From racing buddies to drag-race champions to team owners to aftermarket powerhouses to industry legends, Terry Vance and Byron Hines have achieved a lot – and are still at it! Here’s how it all came together…

Words by Mitch Boehm

Photos supplied by Vance & Hines

In all of motorcycling, with the possible exception of William S. Harley and the Davidson brothers, there is perhaps no better example of the term partnership than Terry Vance and Byron Hines.

The duo have been friends for 50 years and business partners for more than 40, and through these many decades have generated what can only be described as monumental achievements in both motorcycle racing and business. There are the ET/speed records, race wins and national championships in professional Pro Stock and Top Fuel drag racing; the race wins and championships in AMA and World Superbike competition; and during all that, the amazing growth, heft and scope of the Vance & Hines aftermarket performance business, which continues to this day.

It’s a company that has always put its money where its mouth is, letting its performance on the track dictate its marketing and sales efforts – not the other way around. The motto no brag, just fact comes to mind when you think of these guys. The drag racing team’s domination in NHRA Pro Stock competition, with Byron’s sons Matt and Andrew’s Pro Stock championships bookending the 14 titles and 27 NHRA event wins nabbed by Terry and Byron years ago (along with all the private teams who’ve won using V&H engines and technology), highlight the power, savvy, value and longevity of the organization. Then there’s the team’s highly successful affiliations in the ’90s with factory Yamaha and Ducati in road racing. And while the Vance & Hines guys have struggled trying to make Harley-Davidson’s production-based dirt track engine compete with Indian’s purpose-built racing powerplant, one gets the feeling they’ll close the small gap very soon – especially with the very savvy Ricky Howerton leading the Vance & Hines/Harley-Davidson squad for 2020.

Last year, the duo quietly celebrated 40 years in business, the Vance & Hines entity having been created in late 1979. That’s a serious accomplishment on its own. But with all the Harley-based drag racing and dirt track racing development currently happening at the firm’s Indianapolis, Indiana, race shop, and all the new-product development being done on the aftermarket side at the company’s Santa Fe Springs, California HQ, it’s pretty easy to get the feeling Terry and Byron and crew are simply gearing up for another forty.

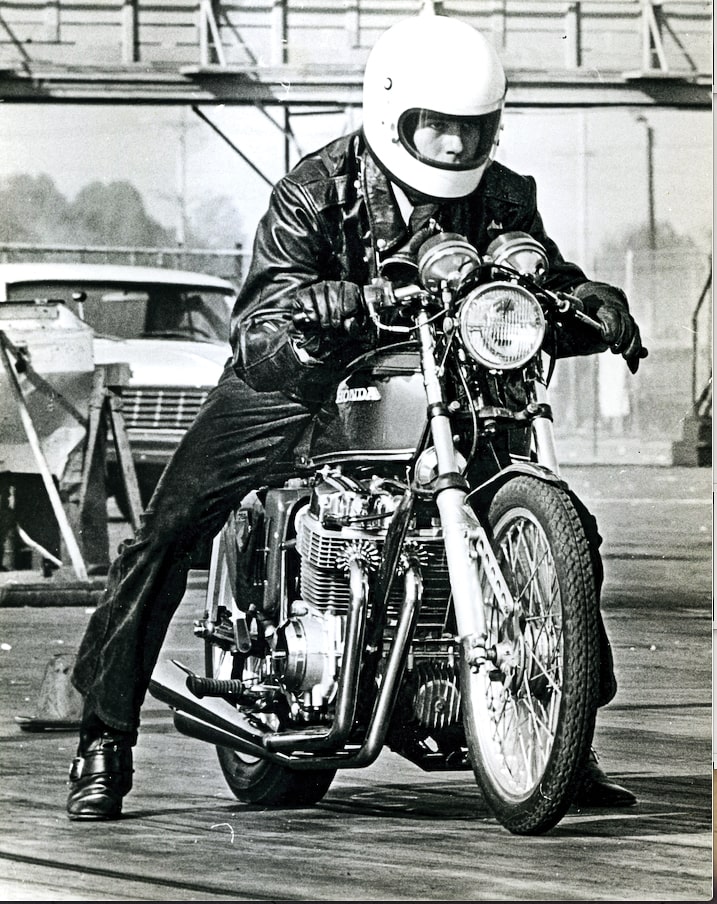

So when and where did this unique and highly successful partnership actually begin? At a drag strip, of course – Southern California’s Lions Drag Strip in early ’71, to be precise. Lions, which opened in ’55 with support from the local Lions Club to help keep kids off the streets and was a hotbed of automobile and motorcycle drags until it was forced to shut down due to encroaching development in ’72, featured thick, oxygenated ocean air – and thusly fast ETs (elapsed times) and top speeds – thanks to its location in Wilmington, near the port of Los Angeles. Terry and Byron, both from the South Bay area, raced at Lions in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Byron on a Suzuki X6 Hustler and, later, a Honda CB750, and Terry on his dad’s 750 Four (and, later, his own CB750). Although both were bracket racing in the late ’60s, the two wouldn’t meet until ’71 after Byron returned from a two-year stint in Vietnam, where he worked as a helicopter ordinance and munitions tech.

