I bought my first new motorcycle in 1965. I handed the dealer a bit more than $600 and signed a few papers, and he gave me the key to a Ducati 250 Scrambler. Since that seminal event, I’ve purchased dozens of new motorcycles, with each transaction becoming a bit more involved – not to mention a lot more expensive.

We graybeards continually embarrass ourselves by referencing “the good old days.” This usually results from bad memories and too much beer. However, I can offer a good argument for the ’60s and ’70s being the ‘goodest’ of old motorcycle days. Back then, there were more than 60 different motorcycle brands available in this country, with dealerships seemingly on every other block. They weren’t all the most reliable motorcycles, but most were easy to work on, and parts were relatively cheap.

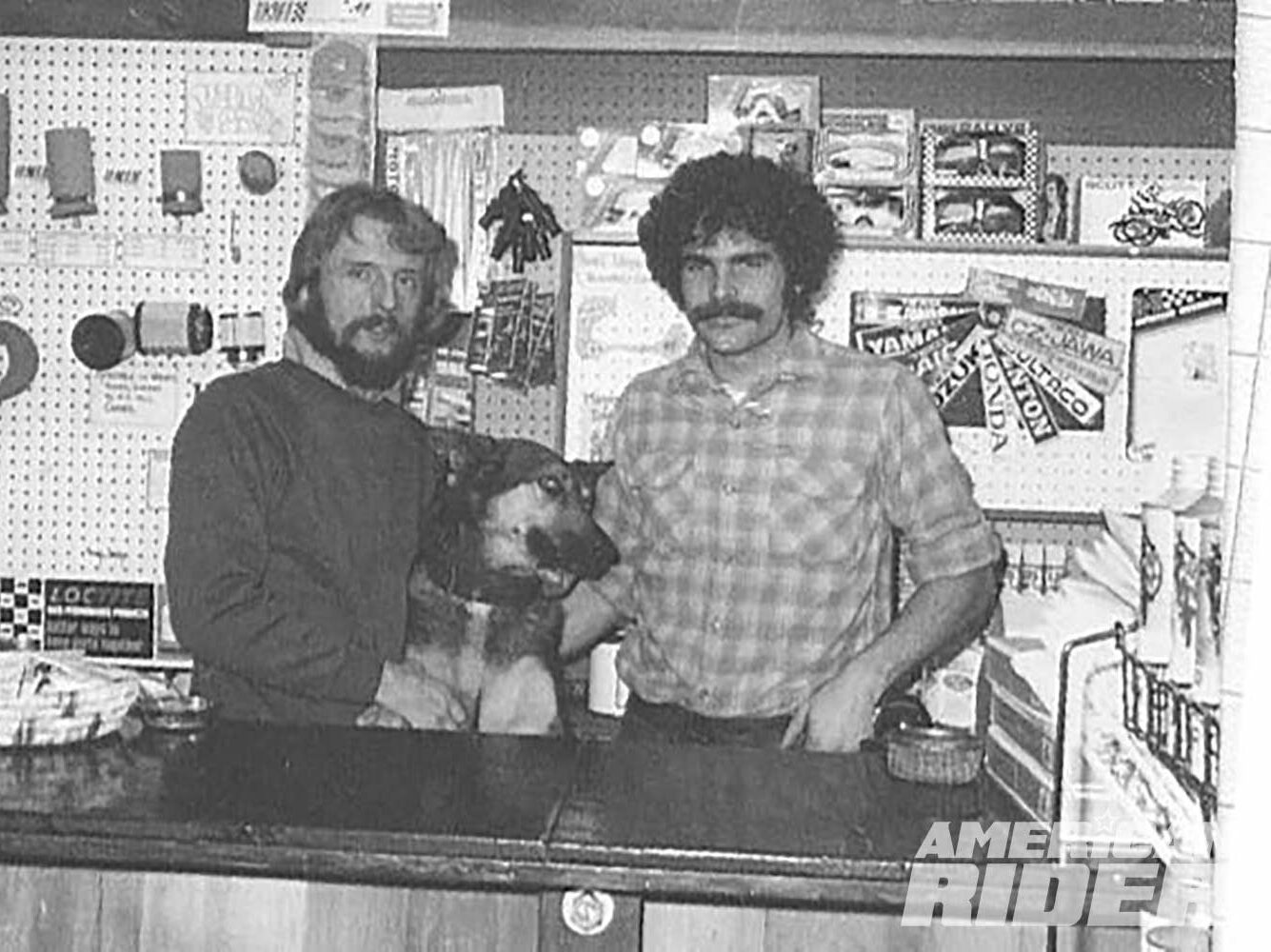

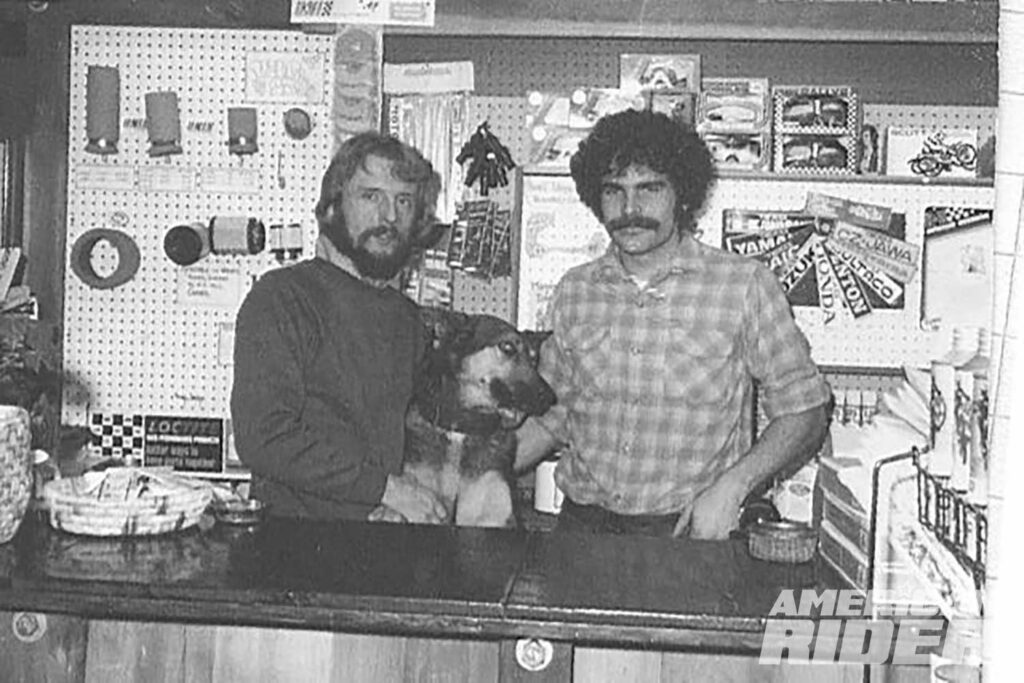

What also made that time great was the dealers themselves. Most were independent shops, owned and staffed by true enthusiasts. There was a passion around those places that is largely missing at today’s dealerships. Buying a bike, part, or accessory usually involved war stories, tips on where to ride, and lots of bench racing. The dealerships were meet-up, hang-out, and amp-up places that made you feel like you were a member of a select group.

Find more Unrepentant Curmudgeon columns here

The motorcycle boom of the 1990s saw many small shops morph into cavernous emporiums, which dramatically changed the dealership experience from passionate motorcycle camaraderie to the passionless hard-sell tactics familiar at car dealerships.

The Harley Owners Group was – and still is – the saving grace for Harley. While the dealerships themselves followed a path to sterility, HOG has kept the camaraderie flame burning. But things continue to change – and not necessarily for the better. When the motorcycle market fell on its butt post-2008, the money that had kept the doors open dried up. This resulted in closures, sales, and the consolidation of numerous dealerships (all brands, not just Harley).

