This article was published in our April 2022 30th-anniversary issue. For more terrific feature stories, please subscribe!

Thirty years ago, at the dawn of this magazine’s life, Harley-Davidson’s first Superbike roadracer had been in development for nearly five years. A number of experienced hands had been involved in the project: Erik Buell, Jerry Branch, Dick O’Brien, Mark Miller, and Don Tilley.

The original concept was to take an XR750 motor and thoroughly revise it with an oversquare bore and stroke and a 1,000cc displacement. Since this motor would essentially be all-new, Buell suggested building a high-tech liquid-cooled V-Twin instead.

At that time, the only liquid-cooled V-Twin in production was Ducati’s recently introduced 851. Buell figured Harley could beat it with a 1,000cc V-Twin.

When Harley CEO Vaughn Beals and engineering chief Mark Tuttle gave the go-ahead, Buell went to work on a two-dimensional engine model. He blocked out a 60-degree, DOHC V-Twin, canting the engine forward five degrees.

“I looked at the Cosworth 2-liter four-cylinder, which made about 300 horsepower,” Buell tells us. “And I thought we could make 140 horsepower with two 500cc cylinders. Cosworth told me making power was all about the airbox having huge volume and getting enough pressure in there.”

Buell’s V-Twin layout then went to Harley engine man Mark Miller, tasked with producing the engine from scratch. As for Buell, he created an aluminum chassis that doubled as the fuel tank to preserve adequate airbox volume where fuel would normally reside. Sadly, the engine that Harley sent to fit in the chassis was in a spec that was grenading during dyno testing, so the bike was never tested.

Considerations on chassis design continued bouncing around between Buell and the Harley factory. As engines were breaking on the dyno, the project fell behind schedule. H-D decided to assign the head work to Roush Performance, known for Ford performance parts. Ultimately, Roush engineer Steve Scheibe was hired by Milwaukee to head the VR project and create a 2nd-generation motor.

Erik Buell thought Cosworth would have been a better choice for engine solutions. “If I was leading the project, that’s what I would have done.” Soon it was common knowledge that Buell and Scheibe didn’t play well together.

“We argued about suspension design, spring rates, steering head angle,” Buell says. “He didn’t like (my) beam frame, the split radiators, or the anti-squat concept.” By this time, Buell was busy developing motorcycles under his own brand.

H-D contracted English builder Harris, which constructed a prototype that was under consideration. Instead, Harley enlisted Mike Eatough, who had worked in the English Armstrong Grand Prix 250 program, and he worked in-house with the factory on the frame. The final chassis did incorporate a steeper steering head angle like Buell wanted, but it used a conventional tank rather than fuel in the frame.

