Touring Minnesota’s Ancient North Shore

If you go when the snowflakes storm

When the rivers freeze and summer ends

Please see if she’s wearing a coat so warm

To keep her from the howlin’ winds

—Bon Dylan, Girl from the North Country

I had forgotten about that feeling of violence that rises up through the ancient volcanic rock of Minnesota’s North Shore, where Highway 61 carves a thin rivulet of asphalt against a dead mountain range and down in the black, predawn water, waves wet the rough pebbled beach and tall boulders.

The water was cold. The air was colder but there was no frost. Cars with bright lights and loud trucks carrying lumber went by and down the road, carving a path through darkness on the way to the Canadian border. And all I could think about was Bob Dylan’s youth, violence and the warm soft bed my wife and I had left, leaving the smell of coffee beginning to brew, and how it had been over 10 years since I had looked clear to the horizon over Lake Superior.

My wife was huddled, bundled tight, hiding from the wind in a wave-carved basalt pocket. Besides a flashlight and the drags from my Newport, it was completely dark.

Then the sun rose purple, red, and finally yellow and the lake was blue again, the water was clear and the trees back behind the lodge that climbed to the top of the mountain, were burning brightly.

“It is hard to believe this place is real,” she said.

We went back to our room at the Cascade Lodge and drank black coffee and slept for an hour, had more coffee in bed before getting fresh and hitting the road, riding north in tune to a playlist of Neil Young, Wilco, Andrew Bird and Radiohead.

It was the third day of a four-day motorcycle trip along Lake Superior to capture the peak autumnal colors before the depressing Minnesotan winter took hold. And it was our first long ride together in many years. We started from St. Paul Harley-Davidson, riding a Vivid Black 2019 Ultra Limited—a god damn beast of a machine in both weight and power; a 900lb workhorse designed for regal riding; a Lincoln, a Cadillac, a Range Rover … it turned heads and with a 114 c.i. Milwaukee-Eight engine and chewed up miles without hesitation.

We had checked into the historic Cascade Lodge located between Lutsen and Grand Marais—a ski resort and a bohemian art enclave, respectively—shortly before dark the night before after a comfortable 100-mile brisk ride from Duluth. The Cascade Lodge was first opened in 1927 to serve affluent Duluthians and wealthy socialites. Commercial fishermen had already put the North Shore on the tourist map during the middle of the 19th century. By the turn of the century, Duluth reportedly was host to the most millionaires per capita in the world. Profiting from forestry, mining and trade along the Great Lakes, some had predicted that Duluth was destined to rival Chicago. F. Scott Fitzgerald, a Minnesota native, would have fit in well there, and drank well, too.

While the original Cascade Lodge was razed to the ground in the early ’30s, according to current steward Thom McAleer, who has been running the joint since 2017 with his wife, “it was not for insurance reasons, as people say. It was to clear the land to build a bigger lodge.”

McAleer said business was good year-round and that motorcyclists frequent the lodge regularly in the summer, while snowmobilers come in the winter. He and his wife are raising his two kids along the North Shore.

The geology of Lake Superior has always fascinated me. And it is a history of violence that can still be felt today. Long before human barnacles—from the ghostly-white Scandinavians to the soiled French fur trappers on down to the spirits that guided the Ojibwe—carved out life on this rocky, inhospitable shore, billions of years of primeval and powerful forces created, shaped and finally sculpted what we see today: the world’s largest freshwater lake that has claimed at least 550 ships in recent history, including the Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank in 1975.

As we rode into Grand Marais, French for Big Swamp, we followed the advice we received the day prior from Andy Goldfine, founder of the legendary riding apparel company Aerostitch, and looked out, hoping to see a congregation of seagulls darting at a skiff loaded with fresh herring.

“If you sneak behind the Angry Trout restaurant, you can still find fisherman cutting up the days catch, and freeze packing them to be sent to a Rabbi in Chicago to make them kosher,” Goldfine told us.

When we first met Goldfine the day before at his factory in west Duluth, we were greeted by a short, thoughtful, balding and bespectacled man. Andy and I commiserated over our time at the University of Duluth, albeit decades apart. Him with his philosophy major and English minor, and I with the exact opposite.

“I don’t really recall the thinkers I read. It was a long time ago and plus philosophy isn’t one of those subjects you can just bullshit,” he said, adding that it was one he could handle without needing to study too much.

“Well at least we are not waiting tables,” I said, using a longstanding college town insult about the uselessness of degrees in the arts. “Or majored in psychology.”

