It’s difficult to imagine a world without motorcycles. It’s equally tough to imagine ourselves in the picture during those days when they finally came along, but let’s try.

It’s 1901, the turn of a new century. You are well-read, and you get news and information from newspapers and magazines. Most of the country still has no telephones, but there is the telegraph for urgent news.

A network of railroads crisscrosses the nation, offering efficient transit for an American population that is reaching 80 million. Aware of the progress being made in the country, you marvel at the hydroelectric plant Westinghouse has built at Niagara Falls, ushering in the future use of Edison’s electric lighting and general electrification of the world.

Related: Venerable V-Twins: America’s Motor for More than a Century

You’ve heard of a man named Ransom Olds who is attempting to manufacture affordable horseless carriages in a small town in Michigan. The recent fire at his factory has left him with only one prototype, but he persists. You ponder whether the concept of powered personal transportation is even viable in a huge nation where no more than 4% of the roads are paved – and those are found only in major cities.

As you head to the barn to feed and water your horse, you wonder how your neighbor is getting along with his new “safety” bicycle (which followed the high-wheeled penny-farthing) and whether it is a fad or if the contraptions are here to stay. You wonder if there is any truth behind the rumor that George Hendee, the famous bicycle racer-turned-businessman, will be manufacturing his Silver King pedal bicycles with an engine.

What sort of gasoline engine is required to do that? You’ve read journals that suggest the engine by the French firm De Dion-Bouton might be suitable. This single-cylinder operates at 2,200 revolutions per minute! It would be even higher but for the limits of carburetion and ignition. You wonder if simply putting an engine in the frame of a bicycle is a solution to creating a proper motorbike in the first place.

Your study of the subject of motorcycles has led to the conclusion that two simple problems remain: the motor and the cycle.

In your experience, equines have minds of their own, are expensive to keep, get sick, and eventually die. Your friend’s bicycle is cheap and would take you where you want when you want so long as you had the legs and lungs for it.

Neither option appeals as much as the promise of new and modern thinking, embodied in a machine that doesn’t need to be pedaled, doesn’t get sick, and never gets tired. Lots of smart folks all over the world are working on this, so you are curious to see what happens in the near future.

Five years later, things have changed dramatically. Your neighbor sold his bicycle, among other things, to pay for a secondhand Duryea automobile. The car is not as trustworthy as hoped, and places to buy gasoline are hard to find, limiting their range. Winter weather demonstrates shortcomings in traction, weather protection, and starting capabilities. It does not climb hills well. A horse and buggy does better under such duress and when the car is broken down. But the Duryea is the only car in town and the first one many people have seen.

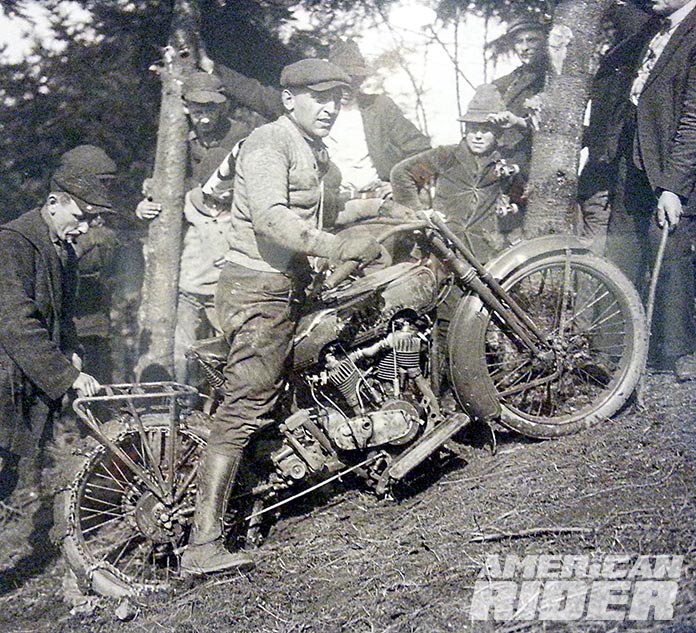

Newspapers announcing Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency come to town on an Indian motorcycle. You have an informative chat with the mailman discussing the merits of his new ride. He says Hendee’s machine is quite a good one and believes Hendee’s partner in the enterprise, Oscar Hedstrom, is a terrific designer.

Related: Harley-Davidson at Daytona and the Flathead Farewell

In essence, the Indian engine is a highly developed and improved version of the De Dion-Bouton, but an enabling feature is a spray-type carburetor invented and patented by Hedstrom. A twistgrip control enables the machine to be operated with both hands on the handlebar. The cushion fork helps the rider to keep control over bumps and dips and adds to rider comfort along with the English-design saddle. The range of 75-85 miles is adequate. The power of almost two horses from a vehicle weighing a mere 110 pounds is an appealing proposition.

