Here be dragons

The continuing Age of Exploration

Columbus knew that the earth was round, as did other cartographers and educated people of the time. Even the average Hellenistic Greek and Roman citizen knew that the Earth was a globe that revolved around the sun. What Columbus didn’t know, due to a technical error made when Claudius Ptolemy calculated the circumference of the earth 16 centuries earlier, was the exact mileage to Japan. Columbus discovered that the world was much larger than it was believed to be, and those unanticipated 7,002 longitudinal miles would keep mapmakers gainfully employed for the next five centuries.

I’ve always been a cartomaniac. As a child, the walls of my room were covered in maps, primarily those retrieved from copies of National Geographic. If my family went on a weekend trip, I’d collect road maps at gas stations (they were free in those days). My fascination with cartography has never waned.

Cartography is the combination of two Greek words, chartis (map) and graphein (write). Topological maps are those that are drawn without regard to scale and contain only pertinent information. This is typical of what you or I would draw to provide directions to a destination. Representational maps show quantitative relationships like distance and spatial relationships and are exemplified by highway roadmaps and the more highly regarded topographic style.

Early maps were as much fancy as fact. The exploration of the “New World” in the 16th century fueled the public desire for maps. Cartographers combined detailed observations and hearsay information brought back by explorers with earlier maps made by other lithographers. Artistic license allowed vast uncharted regions to be filled with engravings of fantasy creatures or simply labeled, “Here Be Dragons.”

The first American road was established in 1673 as a postal route that simply followed the centuries-old native Pequot Path. The first city-to-city stagecoach line was established from New York to Albany in 1785 and construction of the Cumberland Road began in 1815. Very few maps show the extensive network of stage and transport routes that existed in the eastern United States during the early 19th century. Such maps simply weren’t needed as major roads were clearly marked and travel limited to less than 40 miles in a day under ideal conditions. It was the railways—not highways—that promoted the popularity of business and pleasure travel and generated public interest in “road maps,” and so it would remain for the rest of the 19th century.

When George Wyman made the first motorized transcontinental journey across the United States in 1903 on a California motorcycle, he did so more by dead reckoning than anything else. Years later, in 1919, the same situation faced Lt. Col. Dwight Eisenhower when the U.S. Army organized the first transcontinental motorized convoy (including nine Harley-Davidson and Indian motorcycles) to cross the United States. As strange as it might seem, there were no highway maps for the vast distance from the Mississippi River to the Sacramento Valley in California simply because for most of this distance there were no roads! The Army had to hire Henry Ostermann, a promoter for the Lincoln Highway Association, as a guide because he was the only person who knew the “route” from St. Louis to San Francisco.

Early automotive touring maps with point-to-point written navigational instructions—some even included photos for clarification—were published by competing bicycle, motorcycle, and automotive organizations. Each organization would mark their routes on telegraph poles and trees. Sometimes over a dozen different route markers would be posted at a single turn. In 1915 there was only one named highway, the Lincoln Highway, but by 1925 there were over 250 named highways and each had its own unique logo signage. The federal government was finally forced to establish a uniform numbering system and standardized shield marker for nationally funded roads in 1925. This ushered in the golden age of American roadmaps (1930–1960).

High-tech touring

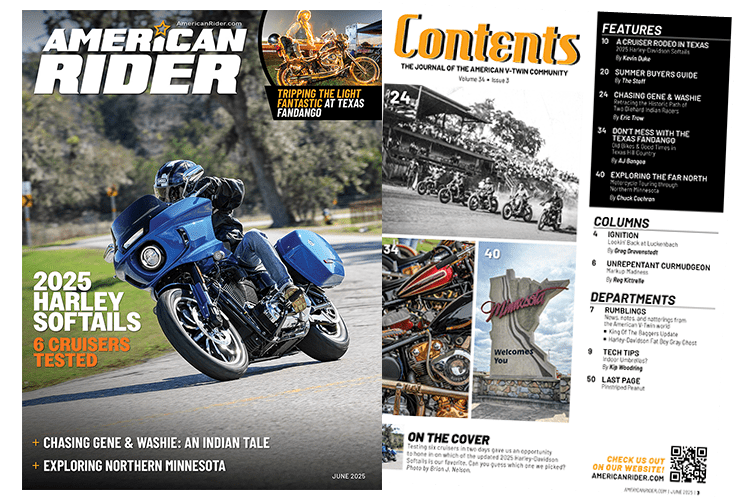

A mere decade ago the ultimate high-tech accessory for motorcycle touring was a map pocket with a clear acetate window on the tank bag. Today it’s a handlebar- or fairing-mounted bracket holding a Global Positioning System (GPS) unit—essentially an electronic globe, compass, altimeter, chronometer, speedometer and trip recorder all rolled into a single hand-held instrument. Providing accuracy with push-button ease, these units allow riders to efficiently navigate streets and highways while being distracted by tiny LCD screens.

