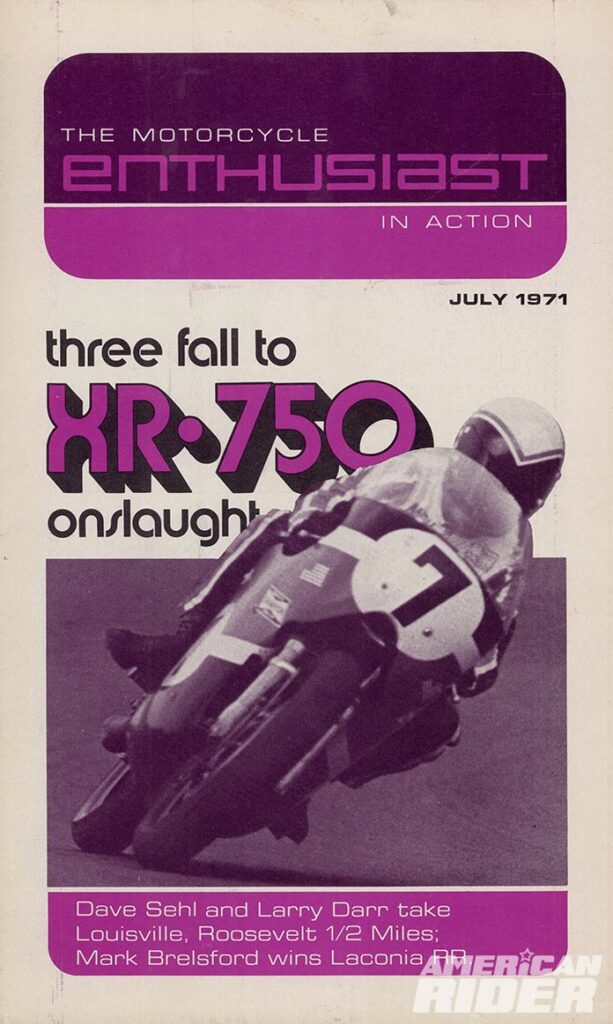

Despite the massive effort to improve what had become known as the “Waffle Iron,” the 1971 season wasn’t much better for the XRTT. Hopes were high when the Harleys of Cal Rayborn and Mark Brelsford were gridded up at Daytona in second and third positions behind Paul Smart in pole position on a Triumph Triple. But those hopes were dashed when none of the MoCo’s finest finished the race. Instead, Dick Mann won for the second consecutive year, this time on a BSA, with Gene Romero on a Triumph in second and Don Emde on a BSA in third.

Later that season, Brelsford’s mastery of Loudon’s slower, twistier track gave the XRTT its only victory. By then the Waffle Iron had oil coolers and its fourth version of the cylinder heads. It went like this:

- First version – Stock XLRTT arrangement with hemispherical combustion chambers and a single carb

- Second version – Modded for dual carbs on individual manifolds in the center of the vee, XR750-style

- Third version – Developed by Mert Lawwill, Jim Belland, Cal Rayborn, and Leonard Andress for dirt-track use, with the front intake and exhaust in the stock locations but the intake for the rear head moved to the left front; the front carb was pointed to the right rear

- Fourth version – Two front heads with individual carbs affixed to the right rear of each (like the aluminum XR)

It took Bill Werner and a helper six months to fill, braze, weld, trim, and shape these heads. All subsequent versions of XLR heads used on the XRTT had different porting and combustion chamber shapes as well. Not only was it an incredible level of reworking for a few horsepower, it also seriously bent the rules restricting use to the manufacturer’s heads, cylinders, and crankcases as approved “production” parts.

In the last two versions, the only thing production about them was the base castings. O’Brien said years later they never would have gotten away with these head mods if H-D was a threat. By then, the Iron XRTT was more reliable and made 68 hp. It was better but never great.

The time came for the second prong in O’Brien’s approach: his “real” racer. The era of the Iron XR was ending, and the aluminum XR was just beginning.

The Aluminum Age

Introduced 50 years ago, the aluminum XR is now revered as the most successful dirt-tracker ever made. The roadracing version, the XRTT, is another matter entirely. Designed by O’Brien and Matt Kroll, the alloy engine was ready by early 1972 but not soon enough to build the required 200 examples in time for Daytona.

There were key changes in the new engine aside from the obvious aluminum top end. The bore and stroke were changed from the previous 3.00 x 3.18 inches to 3.125 x 2.98 inches, and the connecting rod’s thrust and angularity issues were solved by new shorter rods.