Growing up in Southern California, it’s not a surprise the pair got into motorcycles at early ages. “My first bike was a Taco minibike,” Vance told us, “which I bought with money – $107, I think – earned from a paper route. The frame was on display in a lawnmower shop, and I bought it and brought it home. My dad was a motorcycle guy and must have felt a little bad for me, so he took a five-horse engine from an edger we had and we shoehorned it into the frame. I lived by the railroad tracks in Lawndale, CA, and every day I’d run home from school and jump on that thing. Owning and riding it taught me a lot, and I rode for hours all over the place, up to Compton and Inglewood, to the Ralph’s supermarket, everywhere. I had motorized transportation at a very young age, and everyone in school thought I was the shit! [Laughs]

Hines’ experiences weren’t too different. “I was born in Nebraska, but we moved to the South Bay area of Los Angeles when I was pretty young,” he says. “We would travel to my Grandma’s farm in Nebraska in the summers. My uncle had a shop there, and somehow I got hooked up with a little minibike frame and a lawnmower engine, which I pieced together and rode all over the place. Later, as a sophomore in high school, I talked my dad into co-signing for a Honda Super 90 from Torrance Honda, and rode that for a couple of years, to school and back especially, because our high school was in a rough area and you didn’t want to be walking home.”

From there things escalated, as they often do in motorcycling, to larger and faster and funner motorcycles. For Byron it was that Suzuki Hustler, a 250cc two-stroke twin that quickly earned a reputation for being a high-performance ‘giant killer’ before Yamaha’s R5 and RD350 wrestled that title away.

“I needed more power than a 90cc Honda single,” Hines told us, “and managed to get an X6 Hustler. My buddy had the Scrambler version with the same engine, and we started hopping them up, porting the cylinders and whatever we could afford to do ourselves. We didn’t have much mechanical training, but they went pretty good. We could do low 14s at Lions, which was pretty fast. We were having some fun, right until I was drafted in ’68 and shipped off to basic training and then Vietnam.”

Hines spent 22 months in Indochina as an aircraft armament repair tech, and remembers the flight to Saigon vividly. “We’re all on this four-engined jet,” he told us, “right out of basic, and I remember hearing over the loudspeaker that we’d just landed on the moon…so it was July of ’69. I was just a kid, had just graduated from high school, didn’t really know anything. It all happened so quickly for me, and it wasn’t until I came back that I sorta saw how crazy things had gotten back here. But yeah, that definitely took me away from bikes for a while.”

While Hines was off repairing (and probably modifying) helicopter machine guns, his soon-to-be friend and business partner Vance was riding and racing and getting faster by the weekend at the local dragstrips. Early on he was ‘borrowing’ his dad’s bikes, and doing a not-totally-successful job of keeping that information from his dad.

“One night at dinner,” Vance says, “my dad sorta looked at me deadpan and said something like, ‘Terry…my CB750 seems to have developed a head-gasket leak just sitting in the garage … know anything about that?’ He knew what was going on but was ok with it.

“At the time I was just out of high school, just a smart-ass kid going to the track to have fun with his streetbike. It didn’t cost much to race, and it was fun. Heck, I didn’t have any money anyway! My goal was to do something fun with bikes, and something cheap. Just another dragstrip-junkie kid in the South Bay. There were three or four tracks in the area, Lions, Orange County, Fontana and Irwindale. It was sweet. I could make a couple hundred bucks on the weekend, and that would last me all week. All you needed was a van and a bike. There was a lot of sitting around BSing, but I learned a lot – how to change cams and exhaust, carburation, all of that stuff. It was the best learning experience you could have, really. I was fortunate.”

Hines was discharged and returned to U.S. soil in early ’71, and immediately went to the local Honda dealer to buy the machine everyone had been talking about for two years – the CB750.

“I’d been reading all about them but had never seen one,” Hines says, “so I went to the local dealer and bought one. Didn’t test ride it, had never even seen it, just wanted a red one. It’s funny…I was seventh in line that day to take delivery of a 750 Honda. They were taking them out of the crate, assembling them and they were flying out the door. Salesman asked me, ‘don’t you want to ride it?’ and I said, ‘Nope, I’ll just ride it home.’ And I did. And that’s where things picked up again for me on two wheels.”

Hines rode that Honda just about every day, and one afternoon ran into a guy with a Kawasaki H2 – the company’s notorious 750cc two-stroke. “He pulls up next to me over by LAX on those empty streets by the beach,” Hines remembers, “and says ‘let’s go!’ And he whipped my ass. We raced about 10 times, and he won nine of them. I said to myself, ‘I’m gonna need some more power,’ and headed down to Torrance Honda to get a cam or something. One of the guys there asks me, ‘Looking for a cam for that thing? Try Russ Collins; he used to be the service manager here, and he’s got his own place nearby hopping up Honda 750s.’

