Hall of Famer Don Emde dishes the backstory on his fascinating and comprehensive new book The Speed Kings, which chronicles the formative, crazy, short-lived and often deadly world of motordrome boardtrack racing in the early 1900’s

Words by Mitch Boehm

Photos courtesy of Don Emde

There are lots of motorcycle books out there in the moto universe, but unfortunately not many really good ones. Fortunately for all of us, Motorcycle Hall Of Famer Don Emde’s latest tome on the roots, growth and ultimate demise of board track (or motordrome) racing – titled The Speed Kings – is very clearly in the latter category.

Having helped the legendary Malcolm Smith conceive, write and edit his 400-page, coffee table-flexing autobiography titled Malcolm! The Autobiography back in 2015, I know a thing or two about motorcycle books. Malcolm and I spent more than two years on the project along with his wife Joyce and art director Todd Westover, and I can tell you firsthand that producing a book like that – or one like Emde’s latest – is a mammoth undertaking, and very often years in the making.

The first thing that hits you when you leaf through The Speed Kings (aside from its impressive physical size, roughly 12 x 10 inches and a bit over an inch thick) is the jaw-dropping depth and quality of the research, writing, photography and illustrations contained within its 372 pages. You simply can’t believe the amount of historical stuff Emde has crammed into the thing, and you’re bound – as I was – to learn something new on damn near every one of those pages. This is motorcycle archaeology at its finest, and the question that seems to pop up every couple of minutes as one leafs through the tome is this: How the hell did he compile all this information?

We’ll get to the answer to that question in just a bit, but here’s a short overview that’ll give you an idea of just how much ground Emde covers in The Speed Kings.

It all begins with a fascinating overview of bicycling in the mid and late 1800s, which is of course where the whole motorcycle thing we know and love today actually came from. First were the large-front-wheel bikes – called ‘High Wheelers,’ or ‘Ordinary’ bicycles – you’ve seen in all those black-and-white images, some with wheels five feet tall. Later, at the end of the 1800s, came the more traditionally designed bikes – called ‘Safety’ bikes – with similarly sized wheels and, after John Boyd Dunlop’s wonderful invention of 1890, pneumatic tires replacing solid rubber ones.

Almost overnight, these suddenly modern and easy-to-ride bikes with air-filled (and thusly grippy and soft-riding) tires took the world by storm, with bicycling exploding in popularity all over the globe. Bicycle racing became increasingly popular, as well, and the big names of the period are all here: George Hendee, Oscar Hedstrom, Charles Henshaw, Arthur Zimmerman, Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor and many others.

In bike racing, ‘pacing’ – which was two-, three-, four-, five- and even six-person bicycles creating a draft in front of a particular racer – became all-important, especially for speed records. (‘Major’ Taylor’s world records were perhaps most impressive, as he was an African American athlete who faced serious discrimination). Of course, these ‘pacers’ needed to be as fast or faster than the racing bicyclist in question in order to create the all-important draft, and finding enough fit riders for the multi-rider pacing bikes wasn’t easy.

But with steam, electric and internal-combustion technology beginning to percolate in the late 1800s, these faster motorized single-rider ‘pacers’ soon took over, and one of the best of these was Oscar Hedstrom and Charles Henshaw’s De Dion-Bouton-based (at first) motorized bicycle and, later, their Typhoon model. All this winning by Henshaw- and Hedstrom-paced riders caught the attention of a certain George Hendee, who was then building Indian bicycles, and by 1901 they’d joined forces and built the first Indian ‘motocycle’ – with guys like Charles Metz, Alonzo and William Marsh, Edwin Thomas and of course William S. Harley and the Davidson brothers (among others) busy with their own motorcycle projects, as well.

Motorcycling expanded in the first decade of the 1900s, with more and more regular folks eschewing pedal-powered two wheelers for the ease and speed of motorized transport – and more and more folks attending races on horse-racing dirt tracks, one of the first of which happened on May 7, 1901 at Los Angeles’ Agriculture Park, later named Exposition Park and the current site of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