Indian is clearly one of the better choices available amongst a bewildering variety of machines from a booming industry. Most newly minted manufacturers, in contrast, are shoddy assemblers who have simply jumped on a bandwagon. Your passion for motorcycles has taken root, but you need to save money and do more research. You want a motorcycle but need to balance passion with practicality. The neighbor’s haste with the Duryea is an experience you do not want to emulate.

By 1912, you are dazzled by the sweeping changes in America. President Taft cleared out the federal stables at the White House to make a garage. New Mexico and Arizona are admitted to the Union, making 48 states. An unsinkable British liner struck an iceberg and went down in hours with great loss of life.

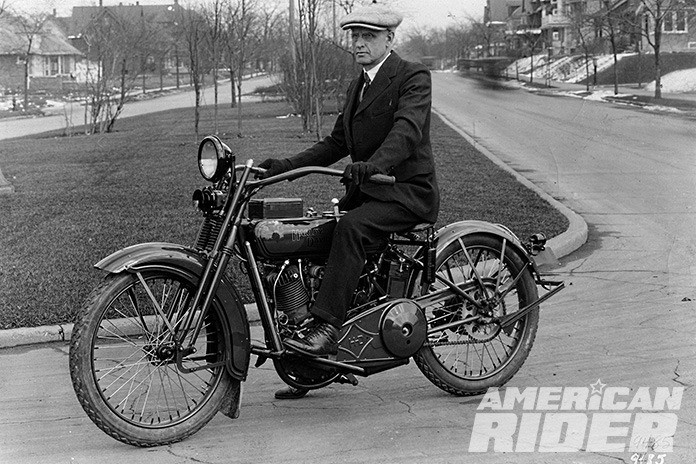

There are now telephones in the largest cities in your state, and the main street in your town is paved all the way to the courthouse. You are thrilled that there are six cars in town: the Duryea, a Packard, a White Steamer, and three Fords. The rural mail carrier is still riding his Indian Single with a sidecar, and you have finally managed to afford a used Indian Twin.

You decided on Indian largely because of a new cradle frame that is much stronger than the old diamond type and lowers the center of gravity as well as the rider position. And it has a chain drive, while most others use leather belts that slip too easily for your taste.

You ride a great deal, especially since your old horse is ailing. There is joy to be found in the feel of the wind at speed, of the sounds, smells, and euphoria that accompany the execution of bends in the road. You begin to think about buying another machine, narrowing down your choices to either another Indian or a Pope, Merkel, Emblem, Thor, Yale, Excelsior, or Harley-Davidson.

By 1917, you have gone from impecunious youth to prosperous middle age. There has been more progress since the turn of the century than your ancestors experienced in generations. Skyscrapers are America’s contribution to architecture, and there’s never been anything like them in history. Powered flight, once thought impossible, is constantly in the news. Moving pictures are an entertainment mainstay, with several cities building special movie houses to show them. Marconi’s radio is used experimentally in New York and California with expectations of commercial use very soon.

Cars, once a rarity, are commonplace, especially Ford’s ubiquitous Model Ts, which make up half of the cars on the road. Hudson introduced an auto with a roof and windows back in 1913, and other makers have since followed suit. From sea to shining sea, the United States has become a hotbed of innovation. Your beloved motorcycles have been a part of that.

You recently received brochures in the mail from the Big Three and studied them closely. You overlook the bicycles and lightweights available from all of them and hone in on a Big Twin.

In the end, a big country needs big motorcycles. The appeal of the mechanism plays a part as well.

All three Big Twins available – the Excelsior Super X, Indian Powerplus, and Harley J – have similarities: a 61ci V-Twin engine, a 3-speed transmission, a brake on the rear wheel, automatic oiling, chain drive, a foot clutch, a tank shifter, foot boards, and full electrics or magneto versions. Best of all, starting is no longer by means of bicycle pedals.

The Indian features suspension at both ends by leaf springs, while the others have rigid frames with spring-suspended seat posts. The Indian shifts on the right, and the throttle is on the left. The Big X and Powerplus have the kickstarter on the left, with Indian’s placed in the middle of the primary and Excelsior’s behind it. The Harley’s kickstarter is on the right as an extension to the gearbox.

The approach to the shape and mounting of the gas tanks differs for all three. The Excelsior has a bolt-in frame rail above the engine to facilitate top-end removal with the engine in place. Your decision of which motorcycle to buy dwells in these details of construction. All three are as good as or better than those made elsewhere. Riding any of them would be exciting.

But news of a sinister nature begins to cloud an otherwise bright future for the motorcycle.

In May of 1915, a German submarine sank the British liner Lusitania, killing 128 Americans and putting the U.S. on high alert. By the autumn of 1916, American motorcycle companies had been asked by the government to build bikes for the military. Woodrow Wilson was narrowly reelected the same year, in part because he had previously kept the U.S. out of the war.

But on April 2, 1917, having decided that the U.S. could not remain neutral, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany. This would be a conflict that closed the chapter of the first American motorcycles and opened the next one.