It’s not like there’s a problem with Harley gearboxes that your choice of gear lube is gonna magically fix. You can sure forestall plenty of issues and improve the action with a little thought and a slick choice of lubricant, but basically it’s a nonissue. On the other hand, you can’t seem to go anywhere (literally) to avoid the kind of lubricant problem that soils your machine and your pant leg. Thing is—the more I ponder it—the more it seems to me that the core issue isn’t lubricant as much as it’s air flow… internally. So, our transmission oil treatise will be completed another time. Instead, for now, let’s just cut to the chase regarding so-called “oil carryover” and how much conventional wisdom about these oil leaks really boils down to a lot of hot air.

Let’s be clear: there won’t be a whole lot of theory here, because we should focus on workable solutions for Sportsters, Evos and Twinkies alike since all are afflicted. Furthermore, don’t look for the cure, as I’m pretty sure it doesn’t really exist. The best we can hope for is to ameliorate the built-in conditions we have been presented with by engineers who are stuck trying to comply with Federal regulations. Mostly though, our mindset needs to change a little bit. You see, the real benefits to be had from dealing with oil carryover have a hell of a lot more to do with engine longevity, improved running, effortless response and, who knows, maybe even a bit more power than it has to do with oil spots on your pant leg or paintwork. When you put that in perspective you begin to appreciate the big picture instead of focusing on cleanup campaigns employing illogical added on doo-dads that mask symptoms rather than resolve issues.

Ground rules for this exercise include:

Engines that are otherwise in good health—rings are sealed, oil isn’t overfilled and various critical seals and O-rings are intact and working—all the basics squared away. Trust me; defects anywhere, most especially in the ring seal, can aggravate oil carryover massively.

The definition of oil carryover is oil where it isn’t supposed to be while the engine is running. Sumping, on the other hand, is oil getting into the crankcases when the engine is not running. With the advent of oil “reservoirs” under the engine wherever practicable, the Sportster and the Softail are the only Harleys left with oil tanks above the crankcase. So sumping isn’t as prevalent these days as oil carryover.

It’s almost a cliché that high-speed running makes oil carryover worse—sometimes much worse. Simply put, that’s because oil gets caught up in the airflow inside the engine and it can’t drain down via gravity like it’s supposed to. Speaking of clichés, one of the most hackneyed is that “engines are like a pump,” which is true and usually leads immediately to some follow-up platitudes about improving the efficiency of that pumping for the sake of more horsepower. What isn’t nearly as well advertised is that a Harley engine is really a double-action pump. The pumping that goes on above the pistons makes the power, but the pumping going on under them powers the root cause of oil carryover. Just as you wouldn’t want oil in the combustion chamber because it fouls sparkplugs and coats pistons with carbon, it isn’t good to have any more oil than necessary in the crankcase because at high engine speeds it gets caught in the hurricane winds fast-pumping pistons create inside the engine.

We talked about upgrades to oiling a few months back, in particular improving the efficiency of this second pump’s “action,” which is really the reason Harley (and the aftermarket) have been busy increasing the scavenging capability of oil pumps over the last few years. (It turns out that it’s not only the scavenging rate but also the ratio between the feeding and scavenging that our engines are sensitive to.) All well and good, but we know the aspect of oil carryover that we see has more to do with the amount of oil that gets transferred into and trapped inside the rocker boxes—oil carried there via the internal airflow. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Here’s where it gets a little complicated.

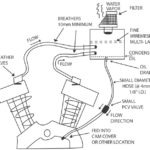

Since the days of the first overhead valve Big Twins, air pressure from the bottom end of a Harley engine was vented (or “breathed”) out of pipes and hoses from both the crankcases and cam gear cover. The gear cover vented back to the oil tank and the crankcase to the atmosphere. Simple, if a little sloppy, since after a hard ride the crankcase breather could (and often did) contribute its fair share to the legend of “marking its spot” that Harleys are saddled with to this day. (At least they didn’t mark your wardrobe, like they do now.) We have the EPA to thank for that, actually, since they forced H-D engineers to rethink engine breathing—again and again. Iron Sportsters and Big Twins from day one to the end of the Evo era used a so-called “timed” system conceived by Bill Harley, intended to help out the oiling system (ironically) by controlling the extreme huffing and puffing going on inside those old engines. That’s what H-D engineers had to work with when the Feds decided it was no longer acceptable to allow “fumes” to escape the confines of the cases. Two major developments occurred quickly, by Harley standards. First off, Sportsters lost the timed breather (in favor of an “asymmetrical” one that wasn’t) and then we got air from the bottom of the engine pumped up into rocker boxes. By the time those “features” were in place, work was well under way on the Twin Cam engine, the first-ever Harley motor designed to treat breathing and oiling as separate functions… sorta… therefore sporting neither timed breathing for the cases nor “mixed circulation” of oil and air as all of the earlier engines did.