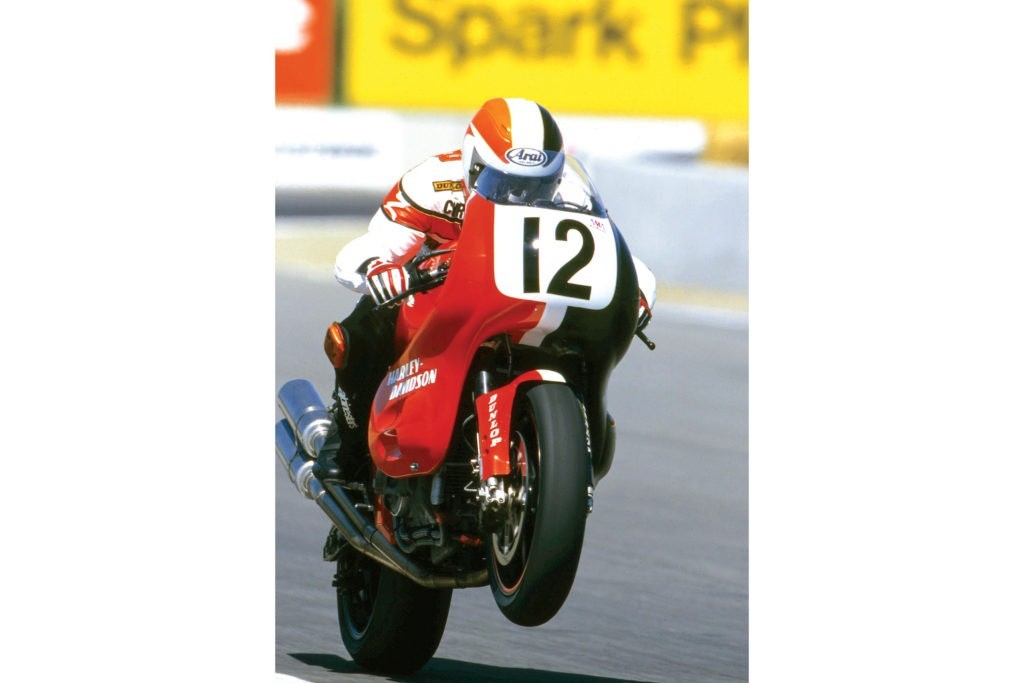

In 1994, following six years of trial-and-error development on the engine and several chassis designs, the VR1000 was finally ready to race. Miguel Duhamel put the VR on the front row for the Mid-Ohio Superbike race, and the Canadian ace diced with the leaders for 14 laps until his shift linkage came adrift.

Duhamel was leading on the last lap at Brainerd, Minnesota, but he dropped back to 4th by the time he crossed the checkers. These front-running performances showed promise for the VR. Scoffing doubters were effectively silenced, Harley fans were enthused, and the Milwaukee team was considerably encouraged.

The following year, Duhamel left the team to ride for Honda, so Harley hired former Grand Prix rider Doug Chandler to replace him.

“That was a pretty bad year for me,” Chandler remembers. “We did a fair bit of testing, but I crashed on the first lap at Daytona and broke my shoulder.” Less than two months later, Chandler would crash again at Laguna Seca, re-injuring the same shoulder.

“But I really enjoyed working with the Harley guys,” Chandler recalls. “There was a lot of enthusiasm for the project, but the bike was down on power.”

Work continued on the VR’s engine and running gear during the off-season. Following Chandler’s complaint of understeer, the steering head was pulled in, embraced by stout magnesium triple clamps holding an Öhlins fork and lighter Marchesini wheels. The 5-speed transmission was replaced by a 6-speed, which was a tight fit.

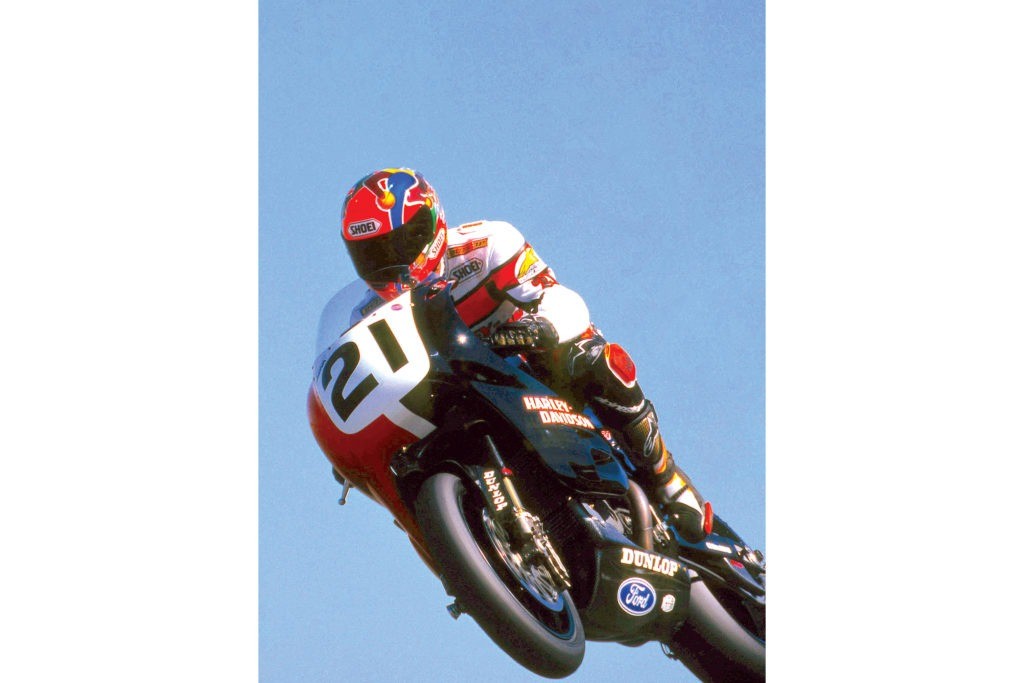

In 1996, the Harley team had Chris Carr and Thomas Wilson in the saddle. Carr, a former AMA Grand National dirt-track champion, surprised everyone, including himself, by putting the VR on the pole at Pomona, California. Unfortunately, he crashed out of the race.

