Uly’s Gold

Shining in its element

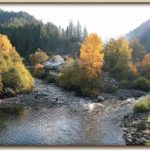

Winding through the canyon of the North Yuba, the lateness of the season and the way it plays out in practical terms at 3,000 feet up in the Sierra Nevada is suddenly a factor. This time of year the sun swings low across the southern sky and there are now places in the canyon where it no longer penetrates and there are sudden patches of pavement that have retained the chilly dews and damps of the night before. These patches usually occur midway through a curve where the canyon’s orientation to the light shifts abruptly and plunges the road into deep shadows. It’s something to consider in speeding into corners, but the Ulysses is not the least bit put off its game by these or any of the other obvious indications that it’s too late in the year to be flogging a sportbike up here in the mountains. Even so, I make a mental note not to ride back down through the canyon too early in the morning when these dews and damps will be textbook black ice.

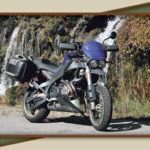

Me and Uly are taking advantage of a warm spell to get in a couple days of “adventure sportbike” travel, the professed purpose of the XB12X, and heading up to the more isolated reaches of the Gold Country to do a little prospecting. It’s not the yellow we’re after, though, it’s the pure fun and escape of riding challenging roads in remote unpopulated areas with no particular itinerary. I call it prospecting, but the more common term for this manner of midweek getaway is probably “screwing off.”

It’s a spur-of-the-moment notion brought on by the optimistic weather forecast that proposes temperatures approaching 80 degrees in the valley and 70 at higher elevations even as winter’s getting set to drop the curtain on the riding season in the high country. The Ulysses is a spur-of-the-moment breed of adventurer owing largely to the ease with which you can stow a whole mess of gear in the bike’s saddlebags without much fuss. The capacity of the bags is astounding, surpassing even the capacity of dedicated touring machines, and it takes all of about 15 minutes to load clothes, an assortment of gloves and layers of riding gear, tools, cameras and a cooler into the bags. Little organization is required, and since the bags snap easily off the bike and carry like suitcases, no liner bags are called for, or even much attention to how things get stuffed inside. It feels a lot like running away from home, and you’re already packed and committed by the time you start having second thoughts about the caper.

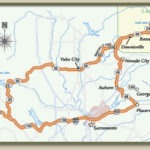

Avoiding freeways as much as practicable, we ride the Highway 29 roller coaster east over the Mayacamas Mountains and speed across the Sacramento Valley on Highway 20 and up into the foothills of the Gold Country on the old Marysville Road with a general destination of the Lost Sierra, with the general objective of getting lost in it all.

Land of the lost

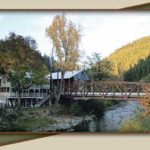

The Lost Sierra is the term that describes the relatively inaccessible and thus largely bypassed northernmost region of the Mother Lode. Some sources claim the name dates to the Gold Rush, but I’ve found the likelier origin to be a National Geographic article from the early ’70s when the area was being rediscovered by back-to-the-land hippies. Either way it’s an apt description. Getting into the area requires climbing up through the precipitous canyon of the North Yuba, and it’s a magnificent passage, tight and twisty and scenic, that opens up abruptly upon a bowl in the mountains. There sits Downieville, hunkered down in that pocket and vined around the confluence of the Downie River and the North Fork of the Yuba River—which gave the town its original name of The Forks in 1849.

The place is almost surreally quaint and picturesque, with a main street shaded by massive old black locust trees and fronted by buildings dating to the 1850s. A single-lane bridge remains the only egress east out of Downieville heading up into the higher elevations and the even more lost extremities of the Gold Country.

Downieville’s become a bit more discovered than it was when I first started riding up here back in the ’80s. Back then it was truly off the beaten path, its Gold Rush-era buildings and atmosphere remaining virtually undisturbed and intact. These days the local businesses have become gentrified somewhat, which had to happen sooner or later, but the town continues to exude a rough-and-tumble gold camp aura, and few gold camps were rougher. (The locals even lynched a woman in 1851—the only such occurrence in the state’s history.)

And few camps were more susceptible to the twin perils of fire and flood, which routinely ravaged the town in the early days, but so rich were the deposits of gold, both in the river beds and in the hard rock of the surrounding mountains, that fortune seekers continued to pour in despite the remoteness and reputation, and by the mid-1850s, Downieville was the fifth largest settlement in all of California.

It’s late in the day when we arrive, and the sun’s already playing coy, ducking below a peak and spreading cold shadows over the town, and I pull into the Riverside Inn.