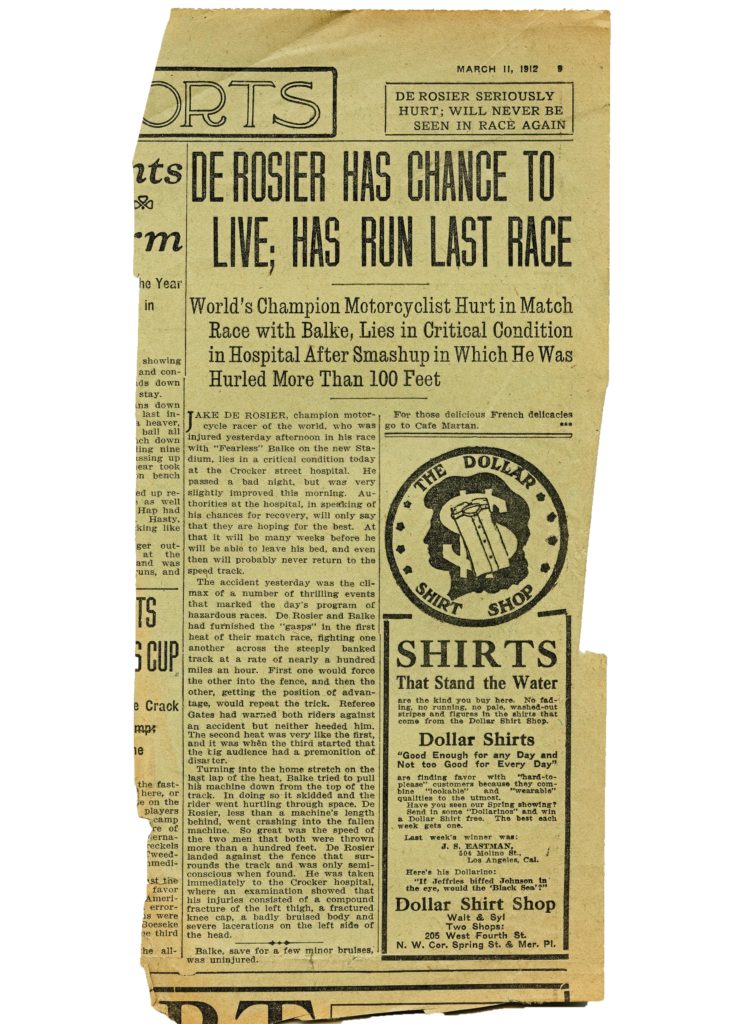

During that decade an official motorcycle association was formed (the FAM, or Federation of American Motorcycling, which organized events and sanctioned racing); rallies began to happen on the firm beach sand at Daytona and Ormond Beach; Indian prototyped a 42-degree V-twin in 1905, and then hired soon-to-be-world-famous racer Jake DeRosier to ride it. (He would not disappoint.) Dirt track races were being held at many venues, including So Cal’s Ascot Park, which would host them into the early 1990s.