At a rain-soaked Mid-Ohio, Wilson had the Harley in front at the checkered flag. Unfortunately, a crash on the last lap brought out the red flag, which, according to AMA rules, backed up the results by one lap. This handed victory to Pascal Picotte on a Suzuki, and demoted Wilson to 2nd. Still the VR’s best-ever finish.

More disappointment followed in 1997, with few strong results. Carr finished 7th at Loudon, New Hampshire, a position Wilson matched at Brainerd. And at Colorado’s Pikes Peak Raceway, it was Wilson in 9th and Carr in 10th.

In 1998, Harley signed Canadian Pascal Picotte to a two-year contract, but he struggled to race at the front of the pack. He put the VR in 6th place at Willow Springs, California, and 7th at Laguna Seca. Picotte closed out the season with two nice 4th places at Colorado and Las Vegas, but the VR was still down on top speed against its competition.

In 1999, H-D kicked the talent up a notch and hired Scott Russell, former AMA and World Superbike Champion, for a reported $2M. But a bar fight two days before Daytona put Russell in the hospital with facial injuries, causing him to miss Daytona and several more races, and he never came to terms with the VR. Picotte, however, took a strong 3rd at Sears Point, 5th at Mid-Ohio, and 2nd in the season finale in Colorado. Russell, in his best finish, was 10th.

Both riders were back for the 2000 season, but the VR1000 had begun to look like the proverbial dead horse. Daytona ate up a pair of Dunlops after 20 laps, and top-end power was still down. Picotte struggled to finish in 9th, beset with traction problems and an erratic electric-shift mechanism. At Brainerd, he was down 12 mph to the front runners and again finished downfield. In Colorado, Russell was running in the top 10 but retired from the race with engine issues.

It was widely rumored that Russell wouldn’t be asked back on the team for 2001, and the Georgian gave no indication that he had any problem with that, eventually riding a Kawasaki again at Daytona. Picotte was running 7th in the closing laps when his engine expired, handing the position to teammate Mike Smith, who had replaced Russell.

At Sears Point, Picotte arrived still suffering from a horrific, high-speed snowmobile accident in Quebec a month earlier, but he managed an 11th place finish on the technical circuit. He finished 7th in round one at the Road Atlanta double-header but DNF’d the second. Smith was running 8th on Sunday when a scary crash put him off and burned the VR1000 to a crisp. If it wasn’t for bad luck…

More than 90,000 spectators turned out for a weekend of World Superbike and AMA Superbike races at Laguna Seca, but Team Harley was unable to rise to the occasion, with Picotte and Smith finishing 9th and 10th, respectively.

The 2001 season finale, and the swan song for the VR1000, came at Virginia International Raceway. Nagged by persistent clutch and transmission problems, Picotte struggled to finish 12th.

Willie G. Davidson was on hand for the last rites and to tout the street version of the VR engine in the dragster-style V-Rod. The 60-degree Porsche-developed mill made 115 horsepower, the bike weighed 650 pounds, and it was often described as the answer to a question no one had asked. The V-Rod was an inauspicious end for the VR’s legacy.

“The VRs had a few moments of looking good, due to having great riders,” reflects Erik Buell, “but overall it was a failure.”

Before the program was officially canceled, Buell was given a chance to quickly improve the bike.

“The guys modified one VR by splitting the radiators, moving the motor forward, and changing the swingarm geometry,” Buell reports. “Still short on airbox volume, the bike was taken for testing and was more than a second a lap quicker than the standard model. After that, we got out the original chassis and cobbled a VR motor into it. However, the program was shut down and that bike never got tested.”

As it has been throughout history, Harley’s annual racing budget was in flux. The long-term prospect for racing success, and its commensurate price, never kept pace with shifts in management personnel. And marketing mavens convinced management that MoCo customers weren’t much interested in roadracing.

The VR1000, which entered the fray overweight and underpowered, more or less stayed that way through eight racing seasons. At what one insider estimated was a cost of $50 million, the project was a dismal failure.

However, H-D is pinning its hopes for the future on another liquid-cooled, 60-degree V-Twin, the Revolution Max used in the Pan America 1250 and Sportster S, and more models to come. So perhaps some of the VR’s development is still paying off.

Hardly a Porsche-developed engine. They helped make a Harley-developed racing engine streetable. However, it was still not a satisfying engine for a road bike, and it was definitely lacking in the torquey feel that make Harleys so satisfying to ride.