This article from former Thunder Press Editor-in-Chief Terry Roorda (2000-2017) was published in the April 2022 30th-anniversary issue. For more great feature stories, please subscribe!

In the year 3022, a research team of paleo-moto archaeologists, which is a thing, have excavated a promising site and stumbled upon a trove of incalculable value. It is no less than the most comprehensive and granularly detailed chronicling of the period that has come to be known in academic circles as the Golden Age of American Motorcycling.

The researchers pore over the find awestruck and agape until, finally, the reverie is broken when a young female intern, more agape than the others, pipes up, “What in hell is a wienie-bite contest?” The question is met with a chorus of knowing chuckles from the rest of the team.

In the year 2005, a beehive of activity is taking place in Scotts Valley, California, because it’s the day before the press deadline and the staff has a book of 200 pages to wrangle to press, and the last-minute details are overwhelming.

The atmosphere is one of frazzled intensity bordering on hysteria when a female intern, more frazzled than the others, breaks the pall, piping up, “Why in hell can’t those people get their shit in on time?” The question is met with a chorus of knowing chuckles from the rest of the team.

“Those people” (of which the Editor-in-Chief was the chief offender) included editors in California, Texas, and New Jersey; Bureau Chiefs in the Northwest, Southwest, Midwest, Southeast, and Northern and Southern California, as well as a dozen columnists writing everything from opinion to regional three-dot gossip, to fiction, to technical, industry, and lifestyle musings. That’s just the tip of the “those people” spear, and it was backed up by a veritable army of inveterate contributors joined by first-timers eager to see their name in a byline.

Every word and photo of that myriad of submissions then endured the dread Editorial Loop – a gauntlet of four copy editors with red pencils and red eyes and anal standards – before it ever reached layout, where the agony really began, including another trip or three through the gauntlet.

Now repeat that scenario twice a month, month after month, year after year, and you get a snapshot of what went into producing three distinct regional renditions of Thunder Press, each with its own cover, masthead, content, and versions of the magazine’s renowned events calendar.

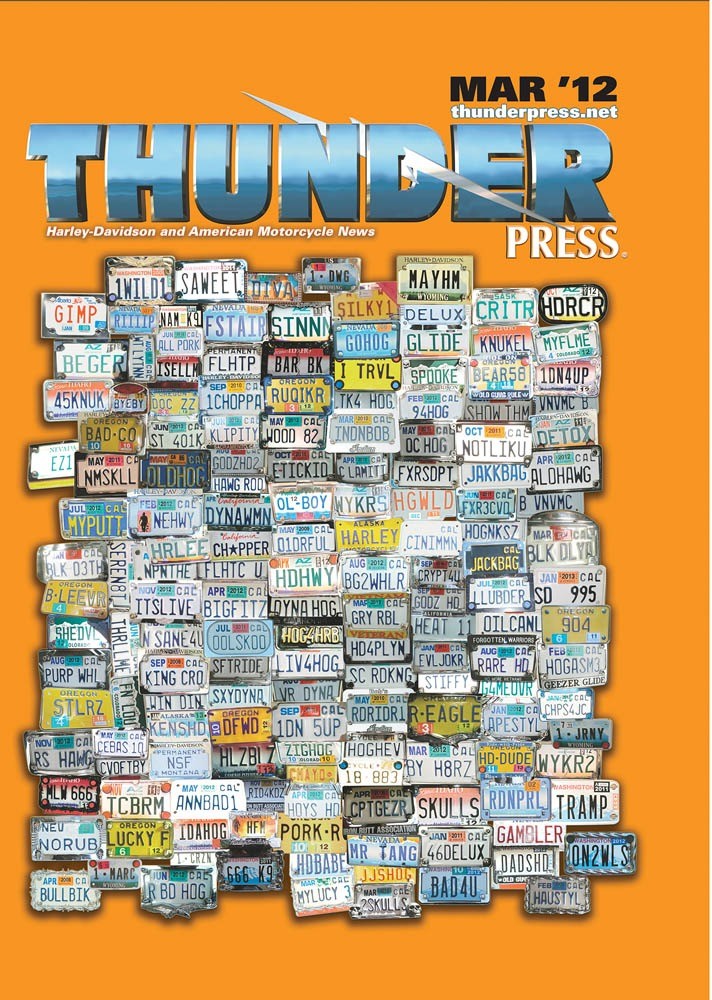

Every year, in addition to the avalanche of usual content, we produced the special issues that the publication was known for, especially the wildly popular license plate covers every March. During the year we compiled hundreds of personalized license plates from all 50 states that were submitted by our readers and augmented by editorial staffers attending events nationwide and snapping photos of any off-beat license plates that caught their fancy. The submissions were filed by state and grouped by the regional edition they represented. They were then painstakingly composed into three clever and colorful collages to adorn the various covers.