“So I go see this Russ Collins guy, and he sells me a cam and a set of pistons… 836cc or something like that. I install everything, get it running and then drive by his shop a week later for some plugs. He sees me and the bike and asks who did the work. I tell him I did it. He starts looking at it closely, looking for leaks, and doesn’t see any. So I buy my plugs, and he asks me, ‘Looking for work?’ I tell him I just got out of the service, and he says he needs a mechanic, that it’s just him at the shop doing all the work, and did I want a job. So that’s how it happened. I’m pretty sure I was Russ Collins’ first hire.”

The work was part-time at first, with Hines doing basic stuff such as lacing wheels, installing pipes and jetting carburetors. But as the shop got busier as the CB750s continued flying out of showrooms onto the streets, and with so much extra performance available from the reliable four-cylinder machine, Hines got more involved in engine work, learning through experience.

“One evening we went to the track and I had Russ ride my bike,” Hines says. “Got in the low 12s, which was pretty fast. Then I rode it, and went 12.12. I get back to the truck and tell him, and he doesn’t believe me. ‘Show me that ticket,’ he says, and I show him, and he’s like ‘Son of a bitch.’ Guess he had the record at the time for Honda CB750s at 12.18! [Laughs]

“We were starting to get really busy at that time, especially with our bikes being so fast at the track,” Hines remembers. “Russ would take stock headers and build 4-into-1 systems, which worked really well. But they were a bitch to make…all hand-made, one by one, all that cutting and welding. Once he saw the potential of that market he found a tube bender, which made doing Honda pipes a lot easier – and profitable, too. So much business at the time.”

Little did the pair know, things were about to change in a very big way.

“I met Byron at the track,” Vance says. “He was working for Russ Collins, and just out of the army and Vietnam. I’d gotten my own CB750 by that point and was riding it and also some other people’s bikes. Byron and I got to be friendly. After a while Russ asked me to ride his bikes, ones Byron was building.

“Like us, Terry was at the track all the time,” Hines remembers, “winning brackets, going fast. I could tell he was good. He’d ride anything; his CB750, Mike Tedder’s Hondas, whatever. One night Russ said to me, ‘Why not put that Vance kid on your bike?’ So I talked Terry into it, and right away he was two or three tenths faster than me! I started helping him work on his bike, and we started having some fun. We’d go the track, then go out riding, end up riding all night. This was before we both got married. Good times, lots of fun.”

Eventually, Vance joined Hines at Collins’ shop, which now had a name: RC Engineering. The trio meshed, things were busy, and business was good.

“Byron did motors and bikes, and I was helping take care of Russ’ business,” remembers Vance. “Great stuff, great fun, and a great situation… But working there was not an easy decision for me. I had just gotten married and had a really good union job at a print shop making good money – $1200 a month. Russ had offered me about 30% of that, so when I quit the printing press job no one could believe it! Problem was, I hated it. I wanted to do something with motorcycles, something I loved. That’s why, when I talk to kids these days, I tell them to do something they’re passionate about. Otherwise they’re just wasting their time.

“Working with Byron and Russ was not like a job,” Vance adds. “We’d develop stuff, race with it, do well, and customers would want those parts, which Byron was making. I was keeping track of orders and doing sales, and my drawers were always filled with rods and pistons. This was ’72, I was 19 or 20, and learning a lot about business. It was big fun. Our lives were consumed with going fast, making parts, dealing with customers. We weren’t making much money personally, but business was good and we were loving it. There were three of us in the beginning, and it grew to 50 or so by the late ’70s.”

It’s a partnership.