As we spoke about technology and its effects on society (both good and bad), how JFK versus Nixon was the first televised presidential debate, the absurdity of the global fashion industry as satirized in the movie Zoolander, motorcycling trends, the history of Duluth’s post-WWII economy, global trade, and how America has become a consumerism-driven throw-away society, it became clear that Andy was not just an inventor, but a sage. When his beautiful wife briefly interrupted us, I turned to my wife and said, “This dude is the shit!”

“Right?!” she said.

Andy opened his business in 1983. At the time, Duluth was in an economic recession and on the verge of becoming just another Midwest rustbelt town. U.S. Steel closed its coke plant in 1979 and a decade prior the Air Force Base that housed the 11th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron—a secretive Cold War defense outpost that housed 2,500 to 3,500 servicemen tasked with aircrafts that would be deployed following a Soviet invasion—closed.

When I was living in Duluth 15 years ago, west Duluth was rundown and largely abandoned. Now, tourism, college kids with bar money and gentrification has revived the area, with craftspeople, brewers and restaurateurs operating clean, modern industrial shops like what you find in Brooklyn.

Andy had seen all those changes to this old historic part of town. But what hasn’t changed is his philosophy to the iconic one-piece Roadmaster suits he crafts, which have been an integral part of the riding community for decades.

“Our customers are everyday riders because Aerostitch makes equipment. Just like a farmer’s overalls, carpenter pants, a lawyer’s or banker’s suit, it is the equipment that these professions invest in, not fashion,” Andy said. “Why are Levi 501’s and Chanel No.5 still the same? Because it is the recipe that works and people keep coming back.”

“Our logic is that our products are sacrificial. It keeps you safe from the elements and say you crash going 60 and you are okay, it did its job,” he added.

We toured his factory, met with his tailors and checked out his waterproofing testing equipment and impact armor fabrication set-up.

When we left, he wished us a happy marriage and I felt as if I had learned something.

Forgoing a lunch at Angry Trout as no seagulls were in sight, we went to the pleasant hole-in-the-wall South of the Border Café, an affordable classically designed American diner known for its burgers. The aged and old crowd enjoyed their simple breakfast while engaging in small-town gossip. The burger was plain and delicious. “Straightforward, always consistent,” one online reviewer wrote. Andy was right. Don’t mess with a good recipe. Outside of the restaurant, we got compliments about the Ultra Limited. Lying, I said it was mine, and told them to pay a visit to St. Paul H-D next time they are down in the cities.

After that we went north and then northwest, 15 or so miles up the beautiful Gunflint Trail that terminates at the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and Wilderness—a 150-mile stretch of hard-to-reach pristine lakes along the U.S./Canada border that skirts the Laurentian Divide, which separates water flow from either going down to the Gulf of Mexico or up to Hudson Bay.

Two billion years ago there formed a relatively small iron formation that stretched from Gunflint into Ontario. Starting in the 1600s, voyageurs would make a special stop here to collect flint from chert deposits for their rifles.

A loaded lumber truck with two blown out wheels partially blocked our path up the Gunflint, so we turned around and slid quickly back to the lake, testing the Ultra Limited at questionable speeds as the burning fall trees blurred into bright pastels and that massive tranquil lake from a distance, hid the violence of the land.

“The Lake Superior Basin, and therefore Lake Superior, sit dead center over an ancient rift valley, on not unlike the East African Rift Valley of today. The rift was active 1.1 billion years ago when Minnesota was really the center of the North American continent,” wrote geologist Ron Morton in his 2011 book A Road Guide: The North Shore of Lake Superior on Highway 61.

“Hot molten magma rose upward from deep within the earth, and as it approached the surface, it caused the crust to arch or bow upward, and then split like an overcooked sausage,” he added. A heavy pancake of basalt lava spread some two to ten miles deep across the region, with larger eruptions piling pyroclastic rocks around the edges of what today is the rugged Lake Superior shoreline. When the volcanic activity stopped, the weight started to sink the earth like a sponge.

But before that, a long time before that, to the west of the basin, a massive mountain range had formed, believed to dwarf the Alps and the Rocky Mountains.

With the aging mountain range shedding itself from rains and river flows, the sinking basin filled with sediment, creating a swampy plain. Then came the Ice Age, starting a mere 115,000 years ago. Glacial ice covered the land and pushing southward, violently scooping out the basin like an excavator.

The earth warmed, the glaciers melted and a lake was formed—the world’s largest in terms of area. Even to this day, the south and southwestern sides of lake are still springing up a few centimeters a year, gradually recovering from all the stress and raising the waterline on the Canadian side.

