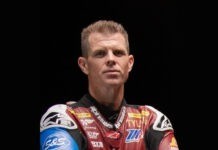

Gene Romero, 1947 – 2019

Words by Art Friedman

Photo courtesy of the AMA

Gene Romero, 1970 AMA Grand National Champion, AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame inductee and 1975 Daytona 200 winner, died in Fullerton, California on May 12, just ten days before his 72nd birthday. A lifelong smoker, he suffered from COPD and had been hospitalized with pneumonia. He is survived by his wife and adult son.

Romero may be best remembered by those who’ve seen Bruce Brown’s classic motorcycle film On Any Sunday, which primarily followed the season of reigning Grand National Champion Mert Lawwill. The series had wound down to the last two races, with several riders still in contention, among them Lawwill and Romero. Before the second-to-last race, the Sacramento Mile, Romero made his famous quip: “I don’t want to hurt anybody, but I just gotta get out there…get third, or come and visit me at the hospital, man. I dig carnations.”

He did better than third. He immediately put his C.R. Axtell-tuned Triumph at the front of the pack and stayed there all the way to the flag, securing the 1970 Grand National Championship. Then, to put an exclamation point on his title, he also won the last race of the season, the Ascot Half-Mile, the following week.

With his movie star good looks and charismatic, devil-may-care persona, Romero, or ‘Burritto’ as he was nicknamed (he spelled it with two Ts), seemed like the epitome of a motorcycle racer to many. But as a journalist I appreciated his ability to articulate matters, and especially his quick wit. If a race report seemed too dry, talking to Burritto would often add some fun to it.

Once back in 1977, at the roadraces in Loudon, New Hampshire, a reporter asked Romero a cringe-worthy question. After establishing that the factory Yamaha TZ750s that he and teammates Don Castro and Kenny Roberts were riding were all essentially the same, the reporter asked, “So then why does Roberts go so much faster than you and Castro?”

Everyone in motorcycling knew that Kenny Roberts was the best motorcycle road racer in the U.S., and probably in the world. But Romero decided to have some fun. So without a moment’s hesitation, Burritto replied, “Because we have better mechanics.”

“Better mechanics?” the puzzled journalist responded.

“Yes.”

“You have better mechanics than Roberts?” the reporter tried again.

“Uh-huh.”

“But Roberts goes faster?”

“Yes.”

“If you have better mechanics, shouldn’t you go faster.”

“No.”

“If you have better mechanics, why does he go faster?” the scribe queried, finally asking the right question.

“Because our throttles close. His don’t.”

Romero was initially regarded as a TT specialist, and his first National win was in 1966 at the TT at Castle Rock, Washington. Though he never won an AMA National Short Track, he soon showed his wider talents, winning National Miles and Half-Miles too, a total of 12 Nationals in all. But his most memorable victories may have been in National road races, which was helped along when Yamaha drafted him when Triumph’s fortunes began to wane. Although he was a bit big for the Yamaha TZ350s, the introduction of the TZ750 in 1974 provided him a tool perfectly honed for his talents. He closed out 1974 by winning the Ontario 200, the second-most-prestigious race of the year, against a star-studded field of international stars.

Winning major races like that positions you to be invited to big invitational events. Since they aren’t part of a series, you are paid well just to show up.

So when Gene Romero arrived at Daytona the following March, he expected the promoters of the Anglo-American Match races, a six-race event then held every Easter at three tracks in England, to stop by to negotiate. By mid-week Romero was more than a little peeved. Not only hadn’t the promoters looked him up, but they’d blown him off, even while signing up riders that might have been regarded as lesser lights. Apparently, they didn’t think Romero was a “real” roadracer. But they still had a couple of slots to fill, so perhaps…

But then Gene Romero hardened his negotiating position in the Daytona 200, still the biggest motorcycle race in the world at that time. For the first 100 miles he settled in among the top five, then as the race wound down and riders got tired and tires began to wear, Romero turned up the volume, passing “real” roadracers such as Steve Baker and multi-time world GP champion Giacomo Agostini, then pressuring Steve McLaughlin until McLaughlin crashed out.

In the victory circle, I watched as one of the Match Race promoters came up behind Burritto and quietly said something in in his ear. After the ceremonies, I caught up to Gene while he walked back to his pit. I told him I noticed the exchange. Did they want to sign him now? “Yeah,” he grinned, “They do, but I told them I have an appointment to get my car washed that day.”

After retiring from motorcycle racing in 1981, Romero briefly raced cars, then managed Honda’s flat track team from 1982 to 1985, and then formed a promotion company that produced events including motorcycle races.

We haven’t heard about funeral arrangements, but we’re planning to send carnations.4

Art Friedman was the Editor-in-Chief of Motorcyclist for 15 years, has been a moto-journalist for nearly five decades, and is responsible for hiring Thunder Press’s current Editor into the industry. But don’t hold that against him.