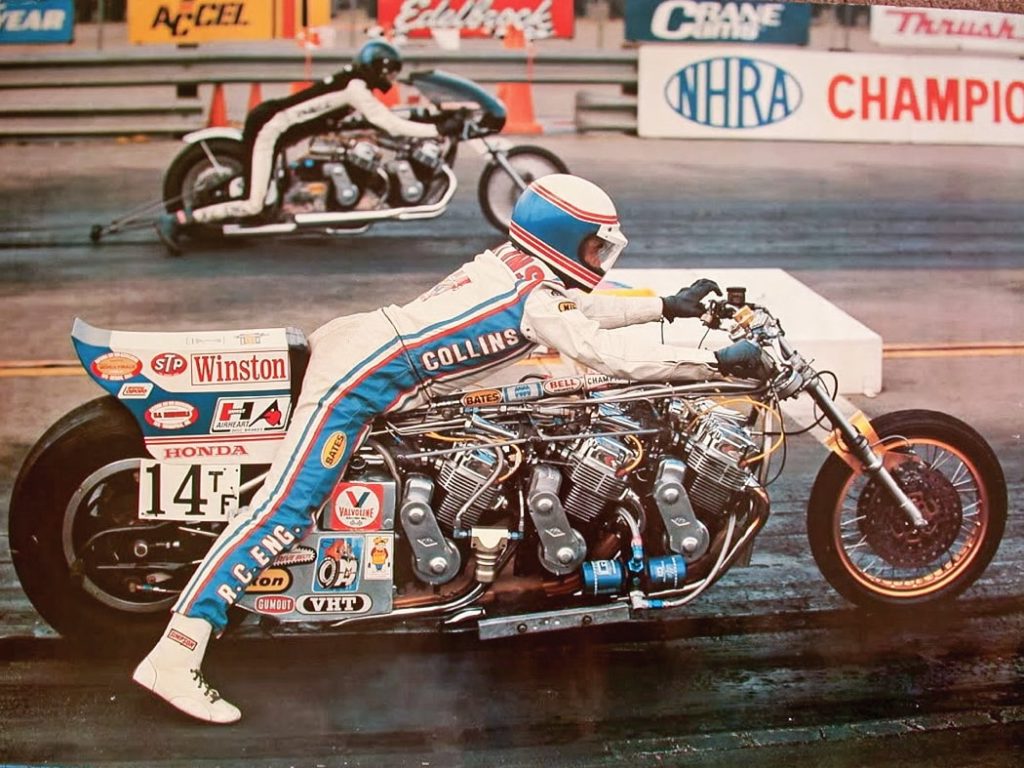

A lot of amazing stuff happened in motorcycling during those 1970s, at RC Engineering and in the industry as a whole. The two-wheeled Japanese invasion of the ’60s, led by Honda’s ‘Nicest People’ campaign, had turned motorcycling into a massive and mainstream activity, and bike sales exploded right along with interest in riding, racing and performance. Along the way, Collins, Hines and Vance sold a lot of parts, ran a lot of races and built some of the wildest drag-racing motorcycles known to man, including the 300-plus horsepower Honda-powered Assassin in ’71, the three-engined Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Top Fueler (named after the famous rail line of the 1800s, and which nearly killed Collins in a crash) in ’73, and the twin-engined Sorcerer in ’77, which set a 7.3-second/199-mph class record that stood for over a decade.

Collins was a big Honda fan during those years, but the Z1 Kawasaki of ’73 and GS750 Suzuki of ’76 opened things up dramatically in terms of overall inline-four performance, on the street and at the racetrack.

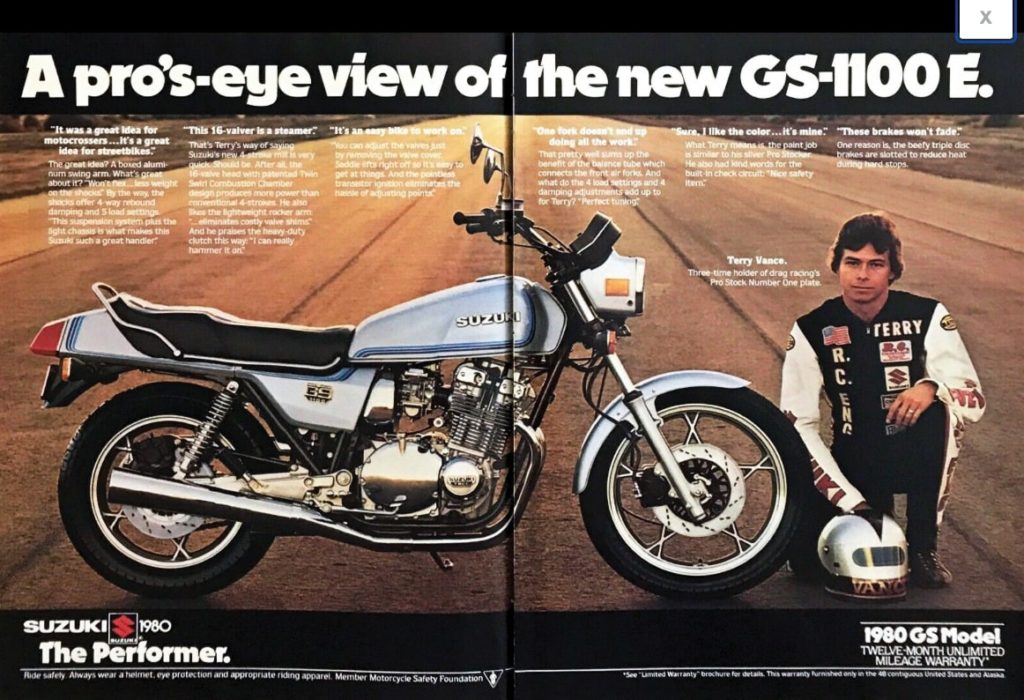

“I remember Terry and I trying to lock down one of the factories for a sponsorship deal in either Pro Stock or Top Fuel,” remembers Hines. “Terry started talking to the guys at Honda, Kawasaki and Suzuki. Kawasaki seemed interested, but would only offer us a bike – no money, and we had to return all the stock parts. Not sure why, but it was not a great deal. A little later Terry met with Gene Trobaugh, a senior guy at Suzuki. The GS750 was just about to debut, I believe, and Gene and Terry put together a really nice deal.”

