Delving into the development of – and riding! – Indian’s all-new FTR1200 Street ’Tracker

Words by Mitch Boehm

Photos courtesy of Indian

If you’re a moto geek to any serious degree (and most of us are), real motorcycle development – and I’m talking about the stuff that happens in the R&D centers of big-time American, Asian and European moto manufacturers – is one of the world’s more interesting industrial processes. From initial concept, sketches and clay mockups to early and late prototypes, pre-production and final assembly, motorcycle R&D is a careful, behind-the-scenes process that melds stylists, engineers, designers and marketers, the end result of which a real, in-the-flesh motorcycle you can walk into your local dealership and actually buy.

It’s a fascinating process, and one I was fortunate to have been intensely involved in at American Honda for several years. Our R&D team took cruisers (Shadows), sport-tourers (ST1100, VFR750), sportbikes (CBR900RR, CBR600F2) and standards (Nighthawk 750) from sketch to production during that time – testing, talking and tweaking all the while. As exciting as it is (and riding a prototype can be really exciting, trust me), motorcycle development is a tricky business, with design and engineering obstacles and compromises that can be unexpected or unavoidable – or often both.

According to Indian FTR1200 design chief Rich Christoph, such was the case with the FTR – especially as the team worked to transform the look and feel of the knockout FTR1200 Custom show bike into a real production motorcycle during 2016 and ’17.

It wasn’t easy. Being a one-off prototype that had to look great and only perform well enough to not kill any engineers or media members who rode it, the Custom – and the folks who built it – had it somewhat easy. The emphasis was on aesthetics, not performance, durability or safety. They could concentrate on the visual, and largely ignore the engineering parameters a real street bike needs to stay within.

The production FTR1200? Not so much. It had to ride through a bazillion structural, engineering and DOT/homologation hoops, many of which made the transition from a styling prototype the world fell totally in love with to an actual production motorcycle quite difficult.

“The Custom prototype was just beautiful, and it hit the flat track-styling sweet spot,” Christoph said earlier this year. “But it could never be a production bike; you’d burn your leg on the exhaust, you’d run out of gas, the seat was carbon and hard, and who knows if the frame would endure all the wheelies that’d undoubtedly be done on it? But the street bike has almost all of the same lines, along with comfort, decent fuel capacity, real controls and mirrors, a taillight and all the DOT stuff that makes it saleable. The team did a great job!”

The ‘saleable’ element is key here, as the FTR is the first Indian intended to expand the company’s worldwide market beyond the cruiser, bagger and tourer categories. “We are forecasting strong growth for this market segment,” says Reid Wilson, Indian Motorcycle’s Sr. Director for Product and Marketing, “driven by the increasing relevance of flat track [racing] and the unmet need for globally competitive product from an American brand.”

The first FTR1200 prototype hit the road in January of 2017, just after the FTR750 racebike broke cover in late 2016. “We used this bike to prove out the concept from a technical perspective,” Indian told Thunder Press for this story. “The biggest things we took away were these: That it was a blast. A big V-twin in a sporty chassis worked really well. Also, the engineering mule was so good we couldn’t bear to go halfway – so we ended up going all-in with a new engine and a totally new ground-up chassis versus building from an existing platform.”

Riding impressions from the recent FTR1200 press introduction in Baja, Mexico, seem to back up those opinions. “For those accustomed to the low-seat, feet-forward riding position on cruisers like the Indian Scout, the FTR is very different,” wrote Greg Drevenstedt, Senior Editor for Thunder Press sister publication Rider magazine. “With its high seat and mid-mount pegs, the rider sits on top of the bike rather than down in it, leaned forward in an aggressive stance.