The modest gentrification the town has undergone is immediately apparent here. I stayed at the Riverside once before, about 15 years ago, when during a similar late-season ramble I camped along the river about 10 miles above Downieville and got caught in a winter storm that drenched my camp and myself with freezing rain and caused rockslides in the canyon of the North Yuba. I managed to ride half-frozen into town and got a room at the Riverside—a motel situated right on the bank of the Downie River. It was a pretty funky place back then, but it had the attraction of a covered storage area beneath the level of the rooms where I could stash my bike to dry out. The place was built in 1948, and had not been renovated since. The furnishings were postwar modern and thus cool, but they were also worn out.

That’s changed dramatically. The Inn is currently owned by Mike and Nancy Carnahan, who bought it in 2000 and have lovingly renovated it, adding private balconies out over the river and furnishing all rooms with homey antiques and fat beds. The Carnahans also happen to be bikers, and when I park Uly in the covered storage area like before, it’s stabled in the company of a late-model Ultra Classic and an ’83 FXR. They’re gracious hosts, the Carnahans, who attend to the smallest details and comforts of their guests, and that includes providing a phone booth on the deck outside that offers free long-distance phone calls— this in response to the utter absence of cell phone reception in the region.

Here we take the Gold The Carnahans also provide a free breakfast which I take advantage of the next morning, carbo-loading on bagels for the chilly ride ahead. A clear night has guaranteed that any lingering warmth of the previous day is long gone and the sun’s taking its sweet time clocking in. The highway east from Downieville climbs almost imperceptibly, but climb it does, and in the dozen miles to the next historic vestige of the gold era, Sierra City, the elevation has risen to 4,200 feet. And it keeps climbing.

A few miles past Sierra City at 5,400 feet is the wide-spot burg of Bassetts Station, and it’s appropriately named since it consists pretty much of a gas station. That wasn’t always the case, and the place started as a mountain resort back in 1871, proceeding from there to serve as a stage stop and lumber camp among other things, and to be fair the gas station also has a quaint café and country store—but it’s the gas you’ll appreciate most at this far-flung outpost since it’s the last you’ll find for a good distance up the divide.

Lake Road cutoff and head up towards the Lakes Basin at the crest of the Sierra Nevadas. And up we go, climbing hard past the warning sign that says, in effect, “Watch your ass up here, pilgrim. Weather happens in a hurry,” and around a sharp bend to the sudden scenic explosion of the Sierra Buttes and a handy scenic overlook. This spectacular 8,600-foot massif is the most underappreciated such formation I know of. Not as awesome as the Tetons, but certainly right up there with the Sawtooth, the Sierra Buttes have the added allure of being lost in the Lost Sierra, and as a result nobody much goes there, and Uly and me have the whole soul-stirring vista to ourselves this morning.

The road on from the overlook remains deserted and the pavement immaculate and given to satisfying sweepers, which puts Uly in a spunky mood, and it goes from packhorse to quarter horse instinctively. The bike also has heated grips which suddenly seem like just the thing. I push the switch by the handgrip to the “high” position and wait for the warmth. And wait. And… bummer, they won’t heat up.

That’s the occasional downside of riding a test bike that may have received God-only-knows-what abuse at the hands of previous testers. It’s a minor annoyance, though. I’ve got warm gloves and liners, and the bike’s handguards provide decent wind protection, and on top of that the heat from the motor keeps the seat sufficiently warm to keep things comfortable on the climb.

Up in the Basin

The Lakes Basin is a collection of pristine alpine lakes situated high atop the spine of the Sierra Nevada, and the jewel of the collection is Gold Lake, so named as the result of an 1850 midwinter episode wherein a half-frozen prospector struggled into Downieville with tales of solid gold boulders in a lake up high. This wasn’t that lake, but it seemed the likeliest candidate once the spring thaw came, and hordes of gold-seekers trekked upcountry in search of the lode. In time it was the Sierra Buttes that proved up the real bonanza, and the imposing massif remains to this day honeycombed with mineshafts.

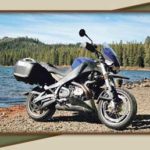

Gold Lake proved up a bonanza of trout, though, and there’s a trio of fisherman there when me and Uly arrive, but they don’t stay long, and once again it’s just me and the machine in a place of world-class natural beauty. Naturally, Uly wants its picture taken lakeside, and puts on its dual-purpose persona for the occasion, roosting up beach gravel and settling at the water’s edge. I take a few snaps, and while I’m at it a stiff wind kicks up over the lake and it’s a cold one. It’s also an unsubtle reminder that conditions at 6,500 feet can turn quicker than a hand of blackjack this time of year. The sky couldn’t be bluer, but the wind is getting fiercer and we descend, heading back to Bassetts Station to get fuel for both of us.