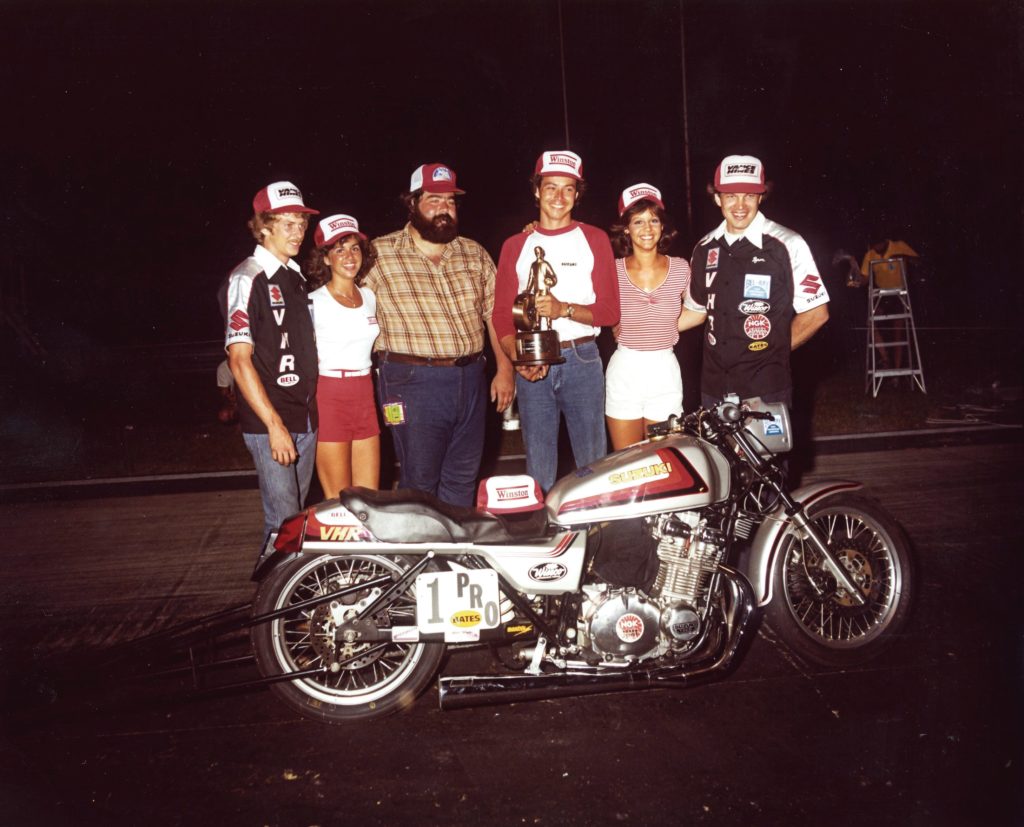

“If it wasn’t for the GS750”, remembers Vance, “I’d be working some parts counter in Inglewood. That’s the bike that made the GS1000 possible, and without the GS1000 I’d have missed my opportunity. Byron and I were racing Z1s and doing well. We won a couple of championships. Suzuki’s Gene Trobaugh had this big-picture vision to radically improve Suzuki’s reputation on the heels of the new bike. We put a plan together, signed a contract and they sent us a bike. When we pulled the crate off, everyone gathered around, as no one had seen a GS before. We started winning pretty quickly, and away we went.”

“Our partnership with Gene and Suzuki was great,” says Hines. “I remember Gene calling one day in maybe late ’78 or early ’79, and saying something like, ‘Hey, I want to show you something’. He comes by and takes me to a non-descript building, opens up a door and there stands two prototypes of Suzuki’s new bike – the sixteen-valve GS1100, with the TSCC heads, which debuted in ’80. I got a chance to completely disassemble the engine to see what was what and get a feel for what was coming in a year’s time, which helped. That was Gene; always on the gas!”

[Sadly, Gene Trobaugh passed away as this story was being written. Condolences to his family, and especially Tom Trobaugh, who’s currently a product-planning manager at Vance & Hines. -Ed.]As their success on Suzukis grew, Terry and Byron began to see a bigger picture in terms of racing and business, and it didn’t exactly mesh with what RC Engineering was doing and where the company was going.

“RC Engineering was a pretty good place to be in the ’70s,” Byron says, “and we were fortunate to have hooked up with Russ early on. But things change, and Terry and I wanted to do different things. We wanted to race for a championship. Russ was into exhibition, showmanship. Just a different mindset, really. We wanted to race and win. He wanted to show up and get appearance money. He was good at that!”

“Russ was flamboyant,” says Vance. “Not our type of guy, really. Byron and I would always talk about doing things differently. He wanted to rent, for instance, and we wanted to own property, put down business roots, do things right, really control our own destiny. And toward the end of the ’70s we saw an opportunity to do our thing.”

That thing was their own company, one they controlled. Once the decision had been made to move on they gave Collins plenty of notice, in Hines’ case three months notice.

“We didn’t want to leave Russ in a bad way,” says Hines, “so I stuck around for a long time, hoping to teach his guys as much as I could. We’d done all this really novel and unique stuff with all the multi-engined drag bikes and all of our racing, and his guys needed to know. Russ had a smokin’ business, but he sorta took his eye off the ball.”