This pattern continues today, particularly along the consolidation front. Operating costs have skyrocketed to the point where it is tough for an independent dealer to make money. This is where the economies of scale kick in. A corporation that owns several dealerships – eight to 10 is not unusual – holds tremendous buying leverage. The stand-alone brick-and-mortar store is a business model that is becoming very difficult to sustain, regardless of the product. Consolidation is a stop-gap solution. It’s workable for now, but it too will be pressured as operating costs continue to rise – and they certainly will.

So what does the future of buying a motorcycle look like?

In many ways, motorcycle retail follows the path of car dealerships. Increasingly, the larger Harley dealerships resemble businesses found on auto row. Inside, the camaraderie is replaced by adversarial jousting between sales and customers. Forget the camaraderie; it’s all business.

I’m closely watching the CarMax/Carvana process for buying used cars. Both Harley and Polaris, Indian’s parent company, have variations of this: H-D1 Marketplace and Polaris Xchange, respectively. My biggest concern with this concept is that it seriously handcuffs your ability to negotiate, and if successful, it could lead to the elimination of dealers, replaced by regional service centers. As is too often the case, these changes offer more benefit to the company than the customer.

In the 1970s, I owned a small dirtbike dealership with a parts-and-accessories business. Selling a couple of motorcycles a month and operating a healthy accessory counter allowed me to hire a small staff and make a living. That would be impossible today.

Comments? Try me at fogpirate@gmail.com