Then there was the annual Thunder Press Yearbook, a humorously themed photo portfolio of the editorial, production, and sales personnel, along with a regular rogues’ gallery of all the principal contributors from the previous year (most of whose headshots arrived right at deadline).

But wait … there’s more! Several times annually, Thunder Press produced, entirely in-house, pull-out event maps and guides for major rallies nationwide, from Laughlin to Laconia; from Daytona to Milwaukee; from Las Vegas to Myrtle Beach and Panama Beach. The map was also given expert treatment by the art staff to the many touring travelogues we published, adding life to the sometimes-dry text.

As you can tell by now, the Thunder Press staff had to have deep skill sets and quick reflexes to handle the wide-ranging and often last-minute demands of publication. To that end, everyone in the pressroom was a seasoned pro, and if they weren’t when they first hired on, they sure as hell were by their third or fourth deadline.

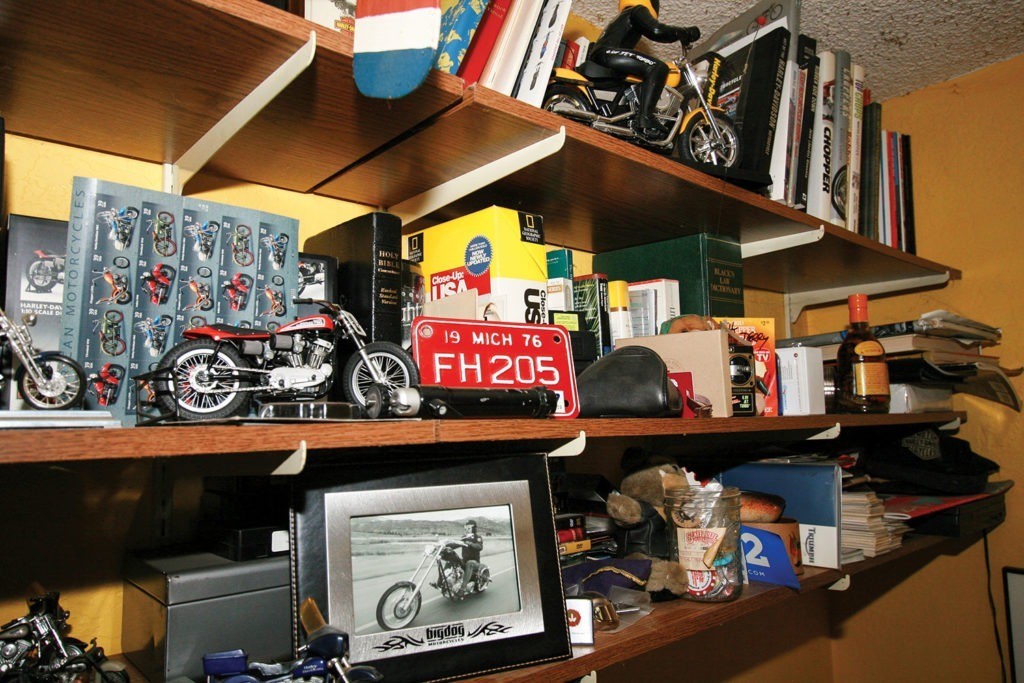

The golden era of Thunder Press came to an end when, in 2010, our corporate overlords in Minnesota – who were poking their noses into our affairs – unceremoniously lowered the boom on our operation. In short order, the offices in our ancestral home of Scotts Valley were shuttered, crated up, and carted away, lock, stock, and archives to Maple Grove, Minnesota. Nearly the entire office staff, some whom had been with the publication since the earliest days, was laid off.

With that, Thunder Press became essentially homeless. Scotts Valley had been a second home for most, a reliable headquarters where the phone calls from contributors, advertisers, and disgruntled readers were answered by knowledgeable, capable, and occasionally surly colleagues.