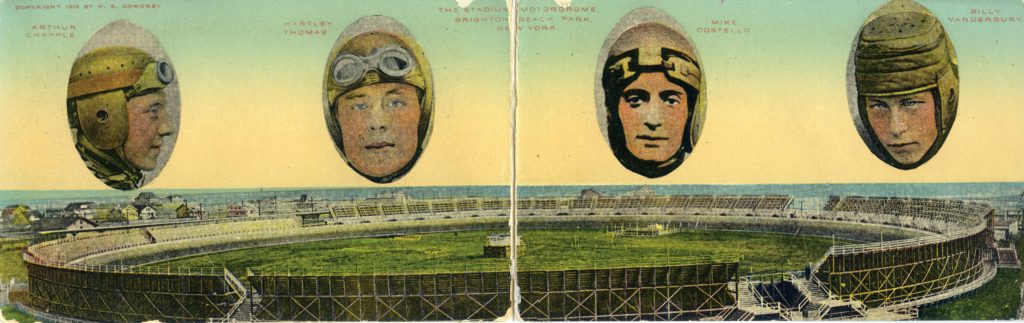

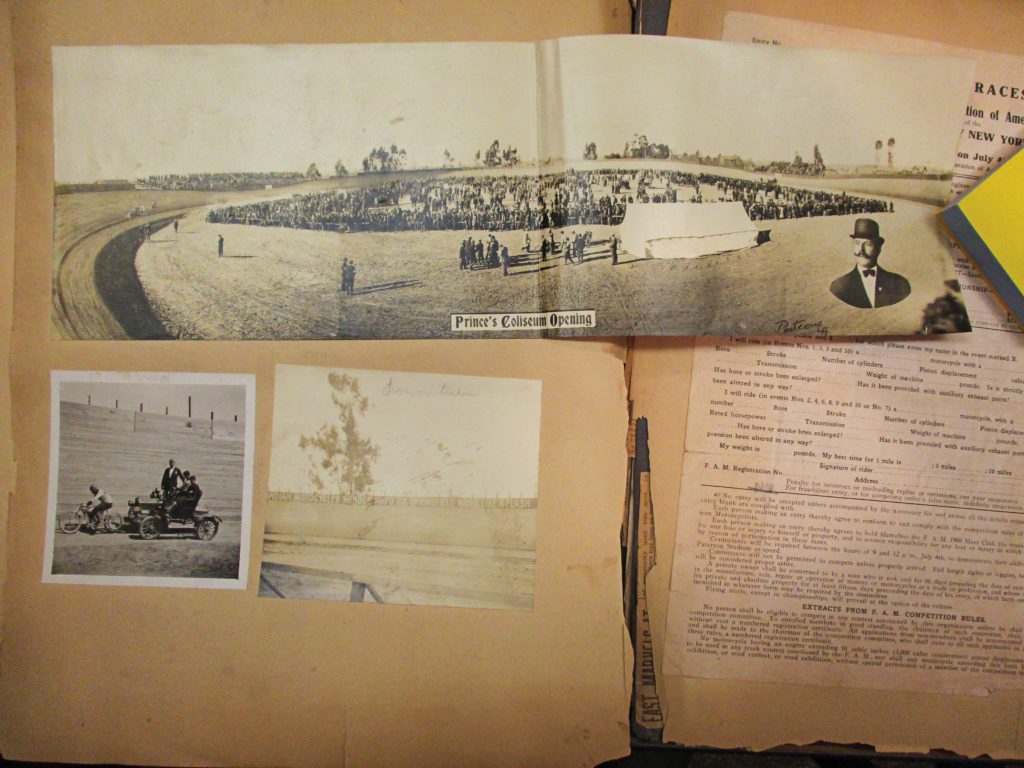

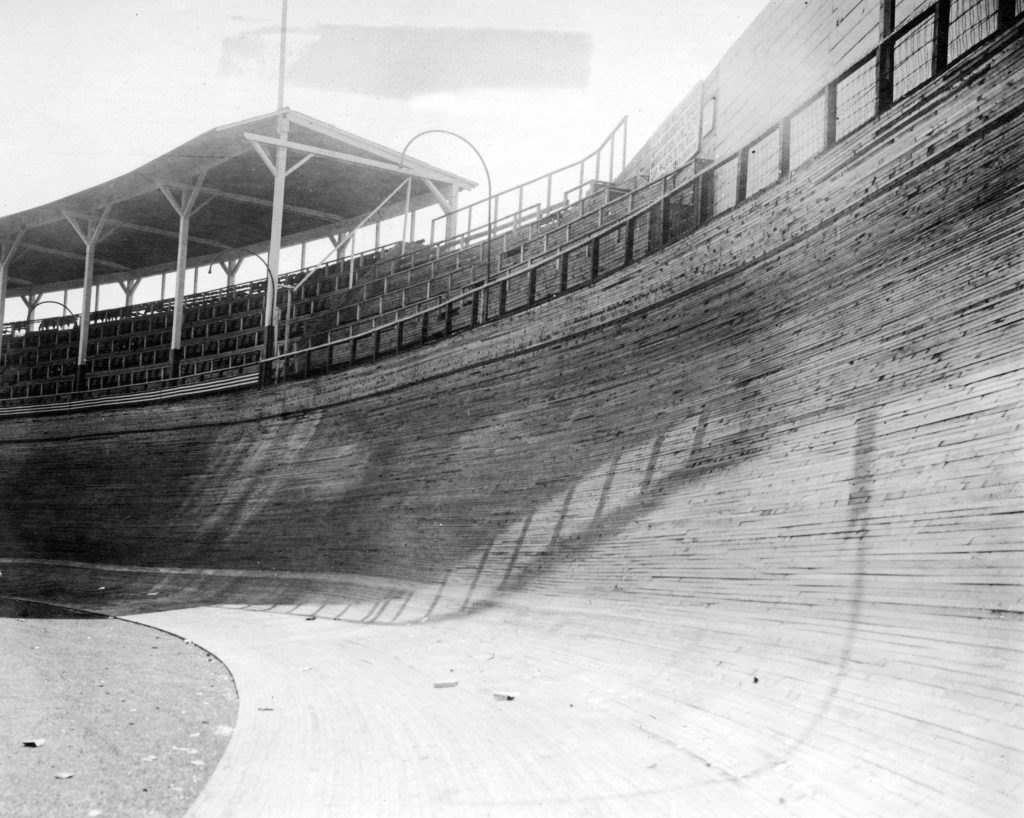

But perhaps the most important event in the sport of motordrome racing’s – and, indeed, motorcycling’s – history happened on Sunday, February 28, 1909, when motorcycles were first ridden on a motorcycle-only board track venue in Los Angeles, which noted promoter Jack Prince had built in just 30 days several blocks southeast of the Exposition Park. Prince’s wide-turn oval track, which he named the Los Angeles ‘Coliseum,’ was designed to be the fastest track in the world, and the average speeds of 80 mph during initial testing proved him to be exactly right. The heavily promoted first race meeting that happened on March 14 brought upwards of 