The flywheels were forged in one piece and no longer held together with lock nuts on the crankpin. Instead, they were hydraulically pressed together and then welded, which made for a far stronger crankshaft. The timed breather stayed in use, although versions were tried without it.

XRs built for 1972 were fitted with so-called “super blend” bearings, which have barrel-shaped rollers that allow for crank flex and were used in the 1967 Triumph 500 that won Daytona. The rods were changed to a more optimal length to avoid issues with angularity and thrust. It helped, but ultimately, the cranks had to be precision-welded to endure high engine speeds.

The alloy XR engine could breathe better, rev higher, and – most importantly – stay cool. The changes were terrific for American dirt racing but short of competitive for roadracing.

The 1972 season began with spectacular performances from Cal Rayborn at the TransAtlantic Match Races, a six-race series of three doubleheader events in England. It was Cal’s first trip overseas, and he was faced with racing on technical tracks he’d never seen on an Iron XRTT tuned by Walt Faulk of the race department.

Incredibly, Rayborn won half the races of the series, and he would’ve won a fourth if his tired Harley didn’t lose power during the last few laps of the final race. The likable and talented Rayborn tied for wins with ace Brit racer Ray Pickrell on a BSA Triple, providing a morale boost and great publicity for the MoCo.

“When it was all over,” said Jim Greening about Rayborn in Cycle, “they could have given him Buckingham Palace, and nobody would have minded.”

Although the XRTT was successful overseas, it was a marginally competitive racer with teething problems during the American season. The factory barely placed in most of the roadraces that year. One bright spot was when Rayborn won the Laguna Seca round by using less fuel than the Kawasaki and saving an extra pit stop, as well as employing a front disc brake.

The simple fact is, between the modern 4-stroke multis and the awe-inspiring 2-strokes from around the globe, the sole Yankee V-Twin was overmatched at every turn. By the end of 1972, the XRTT was pulling a respectable 83 hp on the company dyno, but the competition had closer to 100 horses, sometimes more. Even the Yamaha 350cc Twins had better power-to-weight ratios. Rivals had 5-speed transmissions, but the XRTT had just four cogs.

In addition to the XRTT’s horsepower deficit, there were also handling and braking issues to sort out. Old-time racers were sometimes wary of disc brakes, so most racebikes of the era, including Harley’s, used 4-shoe drums in front instead of the disc brakes that would soon take over. Frames for the XRTT were built by Nichels Engineering of Griffith, Indiana. The design was good but nowhere near cutting edge. The alloy XRTT needed more urge even though its engine was 17 lb lighter.

Don Emde, winner at Daytona in 1972 on a Yamaha 350, had a stint campaigning an XRTT in England and Australia that same year. The brutish Harley was a completely different animal than the smaller and more maneuverable little Yamaha.

“I didn’t sit on it right the way it was set up, so I didn’t instantly take to it,” Emde told us, adding that he hated its bulky fairing. “It was so different than the Yamahas that I never did well on it.”

Hindsight is always 20/20. Harley’s progress with pavement racers was incremental while the competition’s was exponential.

As if to underscore the point, 1973 was the worst roadracing season in the MoCo’s long competition history. It began with disaster at Daytona. Affable Mark Brelsford, the 1972 AMA champion, was charging through the infield when he hit another rider’s broken and coasting machine. Brelsford’s XRTT burst into a ball of flames with him still aboard. He was thrown clear but suffered extensive injuries and was done for the season.

Rayborn suffered a litany of issues and came up with zero wins for the season, and there were no podium finishes for the XRTT. Then came the tragedy of Rayborn’s death in an unimportant race on an unfamiliar Suzuki in far-off Australia, ending a sad year and the life of a legend.

The salt in Harley-Davidson’s wounds came when the AMA announced rules for the 1975 season. The need to build 200 production machines to race was dropped. Instead, only 25 were required – lowered again one year later to just one complete motorcycle plus 24 engines. The new rule killed any hope of a roadracing future for the XR engine. Meanwhile, Yamaha’s 2-stroke, 4-cylinder TZ700/750 platform was a game-changer, making everything else obsolete.

“They were three to five years too late with the alloy XRTT,” Emde observed. “And there was no way they were going to run with TZ750s.”

The only upbeat adjunct to the demise of the MoCo’s domestic roadracing was the company’s European division. Aermacchi was on the verge of winning several roadracing world championships with Italian-built 2-strokes (see American Rider, August 2022).

(Sources: Harley-Davidson XR750: Allan Girdler; Bill Milburn; Bill Werner, National Motorcycle Museum; Cycle World; Harley-Davidson Motor Co.; Mecum; Cycle)