From Grand Marais, we drove up to the Lutsen Mountain Ski and Summer Resort, and for $24 apiece took the gondola up to the summit. That is where we caught the most impressive and wide views of the burning landscape. From a western outlook hundreds of feet above the valley floor, the trees where dead brown and red, a couple days past peak, while to the east, yellows, oranges and reds mingled with the green, winter-hardened, conifers.

We shared a bottle of Sawtooth Mountain Cider House’s Kim’s Blend cider with warm freshly made potato chips before heading out to track down a high school friend and nature photographer who was on his annual family pilgrimage to the North Shore.

“You might not want to hug me,” John Steitz said when we found him at the trailhead. “I have been hiking for four days now and I am pretty sour.”

I embraced him and so did my wife. I have respected Johnny for many years, but he smelt terrible, which killed my plan to give him a 100-mph wind bath. Johnny is a knower of all things worldly to the point of it being a detriment, replete with the wise beard not of a nicely combed motorcyclist, but of a hipster to the core.

From there, we went to our final sightseeing stop, Palisade Head. Palisade is a large rock formation with staggering 300-foot sheer cliffs with its feet buried in the sharp jagged rocks along the shore.

The three of us, along with Johnny’s older brother, scrambled and rambled to an outcropping, jumping a perilous gap in the rock to get the perfect shot.

Johnny asked if I still smoke weed. I said “no man. Not my thing no more.”

I told my wife and Johnny how in college we would all get stoned and drive up to this very spot, where the wind would whip so hard it felt as if it would blow you off the cliff edge. I hated being stoned here. The shaky knees, that animalistic urge that I would somehow just jump off the cliff and friends so scared that they would crawl slowly to the edge before retreating, holding onto the rocks as if they weren’t solid.

“I like it a lot better now,” I said. “Coming here back then, that is how I came to understand the violence of the North Shore, thanks to that psychoactive time machine. And I still feel it.” Everybody should feel it, I thought. It is humbling.

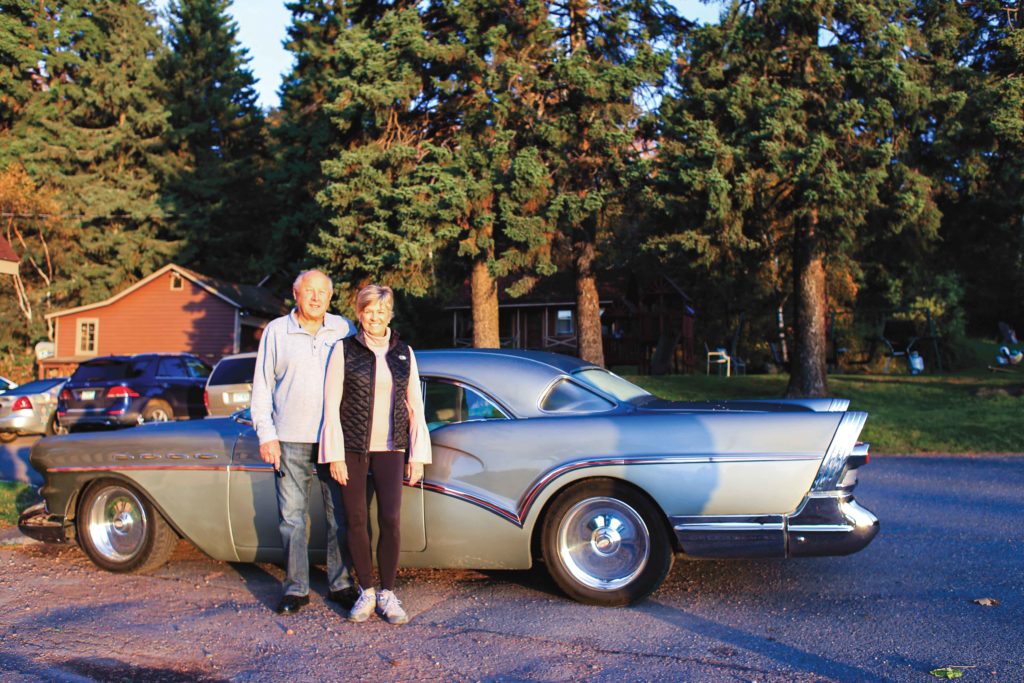

We left my friend and rode back toward the cities, taking the more scenic Wisconsin 35 highway. We stopped for dinner and a bonfire at a relative’s cabin. With clear skies and a chilly breeze, we slept with the window and door open, still wearing our clothes underneath the blankets.

The next day it rained cold, and I returned to St. Paul Harley-Davidson and told them thank you.

Special thanks to St. Paul Harley-Davidson for the bike loan.