Funny where a casual observation might lead. I got myself a new H-D “picher” book for Xmas and it’s a real corker alright, with some of the most interesting and classy photos of the old iron in The Motor Company’s archives you ever saw. Heavy, too! You wouldn’t wanna drop this hummer on yer toes, I’ll tell ya. But, that’s not really the point. What happened was this: I keep the thing in the throne room and during my usual morning rites, happened to focus on the photo of the Harley “patent plate” gracing the springer forks featured so prominently on the dust jacket of this tome.

Now, I know there are those of you who already imagine that I don’t have a life, let alone anything better to do than browse the web on a whim, and know for sure that I’m so overly immersed in Harley lore and trivia that I’m comin’ out the other side. But—in my defense—I am a curious sort. So I really couldn’t help it, when I found myself doing a Google patent search for the 11 specific numbers listed on the plate. Wow!

I mean the patent plate itself is prob’ly worth a story (one I’ve never heard), since I know of no one who knows for sure where it came from, exactly when or why it was first used and/or how come it’s still stuck on springer forks, placed dead center on the front shock. A bit of a mystery to say the least!

What I can share with those who care is that Harley-Davidson has several hundred patents after all these years, right up to and including the one on the oiling system on V-Rods. They run the gamut, as there are patents and there are patents, after all. Some—the ones I like most—result from original thinking and creative problem solving, often leading to break-though technologies. Or, plain ol’ “way-cool” functional bits and pieces, comprising mechanical hardware we love to tinker with. Sort of the ultimate expression of new and improved—as it should be! The other kind of patent tends to revolve around the way things look, more than work. Could even amount to a particular noise, in case you recall H-D’s attempt to “own” the sound of the V-Twin engine.

One of the more notorious old patents around was the one granted in the late 1880s to one George Selden. Can you believe this guy had an enforceable patent on the automobile? It’s true! For nearly 20 years until Henry Ford hisself got it tossed, every car company in America had to pay a royalty to use the patent—even though George never built a working car of his own!

So with all this, and more, rattling around in what’s left of my mind, I couldn’t help but wonder why only these 11 particular patents—among the masses the company holds—merited being embossed on this prestigious plate and plastered in plain sight on the front end of Willie G’s pet fork design? (It’s on record that Mr. Davidson likes the springer largely because it’s the only fork on a hog that’s actually made in America, but could there be more to it than that?) The man is The Boss when it comes to Harley styling, after all, so maybe the decision to put the plate on the nose of that chrome front shock was strictly down to the way it looked (nostalgic and handsome), but I doubted it.

Let me just tell you what I came up with and maybe you can figure it out, OK? Hell, if nothing else, this’ll make great trivia for bar bets and other intellectual pursuits peculiar to bikers. And—even though they do not appear that way on the patent plate itself—let’s tackle them in numerical order.

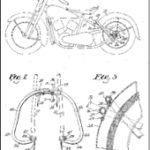

Patent #1834308

Yup, as you might have guessed, this is the patent on the springer fork filed in July 1929 by none other than William S. Harley and granted in December of 1931. The surprise is, this is not the patent for the original idea of a springer, but for an improvement in the strength and manufacture of same, by eliminating brazing it up in mild steel in favor of assembly of manufactured (forged) components. It’s interesting to me that this patent specifically relates to the non-tubular springer, which means it’s not all that similar to the one we have today, even if you don’t consider that there’s no shock at all on these old forks. It’s aptly named “springer,” but maybe spronger would be even closer to the truth.

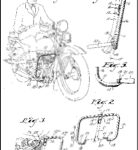

Patent #1941801

OK—here’s where the soup heats up! Bill Harley, back in January of 1934, patented what he referred to as a “motorcycle protecting guard.” Basically, boys and girls, the man invented what we used to call “crash bars” and are now (to be more politically correct) listed universally as engine guards. In this case, the patent was granted for a front one, but back then—was there even such a thing as a rear guard? Besides, what the heck does any of it have to do with springer forks and/or the patent plate?

Patent #1941801

OK—here’s where the soup heats up! Bill Harley, back in January of 1934, patented what he referred to as a “motorcycle protecting guard.” Basically, boys and girls, the man invented what we used to call “crash bars” and are now (to be more politically correct) listed universally as engine guards. In this case, the patent was granted for a front one, but back then—was there even such a thing as a rear guard? Besides, what the heck does any of it have to do with springer forks and/or the patent plate?

Patent #1961145

W.S. Harley “et al” (in the wording of this patent from 1934) have developed herein what would later be referred to in Harley literature as the “full-floteing” (sic) saddle. In plainer English, that means the seat of childhood memory and rigid framed touring bikes, with the two big “booster” springs on the sides and the sprung “post” that disappeared into a vertical frame tube right under yer arse. Hasn’t been used since the Shovelhead era really, but who cares? The “bottom” line in its day, it’s unique and neat beyond description! And who can figure why this item made it onto the patent plate?