10,000 paying spectators, and the racing between DeRosier and rivals Paul Durkum and Eddie Lingenfelder (and others) wasn’t just spectacular but record-setting.

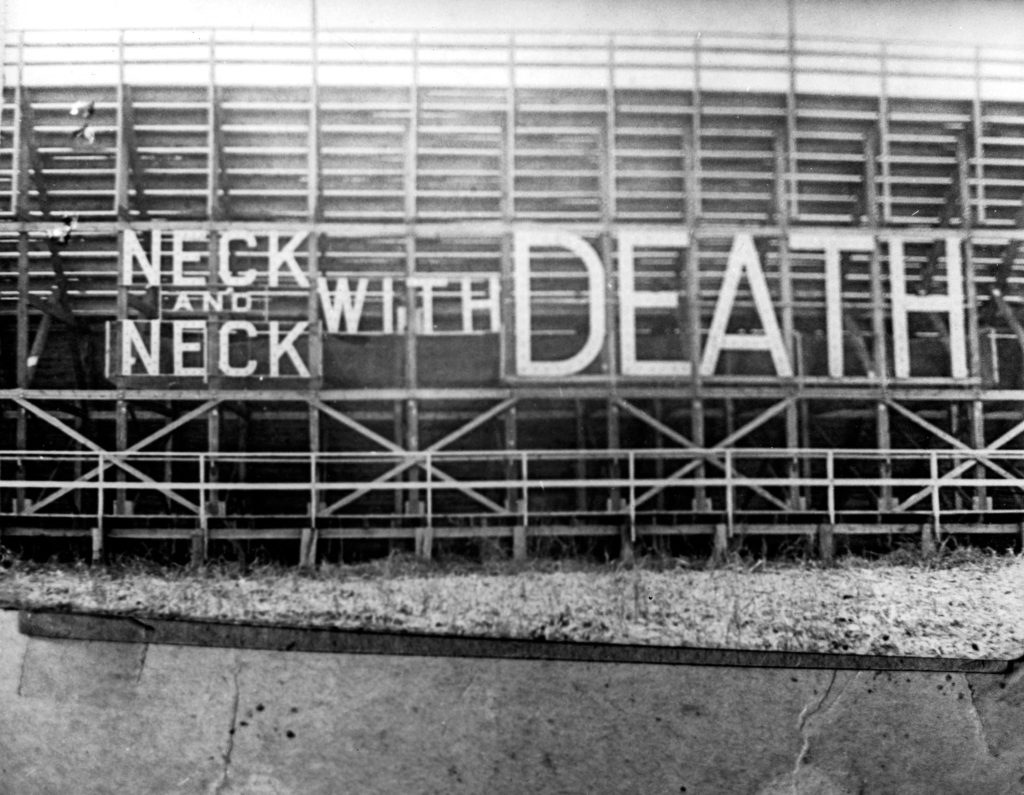

‘Motocycle’ racing, and especially this high speed and highly exciting motorcycle Motordrome racing in front of thousands of fans, had arrived, and would soon dominate the public’s attention and appetite …. for speed, excitement, heroes and, unfortunately, carnage. The sport grew quickly, with board track motordrome construction happening all over the country. By 1911 there were more than 100 motorcycle manufacturers, with many of them supporting racing teams, including Thor, Excelsior, Merkel and many others. Nearly 30 tracks would run races between 1908 and 1915.