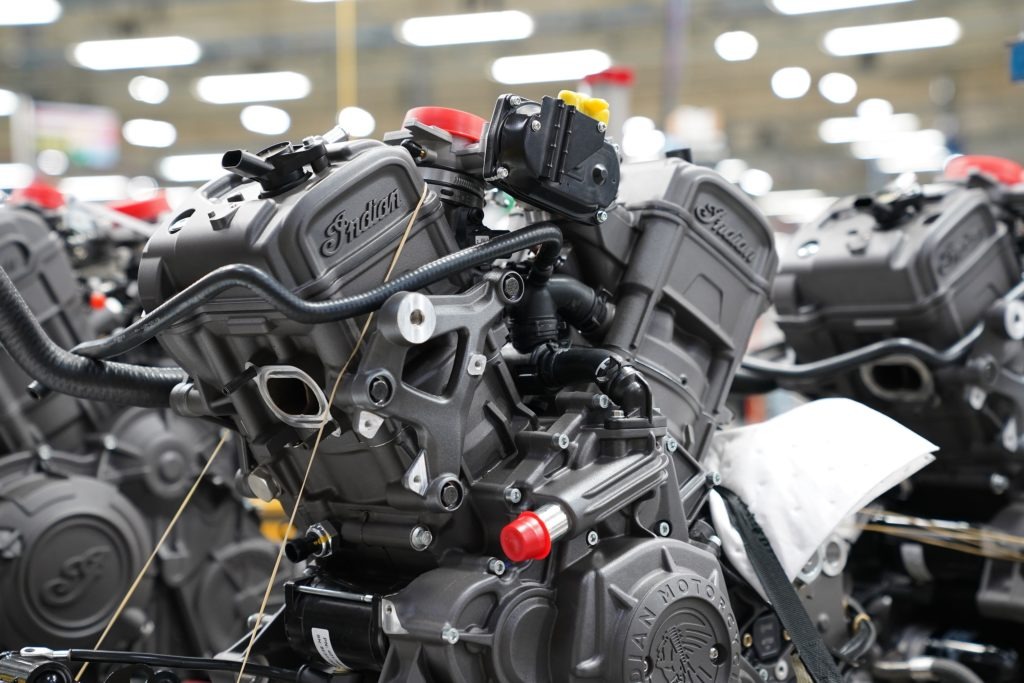

“Although the FTR shares a 60-degree Vee angle and 73.6mm stroke with the Scout,” Drevenstedt continued, “its engine is all new. With a larger 102mm bore (the Scout’s is 99mm), the FTR displaces 1,203cc (73ci) and it has a 12.5:1 compression ratio, high flow cylinder heads and dual throttle bodies. A low-inertia crankshaft helps the FTR rev up fast to its 8,000-rpm redline, and the Race Replica version’s Akrapovic exhaust is assertive without being too loud. Throttle-by-wire enables cruise control as well as riding modes that adjust horsepower, throttle response and traction control (full 123 horsepower in Sport and Standard; 97 horsepower in Rain). Being able to change displays or riding modes, turn off ABS/TC and adjust settings using the LCD touchscreen was so intuitive that I wonder why more motorcycles don’t offer such a familiar, smartphone-like interface.”

While 40 or so miles of riding was done on a sandy, rocky coastal road (where the dirt track-inspired FTR acquitted itself surprisingly well despite its 500-plus-pound wet weight), it was the on-road testing that allowed the bike’s abilities to shine. “Attacking curves at a fast pace,” Drevenstedt says, “the FTR was in its element. Plenty of torque throughout the rev range launches the FTR like a cannonball off the line and out of corners, and its chassis is robust and responsive. Stock suspension settings are on the stiff side, good for spirited cornering but a tad firm for cruising around town; adjust as you see fit. An assist-and-slipper clutch makes it easy to change gears even when riding aggressively, but the lever has a very narrow friction zone. A quickshifter would be a great addition to Indian’s extensive list of accessories, which offers a wide range of customization options.”

Drevenstedt’s sum-up? “The Indian FTR 1200 S is the make-no-excuses, American-made performance bike we’ve been waiting for. It’s not perfect—there’s too much vibration in the grips, which repeatedly left my throttle hand numb and tingling (cruise control to the rescue!), and the engine radiates a fair amount of heat, which roasted my thighs during the hottest part of the day and when riding at a slow pace. But a few rough edges hardly diminish what the FTR1200 represents—a cool-looking, hard-charging, corner-carving street ’tracker with state-of-the-art technology that’s made right here in the good ’ol U.S. of A.”

Pretty hard to argue with that – even if the path from prototype to production was a bit challenging at times.