Birth of the motorcycle

And its quick demise

It wasn’t just the illustration that caught my eye, it also was the date of the newspaper—1896. The front page of the December 12 issue of the Scientific American was devoted to two illustrations of a sophisticated two-wheeled vehicle that was identified as a “motor cycle using benzine.” My curiosity was piqued.

Joel Pennington had coined the word “motor cycle” in 1890, but the machine illustrated in the Scientific American seemed to be far more advanced than a motorized bicycle. The cross-section diagrams showed, and the text described in detail, mechanical features that would be considered innovative even for 1906.

This German motorcycle had a bent tube frame, footpegs, and both front and rear fenders for the pneumatic tires. The four-cycle engine was water-cooled with intake and exhaust controlled by poppet valves. Ball bearings were used on the cranks and rear axle. The front wheel had a brake actuated by a right handlebar lever (like we still use), and there was a throttle control on the right hand grip. The gas tank was located between the front downtubes of the frame, a water reservoir in the rear fender, and—Buell owners will love this—oil was stored in one of the downtubes. Remember, this was 1896.

Leafing through page after page in my library and employing a couple of Internet search engines, I was able to determine that this motorcycle was the 1893 invention of Alois Wolfmüller and Hans Geisenhof of Langsberg, and that it had been patented on January 20, 1894 (#78553). Historical details are sketchy, but apparently two brothers, Henry and Wilhelm Hildebrand, were producing bicycles in Munich and decided to develop a steam-powered velocipede (this is what bicycles used to be called) in 1889. When this didn’t work, they teamed up with Wolfmüller and Geisenhof, who created a four-stroke, 1498cc, two-cylinder engine that was fitted into the modified frame of the Hildebrand velocipede.

The cutaway diagrams in this article showed an engine and drive train that looked remarkably similar to that of a steam engine, while the overhead-valve system was shockingly modern and wouldn’t look out of place on an old Ford. Even at first glance it was obvious that this was the creation of experienced mechanics working at the cutting edge of internal combustion technology.

The team formed Motofahrrad-Fabrik Hildebrand & Wolfmüller in Munich, raised a couple million Deutschmarks through advanced sales, and commissioned architectural plans for an extensive factory on the Colosseum Strasse. Meanwhile, the manufacturing of parts was subcontracted to various firms and promotional efforts moved into high gear when they sent one of their motorcycles to a special exhibition in Paris in 1894 (probably the second Salon du Cycle that was held in December at the Palais de l’Industrie). The result was the licensing of a French company to produce La Petrolette. The following spring (May 1895), two H&W motorcycles entered the first Italian road trials, taking second and third behind a Daimler automobile. Success was within their grasp. Then came the first of the great European road rallies.

The Hildebrand & Wolfmüller motorcycle was an extremely advanced machine with an astounding top speed of 24 mph and could run up to 12 hours on a tank of fuel. It had a spoon-type front brake (much like today’s bicycles), the application of which simultaneously closed the throttle. The sophisticated rear water reservoir in the fender seems to have emulated Edward Bulter’s Petrol-Cycle of 1891, but the oil in the frame tube appears to be completely original. It was also the first motorcycle to use pneumatic tires (Dunlops). With a large horizontal cylinder on each side of the frame, it looked much like a steam engine with each drive/connecting rod linked to a spindle on the rear wheel. Instead of a flywheel, the H&W design used a solid 22″ rear wheel and elastic straps to assist with the return stroke of the pistons. Still, the H&W had some problems, and the most glaring of these was the hot-tube ignition system and what was required of the operator to start the engine.

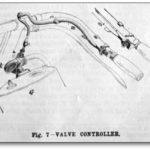

An excerpt of the Scientific American article details, “To start the motor cycle, the reservoir, G, is partly filled with benzine or gasoline; the door at the back of the ignition box is opened and the burner for heating the ignition tube is started by giving it a preliminary heating by means of an alcohol torch. As the door at the rear of the ignition box is opened for this purpose, the air supply pipe is closed automatically by means of a connection with the rear door. When the tubes are red hot the valve, H, is opened, the rubber bands are put under tension (more about that in a moment) and the machine is moved forward by the operator until an explosion occurs, when he mounts the machine and proceeds on his way. The proportion of the supply of air charged with petroleum vapor and pure air is regulated by the valve, H. By manipulating the cone on the lever, M, the supply of explosive mixture, and consequently, the speed of the machine, is regulated. When the machine is fairly under way, the tension of the rubber bands is released.

“Strong elastic bands are connected with the connecting rod and with an arm mounted on a rock shaft at the top of the cylinder. These elastic bands may be put under tension to assist in starting by means of a screw at the top of the frame, which is operated by a crank and miter gear.”

There was no clutch, and when the engine fired, the connecting rod was thrust rearward. Since there was no flywheel for the return impulse (once under way, the solid 22″ rear wheel provided impulse power), proper tension on the rubber bands was initially required to complete the drive cycle. The exhaust valves were actuated by long pushrods (the inlet valves were automatic) that were attached to cams on the rear wheel and, as the article explained, “the action of the exhaust mechanism controls the machine.”

Hildebrand & Wolfmüller had the only motorcycle on the market, and its future looked bright. A month after success in the 62-mile Italian road trials in Turin, two motorcycles were entered in the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris Rally of June 1895. By the midway point in this 732-mile race, the inherent problems with the hot-tube ignition and the erratic impulse of the rear wheel became obvious. From this point on things began to unravel as customers began complaining about problems—especially starting difficulties—and requesting their money back.

Gottlieb Daimler’s Reitwagen of 1885 was simply a test vehicle for his “grandfather clock” engine and Sylvester Roper’s steam velocipedes (1868–1892) were never intended to be other than experimental, so the Hildebrand & Wolfmüller bears the distinction of being the first production motorcycle. Despite its design problems the company had the mechanical expertise, and presumably the money, to solve these issues. The demise of the first production motorcycle came when it was discovered that the cost of manufacturing exceeded the selling price. Early in 1897, after making about 800 motorcycles, the German and French companies folded. Ironically, the birth of the motorcycle industry was about to begin.