Up the Divide

With no particular place to be, me and Uly cruise back down Highway 49 without a plan or destination. Just riding. Just jamming down the curlicues of the canyons heading south, where things are reputed to be warmer. For the first 50 miles it’s the same road we came up but we’re not really retracing our steps since every mountain road is actually two roads, each direction utterly distinct in both scenic and riding experience. And then we continue down 49 past Nevada City to Auburn, and the periphery of the Sacramento sprawl. It’s a brush with chain-franchise civilization and it’s a sigh of relief when we get through the traffic and start the steep dive down the gorge of the Middle Fork of the American River.

Quick hard switchbacks down, knowing with each flick and lean that there’s going to be a corresponding curve waiting on the other side and stepping up to the rugged plateau between the middle and south forks of the American. This is the Georgetown Divide, and it’s been called that since the Gold Rush when this rugged wedge of the Mother Lode brought forth fabulous amounts of the metal. The principal city of the region at the time was Georgetown, but like Downieville, its fortunes have faded considerably, and like Downieville, its cul-de-sac location out on Highway 193 away from the 49 tourist corridor and on the way to nowhere in particular has left it with a lost-in-time quality.

Georgetown remains a true oddity among Gold Rush towns in that it represented in its heyday the first concerted effort at civic planning, and the vestiges of that experiment endure. When the original canvas-and-log gold camp burned to the ground, as they did with disturbing frequency, the inhabitants used the opportunity to lay out a grand town plan that envisioned a metropolis of substance and regional prominence. That bright promise never amounted to much, but as a result the town sports a grand main street 100 feet wide. These days that grandeur just comes off as odd, with a row of parking spaces down the center even though nobody much parks anywhere downtown, and there’s the appearance of vehicles just abandoned in the street.

This is another town I haven’t visited in a number of years, and what I remember best of it is the Georgetown Hotel, a popular biker bar in these parts and a place with a history in every sense of the word. Back then the hotel was in a marvelously run-down state, exuding history, and now I’m delighted to discover it has somehow bucked the gentrification trends of the Gold Country and retained its dilapidated charm. And it has rooms available, and I’m looking for lodging since the sun’s going down and the only options from here are down the other side of the Divide in Placerville, which is beginning to feel the encroachment of the aforementioned Sacramento sprawl, and me and Uly are doing our damnedest to prolong the sense of high-country isolation and adventure.

I inquire about the rooms, the bartender, a taciturn fellow by the name of Benny, tries to talk me out of the crazy notion. There’s a modern motel right up the road, he suggests. Here you get no phone, no television, and the one room with its own bathroom is right above the bar, and the bar might get rowdy and stay open late. Still interested?

More than ever. And especially because it’s also noted that this place is allegedly haunted. It even has an official certificate to that effect issued by an official psychic who specializes in these things. It’s also an easy matter to register, since the registration desk is, in fact, the bar, and above the cash register the room keys hang on a pegboard. They’re skeleton keys. Authentic ones, and it’s apparent the locks around here haven’t been changed in over a century.

When I naturally suspect the rooms are maintained merely as a courtesy to overserved barflies, but that proves not to be the case. I check out the room and find it large and clean and furnished with gorgeous antiques—a huge bureau with a beveled vanity mirror and a marvelous old sleigh bed. The price of all this authenticity is $60 for the night, payable on the bar tab.

As it turns out, I’m the only lodger besides Benny the bartender, who happens to live up there, and curious about the whole haunted hotel history, I ask him if he’s ever experienced any ectoplasmic manifestations. At which Benny scowls, dumps my drink and cuts me off. Until, that is, I explain that I’m talking about seeing ghosts and such and not about medical conditions of a personal nature. He tells me that he has. He tells me this in the exact tone of voice you would expect from a taciturn bartender answering the stupid question of a gullible tourist.

That night I’m spooked by the sounds of plumbing even older than the furniture.

The morning finally comes and despite still being up above 2,600 feet, it comes warm enough to ride out early, and I haul Uly’s saddlebags and sundry other gear down from the room, put on a mess of clothes and head out down 193. Before long we plunge into the gorge on the south side of the divide and up to Placerville. For the first time on our trip we get on four lanes for the miles to Sacramento, and me and Uly sigh as civilization and reality rear. We hit the back roads once more at Davis and trace Highway 128, where we can get on a back road once more for the final push back over the Mayacamas and home.

And as we pull into the driveway, the feeling that we haven’t had our fill of adventure yet is almost overwhelming. The weather’s fine and there’s still daylight and Uly says: “What are we stopping for?”

And I respond: “We have to unload the sleigh bed.”