The fact is, all of this “development” works better in theory than Bill Harley’s original setup—but none of it works perfectly, largely because of what has not changed in Harleys, notably the capricious nature of airflow within big V-twin engines with small crankcases, which vacillates between huge pressures and major vacuum thousands of times per minute. There’s not much we can do about that, but here’s what we can do.

Keeping oil in by letting air out has its up and downs. One clue is that hot air wants to keep rising and oil drops far better when it’s not blown around by, or mixed with, said hot air. Meaning—among other things—the separation of oil and air happens best outside the confines of the engine. Harley still gets by without an external separator, although (as study will quickly show) the newest factory breather/separator lash-ups are migrating ever upward and outward. Meanwhile, at least one other manufacturer of big-inch, air-cooled V-twins uses a sealed section of the frame tubing for this function. By plumbing lines into a spacious, sealed forward section of the backbone, the air/oil can separate leisurely, oil draining from the low area of the frame (still above the top of the engine) while air vents from the top into the air box. There’s merit in this and we can benefit from insightful interpretation of this kind of “out of the (rocker) box” thinking—if we wish. The whole idea here is that we want oil in the top of the engine to drain back down again and we want air pressure to either assist in that endeavor or get outta the way. From old to new—here’s some tips and tricks to show us what that might look like as we take a glance at some options for specific engines.

Twinkies from ’99-on benefit hugely from the so-called “hybrid” cam plate/oil pump kit upgrade (#25284-11) and from these, the latest factory iteration of rocker box breather, as used on new 103″ engines. The kit means less oil traveling as far as the rocker box in the first place and this breather valve design has more volume to handle air-oil separation functions for what little remains—a win/win, if ever there was one.

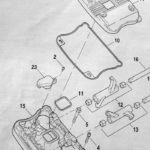

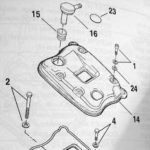

Early Evo Sportsters have much to gain from updating to the 2007-style oil pump and a swap to Buell XB rocker boxes. As shown here, you eliminate one pesky potential leak and lose ineffective umbrella valves, while gaining effective PCV valves that vent out of the rocker box altogether. All you need do is install these parts, plug the existing head vents (using P/N 868A) and “creatively” (Ahem!) re-route the hoses from the PCV valves… possibly to a “catch can”… if you catch my drift.

“Head breather” Evo Big Twins (1993–2000) are great candidates for upgrades like an S&S HVHP oil pump, reed breather valve and rocker box upgrades very similar to those of the Sporty/XB—although they would need the lower box as well, to complete the ensemble. Clearance (or style) issues might sway Evo fans into an alternative that keeps the breather/separator inside the box, like the one we see here, where the upgrade takes the form of complete 2004-and-later stock Sportster rocker box assemblies. Either way, these improvements, in concert with one another, are notable.

By the way, it’s really the right crankcase half that makes a head breather, with its lack of any compartment to allow oil to settle, nor any sort of bottom venting for either the crank or the cam. This is the biggest reason S&S only recommends their highly effective reed breather valve for this configuration.

Early Evo Big Twins (1984–’92) simply did not have air intentionally routed to the rocker boxes, instead allowing air/oil to vent directly from the crankcases and/or cam case. Hence the term “case” breather. Employing a rotating breather valve, “timed” to use pressure waves in the engine to assist with engine oiling duties. It was a system that worked fairly well for low-output engines operating in a fairly narrow rpm range. Today big-inch, high output, free-revving performance depends on proper tweaks to that system. The swap from a timed breather to S&S reed breather is fundamental to improved case breathing, but it works so well at evacuating the crankcase, it might problematically overfill (and overwhelm) the “settlement compartment” in the gear case cover. Adding the S&S HVHP oil pump (as shown) should keep the oil levels down to a manageable level.

And one can always resort to tricks similar to this one to keep the oil outta the air! As simple and effective as it gets (for a motor that’s otherwise in good order) this “snorkel” made of a shaved-down 90-degree copper elbow, should prove invaluable in exorcising the demons from case breather settling pockets, with (or without) reed breathers and High Volume High Pressure oil pumps.

It also never hurts to cover the basics. With the case breather case that amounts to a clean routing of breather hose to a level approximately that of the rocker boxes and then into a catch can or back along the rear fender to a point behind the tire. This photo shows a little extra insurance in the form of a hollow canister several times the inside diameter of the hose, used as a “burp” valve. The notion being, any excess pressure has a chance to dissipate at that point, allowing air to move on and oil to drop back.

Clever ideas for head breathers abound as well. Some as simplistic as building a homemade air-oil separator contraption—along these lines. The point is, internal (or better yet) external, no matter how primitive or sophisticated the hardware for these kinds of mods, the intent remains—breathing room for all the oil-free hot air you can manage.