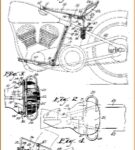

Patent #2091682

There’s no way that Harley—the company or the man—can claim to be the first to mount the speedometer on the gas tank, since that was originally done about three weeks after motorcycles were invented. However, to put that essential gauge, the equally essential ignition switch, and for that matter all the other information an ammeter or oil pressure gauge can offer in addition—all in one incredibly gorgeous chrome housing—was a stroke of brilliance! It was good enough as a concept to last right up until today in various styles, not the least of which is a 21st century update of that original “cats-eye dash.” Are you seeing any common connections to the patent plate yet?

Patent #2109315

Sometimes, when you’re looking north something totally unexpected sneaks up on you from the south. I’m highly suspicious that this is exactly the case here. I mean it may have started out as a good idea for a set of boxes to hold the bulky tube-type radio equipment that the cops started to use in the ’30s, but it looks a lot like a small set of hard saddlebags to me. It’s complete with a frame-mounted bracket system that allowed a much higher weight carrying capacity and more stable, smoother mounting for those delicate radios than soft leather throw-overs could ever manage. Could this design, patented for a whole other purpose in 1938, possibly be the forerunner of those hard bags you got hangin’ on the bagger in your garage right now? Could be—whether ol’ W.S. saw it coming or not.

Patent #2109316

Like most of the other items listed on the patent plate, this one was already in use by 1936 while the patent was applied for. Years later, in ’38, it was granted to this “oil tank and battery assembly” Bill Harley would probably never have called a “wrap around” or “horseshoe oil bag.” Yet, also like the other goodies we’ve grown to associate with Harley-Davidson motorcycles (if not the patent plate), descendants of this timeless design still adorn Softails to this day!

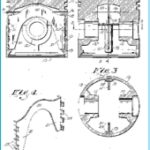

Patent #2111242

Owners of Twin Cam Big Twins might not appreciate this one, but the guys that designed that powerplant in the late 1990s sure do. In fact, they’d be the first ones to tell you that this 1938 patent for a “lubricating system for internal combustion engines” was the hardest thing to improve on, when it came time to move beyond the single-cam Big Twins. All of them owed their design heritage to the Knucklehead—and the essentially right on, non-computer designed—engine oiling system designed by Bill and the boys 70-odd years back. The heart of the concept dealt with the massive huffing and puffing going on the crankcases of the “only four-stroke motorcycle with two stroke cases.” It took awhile to determine that alternating pressure and vacuum inside the engine caused all kinds of weird reactions in the lubrication process. The key to solving that problem was a rotating, timed “breather” that allowed air to get the hell out of the way of the oil, in the right amounts, at the right time. Seven decades later, this patented solution remains a tough act to follow.

Patent #2126752

Speaking of following, it follows as night the day that the folks who invented the crash—er—engine guard, for the front would come up with a companion piece for the rear and here it is. Circa 1938, a dandy “bracing guard” from “assignors” (like Bill Harley) for The Motor Company, named Harry A. Devine and Frank M. Melitor.

Patent #2180521

Until the advent of cam-ground, barrel-shaped Mahle pistons in the 1984 Evolution engine, the next best thing for over 50 years was the type of piston with which this particular patent deals. It amounts to an alloy piston with a cast-in steel “bridge” insert to keep its shape slightly oval when hot. The principle is to keep the fore and aft thrust faces as closely matched to the cylinder as possible, while leaving a little room on the sides for expansion—thus curtailing any tendency for said alloy piston to seize to its iron barrel. All this rocket science when metallurgy was still close to alchemy—1939.

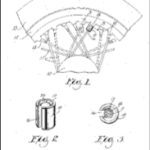

Patent #2269670

It’s a small thing, really—literally a wheel weight of mere ounces. But in 1942, Ed Kieckbusch was onto something big with his little idea. Not only was it a better-looking gizmo than had previously been seen, it locked on and lived in the centerline of the wheel and chassis, stabilizing steering and handling. It was in a very real way a great enabler. Consider that tires—let alone steel rims and spokes—of the day were more often than not horribly out of balance in their natural state. To go 70 or 80 mph was literally taking your life in your hands. Freeways and resulting opportunities to go way faster than ever before were looming large in the then-near future. Add the fact that there was a horsepower increase almost every year. It becomes very clear that a little wheel weight, properly designed, installed, and balanced, made an enormous difference in safety and smoothness when motorcycles were running closer than ever to the magic “ton” (100 mph) and you might appreciate why the seemingly lowly wheel weight makes Harley’s short list of great patents. All of which led more or less directly to the machines we love (and recognize at a glance) even today.