This year marks the 100th anniversary of something more life changing than damn near anything you can name. Normally, an innovation of this earth-changing magnitude would bring on an unqualified whoop and holler… freakin’ great news, if ever there was. But for motorcycle fans it was (and to some degree remains) a near-death experience, although most don’t give it a passing thought.

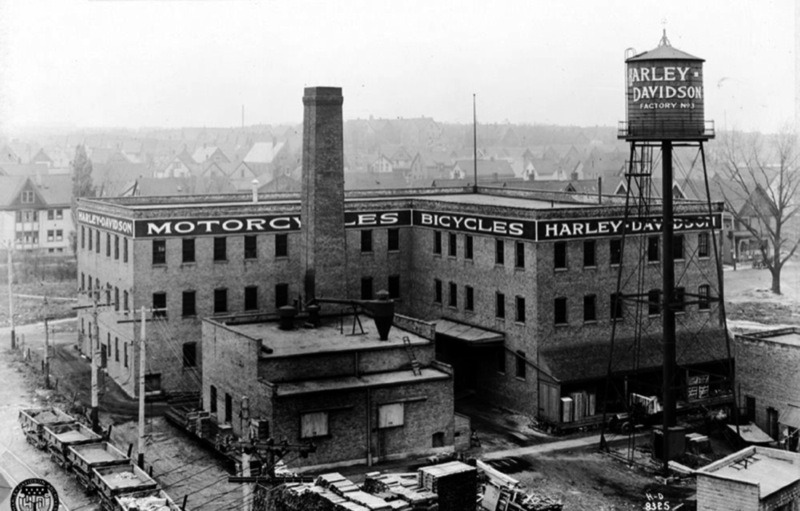

Caption: Harley-Davidson began construction on this in 1912. A far cry from the humble “shack of 1903” legend. Still, conservative as ever, it was not paid for with borrowed money and notably was built of everlasting brick. A nice, if not overwhelming, facility from which to inch-by-inch generate enough sales in the face of ever-changing times and technologies… to survive!

You see, in 1913 Henry Ford got the first moving assembly line in history going at his spanking new Highland Park plant. (Please do not confuse mass production with a moving assembly line!) Mass production had already been around for a long time when Henry, his production chief, Charles Sorenson, and a whole host of unsung heroes sought to figure out a more efficient way to build Model T cars. They thought their way through reversing processes of the Chicago meat packing industry’s “disassembly” line for taking a carcass apart in the most efficient manner possible. Turns out that meant bringing the work to the worker. All mass production methods previously had done it the other way around, even the Armories… and the motorcycle industry. Up until then, and for centuries before, if you wanted to build more of anything, no matter how efficient you were you needed more people to do it. With the advent of breakthrough technologies such as interchangeable parts (among others), this had become quite the bottleneck to real volume production.

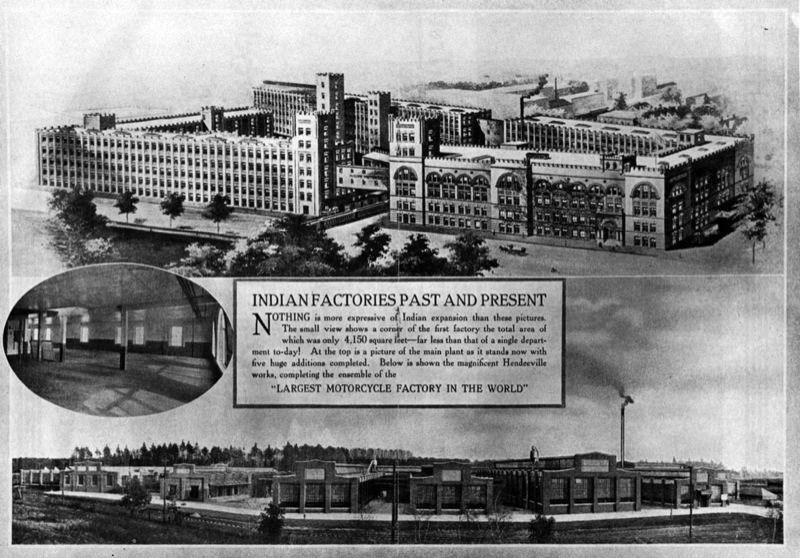

Caption: Indian, on the other hand, had gone public and used that cash to build their own new temple of motorcycle manufacture (shown above and forever to be known as the “wigwam”)… the largest and fanciest in the world. At the time, the company could not build enough bikes to meet demand and was counting on a trajectory based on past performance that would lead to production numbers in the six-figure range annually. Thanks largely to Henry Ford it never happened, and motorcycle production (and everything else they tried to make there) required less than 10 percent of the factory’s capacity.