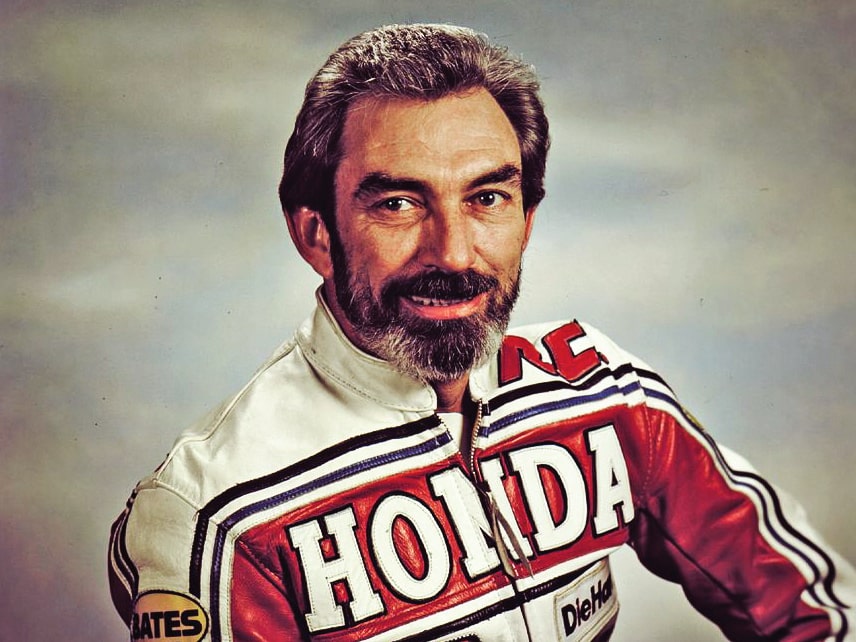

“Letting Byron go was a big mistake on Russ’ part,” says Vance. “He could have locked Byron up. He simply didn’t understand what Byron brought to the table. Byron is brilliant, and not a normal guy. He has an engineering mind, understands math and geometry at a deep level, knows why things work and how to apply them. He’s not a parts changer. He was a golden boy, literally. I’m lucky to know him; he was almost like a big brother figure to me. So smart. And very mature and thoughtful. But Russ didn’t get it. Russ thought he was making everything happen, but really it was Byron. So we walked out the door.

“The plan,” says Vance, “was to take what we knew to the next level. Be professional. Win championships. Establish ourselves. Buy property. Build a business. Put down roots. Treat our employees well. Do things right. It wasn’t easy, for sure. Early on we struggled. But we eventually got to where we wanted to go.”

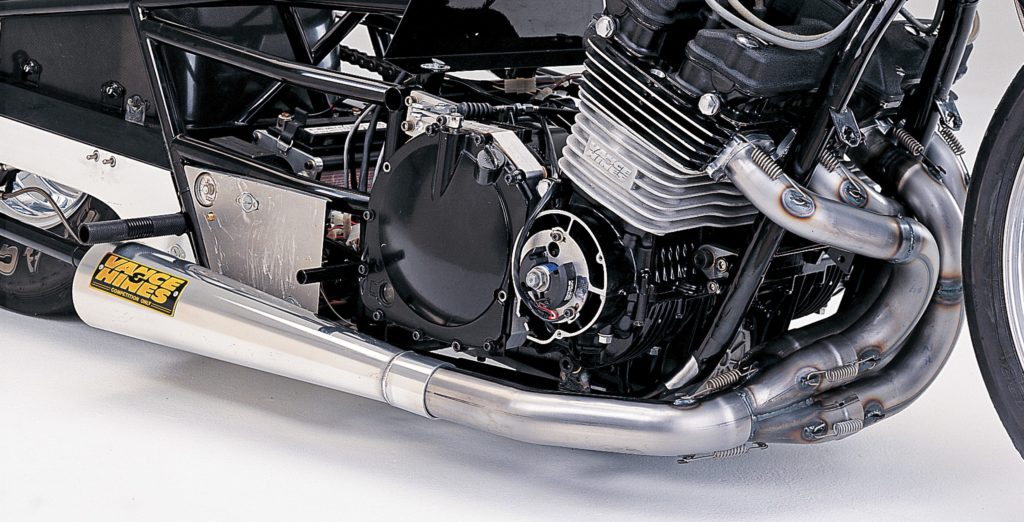

“It was pretty tough at first,” Hines remembers. “We felt like we could make it doing mainly engine building on a local level. I think we did $500 that first month. But that wasn’t gonna cut it. I remember Terry saying something like, ‘We gotta build exhaust pipes, and good ones!’ I was busy building motors and porting heads. But he was right; we needed to expand our offerings. So we found a local pipe bender and got to designing and building pipes. And it worked; we generated a following in high-performance exhausts pretty quickly, and that allowed us to get some cash flowing, which allowed us to borrow some money and hire some good people – some of who are still with us, and others who retired after working for us decades. And things went on from there. We eventually bought property in Santa Fe Springs, and have added more space over the years.”

It’s a partnership.

Vance and Hines rolls off the tongue a lot better than Hines and Vance, so the name of the company was an easy one for the guys. Interestingly, their iconic logo, which has not changed in 40 years, came about pretty easily as well.