GPS receivers used in survey work can register two points within a fraction of an inch, but most of us have to make do with commercial hand-held units where accuracy is measured in meters. Today’s regular receivers have an accuracy of less than 10 meters 95 percent of the time. Differential receivers (DGPS) increase this to 3–5 meters of accuracy (95 percent) and Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) receivers can place one within 3 meters (10 feet) 99 percent of the time. WAAS is handy when landing a fully loaded 757 in dense fog, but most motorcyclists somehow manage to find their way using regular GPS units.

I’m sitting at 45°26′11.98″N by 73°50′05.95″W and, unless you’re remarkably clever, these coordinates tell you very little. By itself GPS isn’t much help, therefore a very detailed map on which latitude and longitude have been accurately plotted is also required. The concept of longitude (pole to pole) and latitude (the distance measured parallel to the equator) has been known since the Hellenistic era in ancient Alexandria, but the solution to measuring longitude wasn’t achieved until the invention of highly accurate watches (chronometers). The core secret to modern GPS is the use of astoundingly precise atomic clocks in satellites to measure both time and distance. The rest is simply the application of triangulation—the same method the ancient Egyptians used for surveying and mapmaking—but calculated at computer speeds. (GPS units require a minimum of three satellites to be “visible” to perform basic longitude/latitude placement, and four satellites are required to measure elevation. The GPS unit becomes the “fixed object” in the equation and the extra satellite is used for error checking the measurements.)

Landstat satellites, the same ones that emit microwave frequencies for GPS units, also are equipped with cameras that operate at a normal optical resolution of 100 meters for each pixel (a 1024 pixel screen width equals 63.6 miles). The new WorldView-1 satellites can focus down to resolutions as small as 2 inches, but since it takes quite a few pixels to form an image, Orwellians shouldn’t worry about being spotted where and with whom they shouldn’t be. Besides, most of the close-up images displayed on our computers aren’t from satellites, but from high-altitude aerial photographs. Individual photos—both satellite and aerial—taken at different altitudes and often during different seasons is what gives these computer-generated images their patchwork appearance and allows software to create that dramatic zoom-in effect. These carefully scaled photos and a wealth of spatial information, including points with assigned longitude and latitude coordinates, are then stored in Geographic Information System (GIS) databases.

Digital mapping—how it’s done

This aerial-photo mosaic of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec clearly shows the extent of various images and that they were taken at different times. Scaling and stitching individual photos into composite images and aligning them with composite images of different resolutions is one of the most demanding tasks of GIS mapping work.

There are only two primary sources in the world for commercially available digital mapping services. All digital computer maps on the Internet and all the popular mapping programs for personal computers and GPS units are compiled from the GIS databases of Tele Atlas and/or Navteq. To acquire a deeper understanding of how digital mapping is created, I hopped on the bike and rode to the North American offices of Tele Atlas in Lebanon, New Hampshire.

Just as important cities are photographed in higher resolution than rural areas, I learn the same is true for data storage of validated longitude/latitude reference points. In a city, these validated reference points can be as dense as every few feet, but on a straight rural road the stored reference points might only be for intersections or junctions. (Validated means an actual on-the-ground precise GPS reading accompanied by accurate data relating to it—for example, the center of a highway intersection.) The GPS software takes a precise coordinate, calculates it against verified reference points in the GIS database, and then extrapolates its position relative to stored data such as image overlays (graphic maps and aerial photos). The closer the coordinate reading is to verified reference points, the more accurately it can be placed on a map. Although a GPS coordinate reading is accurate to within a few yards, the preciseness of its placement on a displayed map or photograph depends upon the information in the database being used.

Data that’s associated with a given reference point can be practically endless, but often includes a street name, mailing address, road details (direction of traffic, road surface, traffic signals and more) and any points of interest (parks, public buildings, tourist attractions, service stations, hotels, restaurants, golf courses, commercial businesses, etc.). Combined with maps and photo images, mapping programs are approaching a state of virtual reality and soon you’ll even be able to take a motorcycle tour from the comfort of your own home.

Tele Atlas measures data in terabytes. (One terabyte equals 1,000 gigabytes.) Its North American computer is the second largest on the East Coast. But the world is a very big place, and that which is not entered into the database remains invisible, unknown, and uncharted. Anything below the boundaries of image resolution remains unseen. The Age of Exploration is not dead. There are still dragons out there… somewhere.

Kenzo developed the routes for several of the Harley-Davidson “Great Roads” maps, numerous official rally maps, and commercially published touring maps from Texas to New England.