Its closure left only memories of holiday banquets, picnics, team-building outings, casual post-press cocktails with a few colleagues at the fern bar up the street; all the memories of conviviality and family-like camaraderie and running jokes; all the memories of friendships made, cliques formed, rivalries contested, grudges nursed, and drug deals consummated. And I suspect, as well, some flirtatious activities, though they were kept on the down-low because the Editor-in-Chief would brook no monkey business that he wasn’t a party to. In other words, the whole panoply of human dynamics that can be found in pretty much any small close-knit office setting anywhere.

The years of the Thunder Press diaspora had begun, with all three editors and two remaining Scotts Valley staffers working remotely, submitting their work to a production staff of strangers in a strange land.

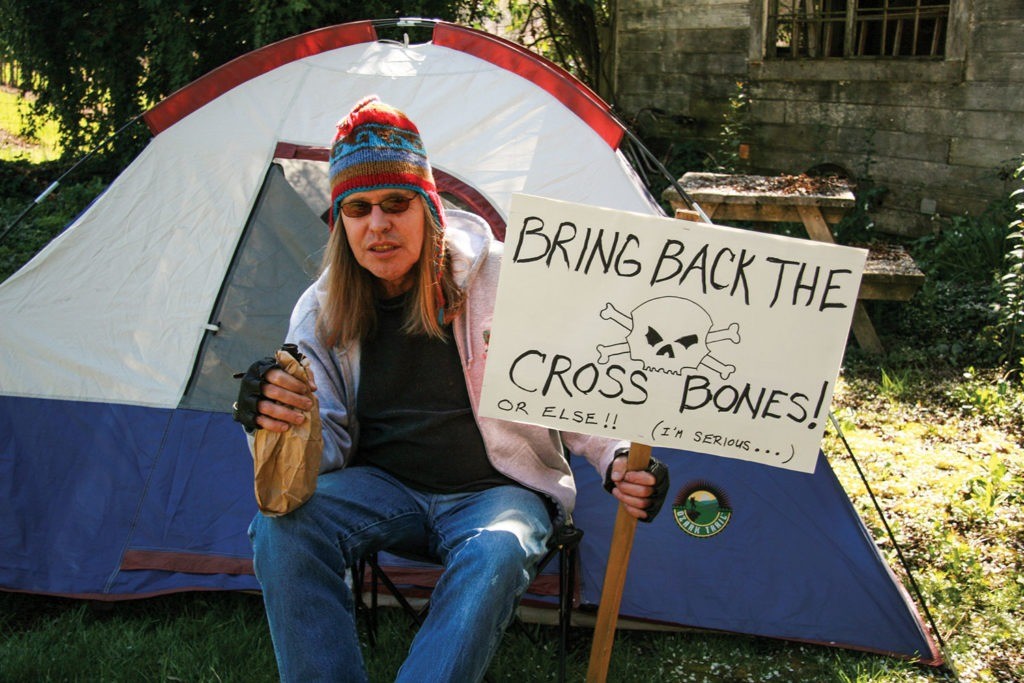

The putative headquarters of the publication became wherever the three editors and a couple of sales people assembled for a brief period: various rented houses in the Black Hills, various hotels in Cincinnati for the V-Twin Expo, and especially in Daytona Beach, where for 10 days a year for a number of years, a Florida shotgun cottage on South Wild Olive Avenue, a block off Main Street, became both headquarters and party central. It was there that, in addition to the editors and sales folk, any Thunder Press contributors and friends of the publication in town for the rally would congregate or just stop by for a tumbler of mescal and a lap dance.

Good times, for sure, but also the busiest days of the year for the editors and writers and photographers who would work their biker buns off furnishing saturation coverage of the countless activities in the area, secure in the knowledge that upon returning home, they’d be staring a fresh press deadline straight in the fangs.

The years of the diaspora continued even as the fabric of Thunder Press unraveled slowly but inexorably, as did the V-Twin industry and biker culture generally, through the end of my 17-year, 408-deadline tenure.

But, as the paleo-moto archaeologists of the distant future would discover, all that time we were amassing no less than the most comprehensive, granularly detailed chronicling of the period that would come to be known as the Golden Age of American Motorcycling.

Though we didn’t know it at the time. All we knew was the all-consuming effort, talent, diligence, and laughter that went into meeting that infernal deadline. And then turning right back around and doing it all again two weeks later. And in all that time, we never missed one.