“We needed a good logo,” remembers Vance, “so we hired an agency to help us. They brought in a big board one day with a bunch of options on it, and as soon as I saw it I walked over and pointed right at our logo. Bang! That’s the one. Done deal. Just like that. It was perfect, and it has been all these years. We were fortunate to have them helping out, as we were pretty nervous early on. We’d borrowed $50,000 for operating capital, payroll, etc., just to get us going. But having that sort of expertise in the early stages helped.”

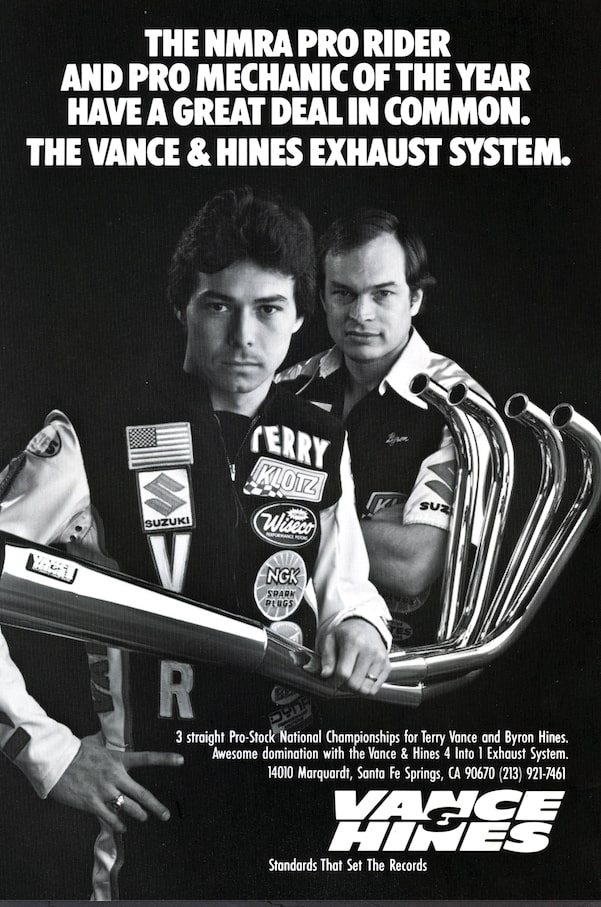

From there the duo and their new company took off, offering high-performance exhaust pipes, engine-building services and more to the general public, and continuing their drag racing efforts that would eventually net the duo, in total, 27 NHRA national wins and 14 national championships before Terry retired from racing in ’88. During the ’80s their 4-into-1 Vance & Hines megaphone exhaust system would become synonymous with street and racetrack performance, while a firm emphasis on quality and customer service would cement them as the high-performance aftermarket company in the industry. The company’s motto of “If there’s a problem, it’s not a problem!” isn’t bluster.

“While it was tough early,” Vance says, “things improved pretty fast for us. I think we had maybe 60 employees in our second or third year, so we passed the RC Engineering guys pretty quickly.” Growth through the ’80s and ’90s was near stratospheric, with the company having 600-plus employees in the mid 2000s. “Byron and I are really proud of the fact that we had so many long-time employees, some of whom worked with us their entire working lives and were then able to retire. That’s a pride point for me.”

While business rolled along, road racing got added to the mix. The company had dabbled in the sport during the ’80s, supplying various teams and winning four consecutive WERA 24-hour endurance events at Willow Springs [with this author riding on the V&H team in three of those efforts]. But in the ’90s things got serious, with Vance & Hines running Yamaha’s official AMA Pro road race team for several years from 1990 on. They did exceptionally well, too, winning the 1990 Daytona 200 (Dave Sadowski), 1991 AMA Superbike title (Thomas Stevens), 1993 Daytona 200 (Eddie Lawson), 1994 600 Supersport title (Jamie James) and 1995 750 Supersport title (Tom Kipp). In ’97 V&H took over Ducati’s factory roadracing efforts, a highlight being double wins scored by Ben Bostrom and Anthony Gobert in the prestigious Laguna Seca World Superbike event in ’99.

A few years before those impressive wins at Laguna, Terry had come to Byron with an interesting idea…to get into the V-Twin – and primarily Harley-Davidson – exhaust and performance market.

“Terry said we needed to start doing Harley-Davidson stuff,” recalls Hines, “and it was something we’d been hearing from Terry’s friend Ray Worth, who was a Harley dealer. I was like, ‘Get out of here! Why would we do that?’ [Laughs.] Of course, Terry was exactly right, and it wasn’t long before we were overwhelmed with orders. That’s all on Terry. He’s always ahead of the curve, always switched on. Russ saw it early on, and it’s just grown over the years. Terry’s always had a good grasp of the bigger picture, motorcycle stuff, obviously, but also in the business world.”

Did Vance see the great sporting motorcycle crash of the late 2000s – which would have crippled a sportbike-focused company like Vance & Hines – in his crystal ball? Not likely. But there’s no doubt he recognized the mammoth strength and market impact of Harley-Davidson and its brand, and how that would affect Vance & Hines: the new-bike sales and large-displacement market domination, of course, but also the baby-boomer demographics involved in all of this as well as the fact that Harley owners would very likely respond to his company’s made-in-America ethos and performance heritage.

