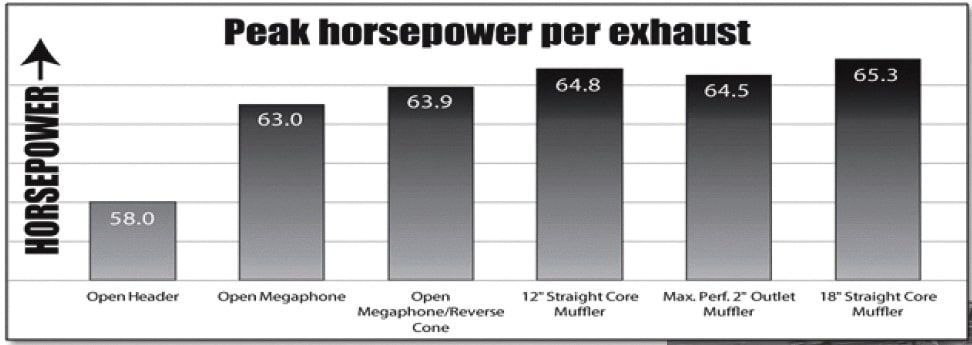

Ya gotta envy the car guys. Corvettes, Mustangs, Challengers, Camaros and others have plenty of room to hide huge, elaborate exhaust systems and the electronics to control them. The result is genuine performance and legal, soul-satisfying sounds motorcycles can’t hope to match. Part of the problem for V-Twins stems from the “shorty” syndrome – the notion, etched into H-D fans’ brains for decades, that small, straight-through mufflers are good for performance. Damn the noise, full speed ahead!

Only, it doesn’t really work that way these days.

Honestly, most of us just want our V-twins to sound good. An incidental increase in power is only a fringe benefit. With 80 decibels for a noise emission standard and disproportionately small mufflers to meet that standard, it’s understandable. We tend to think of noise and power as synonymous. They aren’t.

Noise created by an engine does not come from the explosion in the cylinder. Sound, being the result of air waves, cannot travel from an enclosed space. What you hear is the opening of the exhaust valve, at pressures considerably above that of the atmosphere. This sets up air pressure waves of indeterminate form and frequency, but well within the audible range of human hearing. One of the first difficulties encountered in a scientific approach to silencing without power losses is dealing with the pressure at this stage. Depending on engine specs, these waves exit at widely varying pressures, from as low as four or five psi to well over 100, and the intensity of the sound produced varies in more or less direct proportion.

If the gases escape directly into the air, they cause massive noise. Even a small gutted muffler fitted to a head pipe offers little interference in velocity, and still produces considerable impact with the air (noise) at the muffler outlet. To meet noise standards, the usual practice is to adopt some means of preventing this kind of direct outflow altogether by causing the gases to change the direction of flow and reducing their velocity so the sound produced is appropriately reduced. Basically, this means large-capacity mufflers, the volume of which should be no less than five times the capacity of the cylinder. (Read that again and think of ‘shorty’ mufflers.)

Baffles Are Baffling

Another method is to introduce cylindrical baffles with a multiplicity of holes, which break up the flow of the gases and in some cases promote expansion in stages. Typical examples have a continuous pipe through the center of the muffler, but the middle portion is plugged, and the adjacent regions perforated, so gases must first pass at right angles through the holes in the pipe, into the muffler shell and back into the outlet. Absorbent packing materials are often fitted to silencers, increasing their sound-absorbing efficiency by diffusing the gases and retarding their velocity. Plenty of variations exist, but there is no form of baffling that can entirely avoid setting up a certain amount of back pressure, and it’s damn difficult to convince racers that power output does not necessarily suffer when baffles are used.

Noisy Silencers?

Fitting a silencer/muffler, far from reducing noise, may actually increase it or make it more prominently audible. This is due to the effect of resonance in the exhaust system (nearly always present to a certain extent) in tubular and cylindrical passages, which have properties comparable to organ pipes in amplifying and modifying sound. The effects of this resonance are complex, and include not only the vibrations set up in the gas column but also those due to the natural frequency of the metal, superimposed on the cyclic frequency of the exhaust beats within audible range.

In The End

The shape of the exit of a muffler also has a definite effect on excessive exhaust noise, and this is most evident in the case of megaphones, reverse cones megs, fishtails, slash-cuts, shortys and so on. None of which, incidentally, have much internal space. It need not be this way.

Big Pipe, Big Noise

The common belief that muffler/pipe outlet area should be not less than the area of the exhaust port is a fallacy. The opening period of the exhaust valve is only about 1/4 to 1/2 of the engine cycle. During this period the progressive opening and closing reduces effective area to no more than half that of the full port. Moreover, the temperature of the gases, and therefore their pressure/volume, is falling rapidly in their passage through the exhaust system. Smaller outlet diameters affect noise, not power.

Total Exhaust-ion 101

Head pipes: Individual head pipes need to be correct diameter, equal length and proper length. (Stockers usually aren’t.) So-called balance or cross-over pipes can do a lot to correct deficiencies in basic head pipe configurations. Siamese (2-into-1) headers need proper lengths and diameters of tubing as well as a collector with correct diameter and convergent angles. Tuned headpipes are responsible for power generation.

Mufflers: Should be large-diameter, long, high cubic-volume ‘cans.’ Shortys, megs, reverse cones, fish-tails and such, are not. Mufflers are responsible for power ‘spread’ and reasonable, humanly audible noise levels. For example, stainless steel is acoustically dull compared to steel. Sheer noise may be equal but tone is not. (Decibel meters do not register sound qualities, only sound levels.)

Baffles: Should redirect and slow pressure waves as well as attenuate sound waves to achieve the best sound and overall power. The best designs are adjustable to suit conditions. So-called ‘back pressure’ is bad – period! Pulse tuning, on the other hand, is good but difficult. Anything you can see through will be loud. Something you can’t see through is still able to make more power with less noise.

So put that in your pipe and smoke it!

If you have any tech tips or questions or unsolvable motorycle mysteries, email motorhead@thunderpress.net