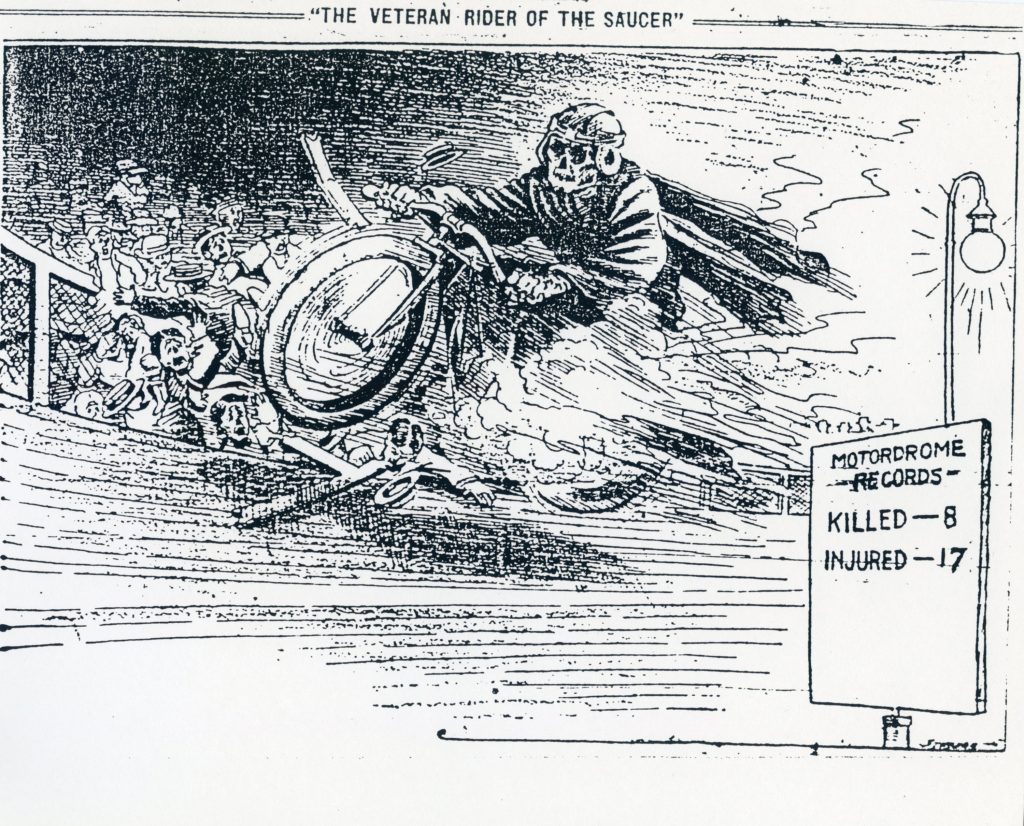

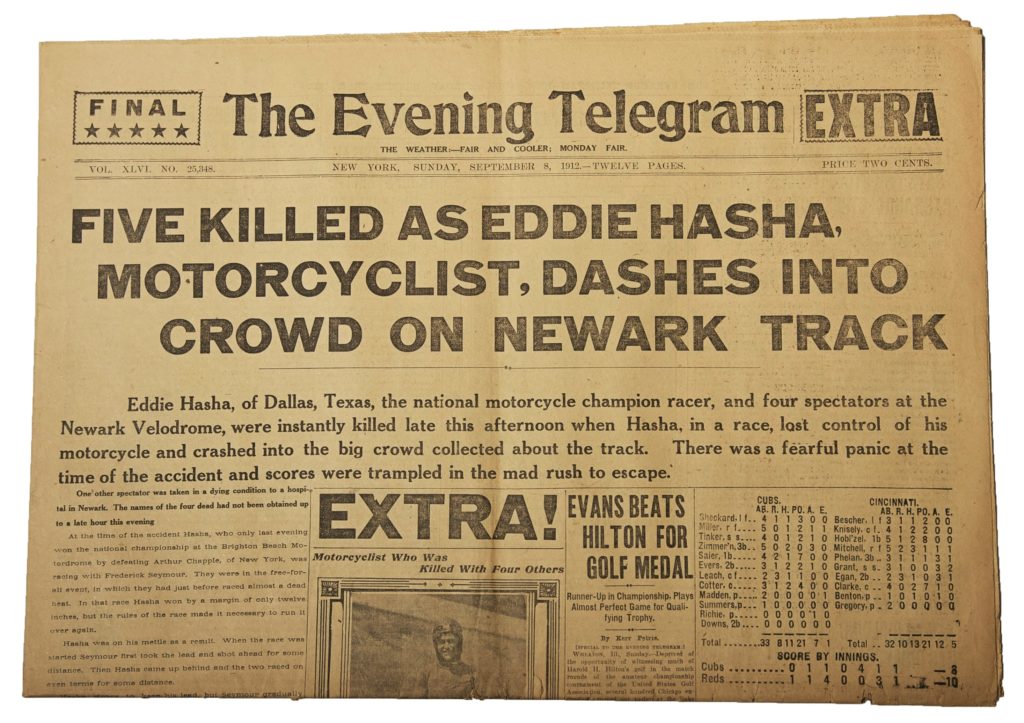

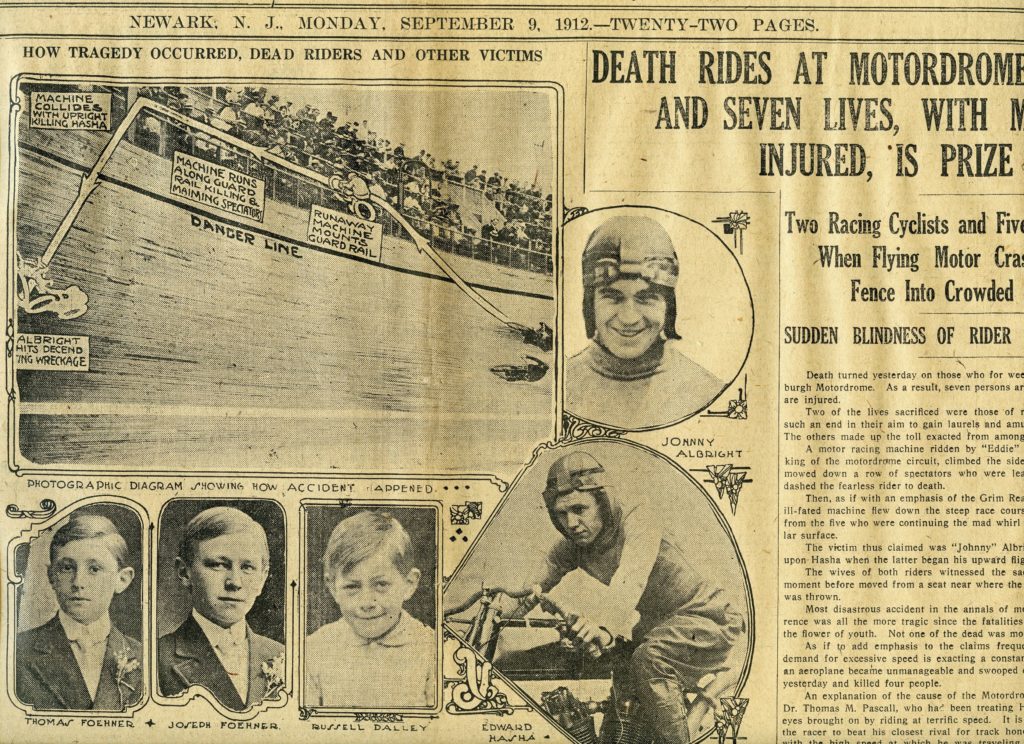

But of course the racing itself and the racing circuits these brave men competed on were insanely dangerous, and not only due to the inherent dangers of motorcycle racing itself, the common tire failures of the times or the road-rash and wooden splinters fallen riders would often endure. With steeply banked corners (near-vertical in some cases) and nothing more than wooden fencing and railings with deadly vertical posts separating the machines and riders from the spectators, ugly crashes and those involving spectators were bound to happen – and did, most famously on September 8, 1912, at the Vailsburg Motordrome in Newark, New Jersey.

During a six-rider ‘Free For All” race, rider Eddie Hasha lost traction while passing fellow rider Johnnie Albright and skidded at 90 mph into the wooden fencing, over which handfuls of spectators were leaning to catch all the action. Hashe’s bike cut through them like a scythe, killing six and maiming dozens of others for life. Hasha hit a light pole a half-second later and was killed instantly, as was Albright, who hit Hasha’s broken motorcycle and died of massive head injuries.