Implementing a system that involved a series of moving sub-assembly lines on conveyor belts all around the new Highland Park building simply meant workers did not move to the product; the product came to them. Or at least their particular bit of it. Each worker was given a specific task to complete, which they would repeat every time a new portion of a car came to them along a conveyer belt. In turn, sub-assemblies were fed to the main line and installed on a moving chassis, kept in motion until the car was complete—reducing the time to completely assemble the vehicle from several hours per car to a few minutes, thus handily increasing the number of Model Ts Ford could make in a day to supply a seemingly insatiable demand around the world. It also had some unintended consequences, not the least of which was turnover at the factory! When you’re running though 190,000 people a year to keep 19,000 never-before-seen, boring, repetitive, man-killing jobs filled, it’s pretty counterproductive. Ford (and Henry Ford alone this time) muscled through the infamous “Five Dollar Day” to fix this and created a whole new level of American economic function that the establishment thought nuts, but that history applauds as the first time folks could afford to buy what they built. Never mind that this new concept meant the maturation and proliferation of “division of labor,” mostly by unskilled workers, and what we now call a higher standard of living. There’s also the mouthwatering reality of higher quality at a lower price, when volume explodes. The point is, by putting America on wheels with a new wrinkle in the industrial game, the moving assembly line created a whole other world… the one we live in!

Caption: Exactly why that might be gets a little more obvious when you couple efficiency (in the form of the moving assembly line) to capacity in the form of this spankin’ fresh Highland Park facility of Ford’s! Inside of a decade, Model T production would actually outgrow Highland Park, leading to construction of the largest factory in history–the River Rouge complex. Henry made his vision of raw materials coming in one end and cars rolling out the other a reality complete with his own ships, plantations and more! How could the bust in the motorcycle industry ever combat the boom in autos?

Car creator—bike killer!

The year the “T’ line was fired up in Dearborn, it resulted in over 170,000 new Ford cars. At the same time, Highland Park’s 19,000-plus employee roster alone would be enough people to buy roughly half of the total motorcycles made in the U.S. in 1913! For example: Indian, the largest manufacturer in the world, also had a new, million-square-foot, 12-acre, seven-mile circumference factory, employing 3,000 people and mass producing 32,000 motorcycles. It was the best they’d ever do, with a factory capable of producing 100,000 motorcycles a year even without the moving assembly line! Meanwhile, Harley was gaining on Indian in their equally new factory on Juneau Avenue, to the tune of more than 16,000 machines. Excelsior, the nation’s number three in an industry which suffered a 97-percent extinction rate in 20 years flat, accounted for perhaps 4,000–6,000 additional bikes in that seminal year. So, a little math and we see clearly that Ford alone (never mind the rest of a the burgeoning auto industry) was putting the screws to the domestic motorcycle builders at a rate of over 3:1.