They did, and continue to do so, in big numbers.

“Terry and Byron started and built the company on racing,” says Vance & Hines President Mike Kennedy, who spent 28 years at Harley-Davidson and who knows what makes his new company – and its products – tick. “And the products today are all about leveraging the team’s experiences from the track into great products for riders. We make exhaust systems for just about every motorcycle brand on the planet, including, of course, Harley-Davidson. We also make electronic fuel-management and air intake products, and we make it all in Santa Fe Springs, California, where Terry and Byron started the company. Vance & Hines products are known for being of the very highest quality, and that’s because Terry and Byron infused those high expectations into what we build here in our factory.”

Harley-Davidson itself recognized the duo’s accomplishments, brand strength, professionalism and ability to get stuff done, and hired them in 2000 to run Harley’s drag racing team under its Screamin’ Eagle brand.

Kennedy, ironically, was involved in that decision back in 1999. “Harley’s drag racing program was struggling and we needed an experienced, expert partner,” he recalls. “We knew of Terry and Byron’s amazing history in drag racing, but we didn’t think they’d be interested in working with us. They’d been welded pretty firmly to the Japanese brands all those years. But when I called Terry and we talked about it, he was very open to the idea, and we eventually got together. What they have been able to accomplish on the track with the Pro Stock program is incredible.”

Still, things did not go well early on, with the team not even able to make a final that first year. But as expected, things improved dramatically, with the team – comprised over the years of riders Andrew Hines, GT Tonglet, Eddie Krawiec, and, more recently, Angelle Sampey – grabbing innumerable wins and 10 championships in the last 16 seasons. A sideline Top Fuel effort with Doug Vancil at the controls also netted a handful impressive championships.

In 2017, Harley-Davidson got back into professional dirt track racing on a factory level with a replacement for its legendary XR750 – the XG750R – and, you guessed it, Vance & Hines running the show. Much like the drag-racing scenario, the first few years have been a struggle, with no wins and just three 3rd-place finishes in the premier AFT Twins class to show for all the work and money invested.

But there were signs of life during the 2019 season, with team riders Sammy Halbert and Jarod Vanderkooi running stronger than ever in AFT Twins, and comeback-kid Dalton Gauthier posting the XG750R’s first-ever twins-class wins with victories at the Sacramento and Springfield Miles in AFT’s new Production Twins class. Those wins earned Gauthier a spot on the 2020 Harley-Davidson/Vance & Hines factory team alongside Vanderkooi and team newcomer – and ex-Grand National Champ – Bryan Smith, who brings his highly experienced crew chief Ricky Howerton to this year’s AFT SuperTwins (which has replaced the AFT Twins class) effort.

“It’s been a learning process, for sure,” admits Hines when asked about the dirt track effort. “We kept hearing ‘more power’, and yet when we did a little testing experiment and ran our bike against the very good Indian FTR on asphalt in straight-line testing, where there’s no wheelspin, the XG was clearly faster. But as soon as you get onto the dirt we lost that advantage. And that’s where Ricky and Bryan come in. They’ve got open minds and experience here, and they’ve already made a big difference. The first thing Ricky said was ‘you’ve got too much power; knock these things down a bit.’ And so he and Bryan have focused on rideability and tractability. Compared to last year’s bike the new one is easier to ride, and that will help. But of course all that means nothing until the racing starts in July. So we’ll see.”

So….Given what we know about the company, and having the clarity of 40 years of V&H effort and achievement in the rear-view mirror, it’d be pretty hard to bet against these guys. Again and again they have figured out the challenge, put their heads down and worked it with skill, common sense and energy until they got where they wanted to be – be it on a twin-engined Honda dragracer in the early ’70s, a just-released Suzuki GS1000 in ’78, launching their new business in ’79, preparing the FZR750 that carried World Champ Eddie Lawson to a Daytona 200 win in ’93, developing the V-rod Pro Stocker in ’01 – or in their ongoing business.

“For us,” says Vance, “success means a lot more than just winning races or championships – or the money. [The company sold to a private equity investment group in 2002 for many times its $70 million annual earnings. Ed.]

“Anyone can win races if they try hard enough and are reasonably talented,” he added. “To us it’s more about doing what we loved, not feeling like we’re working, and accomplishing goals – building a successful business, something enduring, something valuable and worthwhile. What we’ve built with all our employees and partners over the years…yeah, that’s very satisfying. That’s how you really win!”

Again, it’s a partnership. And arguably the best example in all of motorcycling’s aftermarket. We’re thinking William S. Harley and the Davidson brothers would undoubtedly agree.

Great Article about some of my heroes. What bike nut didn’t drool over the RC days. Those things were as exotic as the Batmobile! They and Cook Neilson were what inspired me to want to understand and love motorcycles. Glad to see Mitch still working,educating and reminding me of all the things I’ve spent a lifetime loving.

Excellent article.

Credit where credit is due , an excellent article about the icon(s) that is/are Vance and Hines – much appreciated by this reader – thank you –