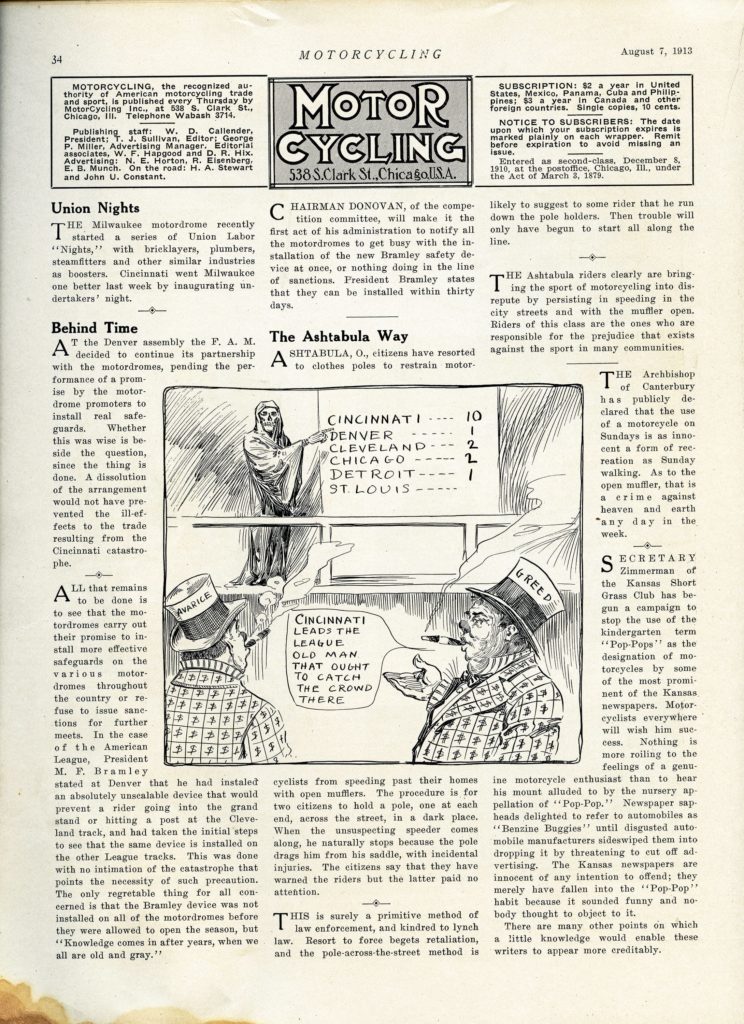

News of the accident resonated immediately and dramatically around the country and the world, with the press increasingly calling the motordrome venues ‘murderdromes.’ The name stuck, and soon the entire sport of motordrome racing – including promoters, track owners, teams and even the riders themselves – was looked at by the media and mainstreamers through a decidedly darker lens.

Things went from bad to worse when another tragic crash involving spectators happened a year later on July 30, 1913, at the Lagoon Motordrome in Ludlow, Kentucky (just across the river from Cincinnati) when racer Odin Johnson lost control after a front tire blowout and crashed into the upper track barrier and hit a light pole. His motorcycle’s fuel tank was blown apart, and the electric light Johnson hit ignited the fuel, which burned nearly 30 spectators and killed ten. It was a horrific and tragic scene, one involving involuntary manslaughter charges for the track owner and promoter, though courts eventually threw out the charges, saying there was not enough negligent proof to convict. The press went crazy over the incident yet again – and understandably so.

‘Safety’ measures such as better wire-mesh fencing were tested in the coming months, but the reputational damage to the sport was done, and the calls for the end of motordrome racing grew louder – especially after three more spectator-involved incidents happened in early 1914.

As Emde writes toward the end of the book, “It’s impossible now to know what had the greatest negative impact, but motordrome racing had lost its way. A sport that had been attracting thousands of race fans three nights a week was on its way out of business. Atlanta, Chattanooga, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh and the St. Louis motordromes were all closed by the end of 1914; some didn’t even make it that far.” Some longer, ‘auto-speedway’ boardtrack venues continued on for a few years, even after WWI, but the glory years of the format were gone for good.

Very interesting… but are these books for sale or what??

So, where can I buy this book?

that is Bobby Walthour jr. not sr.