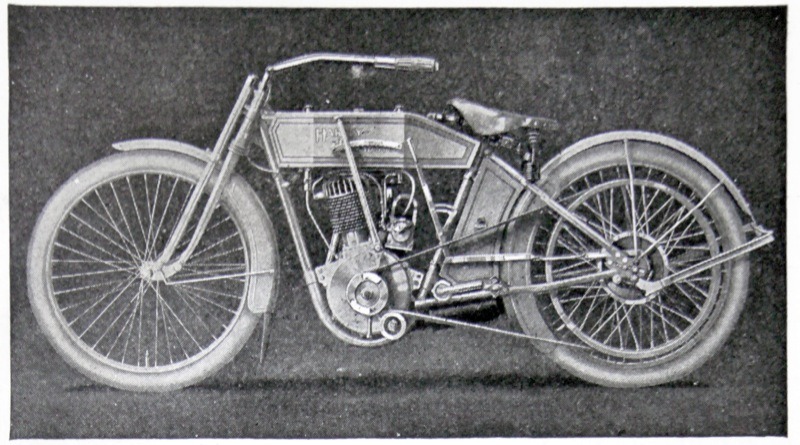

Caption: Innovation was the first method tried… by Indian! This 1913 model has chain drive, and a clutch, with available two-speed gearbox, not to mention rear suspension! A year later they one-upped with electric lights and starters on the so-called “Hendee Special.” Would’ve helped too, if it had worked—alas! Not for the first or last time battery technology of the time sunk a good idea that was ahead of its time. The company’s next move was patriotic but idiotic: They supplied their total production to the military during World War I, which seemed logical at the time to a firm hoping to actually utilize their factory. What came instead was pissed-off dealers, alienated customers and lost money. It also parked them firmly and permanently in second place behind Harley at war’s end.

Flash forward to the last decent year the motorcycle industry had after the Great War. Ford (a pacifist) had ramped up the ever-more-efficient moving assembly line (as had his competitors), managing to make over one million Model T cars in 1920. By then Harley had surpassed Indian and become the world’s largest manufacturer, building a nudge over 28,000 bikes to sell in 67 different countries. Adding Indian and Excelsior still leaves one agape with the gap! And it only got worse. There was a sharp recession (know anything about those?) in 1922 and the entire motorcycle industry eked out a meager 25,000 machines for the year. Match that against nearly 1.4 million Tin Lizzies, with GM about four years away from outselling Ford, and you can see that what the moving assembly line brought to the American motorcycle industry—regardless of what it brought to the rest of the country (and the world)—was devastation! By way of comparison, the entire population of the United States at the time was slightly over 183 million, and we had a total of 565,000 motorcycles, or three per 1,000 people. Britain’s population of fewer than 53 million folks had over 1.3 million motorcycles—10 times as many for every 1,000 of its citizens! We all know that Harley was the sole survivor of this automotive onslaught, but until AMF took over and finally added a moving assembly line to their defense arsenal, the pattern remained distressingly similar.

Caption: Harleys of the same era were still lookin’ pretty primitive yet endowed with tried and true features like belt drive, and just in case, single speed and pedals. Nothing flashy or innovative, but damn reliable and simple. That worked, along with incremental and ongoing improvement, to ensure both survival and growth over a decade filled with ever-increasing numbers of cars and ultimately only one crippled and struggling competitor. So in a way, H-D managed greatly by not doing anything poorly–with the exception of attempting to sell a small, sophisticated opposed-twin “gentleman’s” motorcycle in the early ’20s. That flopped (as did Indian’s attempts at the same notion) and the message was clear: There was no transportation market left in the U.S. Thanks to the moving assembly line, motorcycles would never again compete with cars for that customer. Instead, the few core converts that remained simply craved what Harley had to offer: a big, lusty, slightly anti-social machine that gave their fans a feeling, a freedom, and a social status cars could never hope to match! From then on, providing that one thing well (and going about it carefully) imprinted in Harley-Davidson DNA… where it resides to this day.

History repeats itself… or at least follows a pattern

When Henry Ford II retired from running his grandfather’s company 50-some years later, its production was over 6.5 million worldwide. Contrast that with The Motor Company’s paltry 47,700 American motorcycles, which was at the time (1976) Harley’s best year ever! Of course, by 1976 both the Model T and Harley Flatheads were gone forever, but the lessons remain and the methodology is both life changing and permanent… 100 years later.

Caption: The bane of bikers was a boon to most everyone else, and Model Ts were pouring out the factory doors at an astonishing and increasing rate for almost 20 years! Over 15 million Model Ts inundated the roads of America between 1908 and 1927. (Indeed, they were the reason the roads got built!) It amounted to an industrial tidal wave that all but sank the domestic motorcycle industry. Eerily, in this photo the moving assembly line is still. That’s OK, because it gives you a clear picture of the economy of scale that eventually made mass-produced cars cheaper (and more plentiful) than handcrafted motorcycles.