Most of motorcycling’s pioneers started with bicycles: Glenn Curtiss, Indian’s George Hendee and Carl Hedstrom, and Walter Davidson, to name a few. Many of the first pro racers also made the transition from pedal power to engine power in the early 1900s, with one notable exception.

The need for speed hit young Albert William Burns early on. Born in 1898 in Oakdale, California, Burns’ family moved to Oakland when he was a youngster. This period, 1908-1912, saw a national surge in the popularity of motorcycle racing, and Burns was pleased to find a Pope dealership not far from his home.

By age 12, Burns was almost a fixture in front of the shop, inspecting the various machines and questioning owners of bikes coming in for repair. Eventually the manager gave up trying to shoo him away, and at 13, Albert was hired to help clean up the shop.

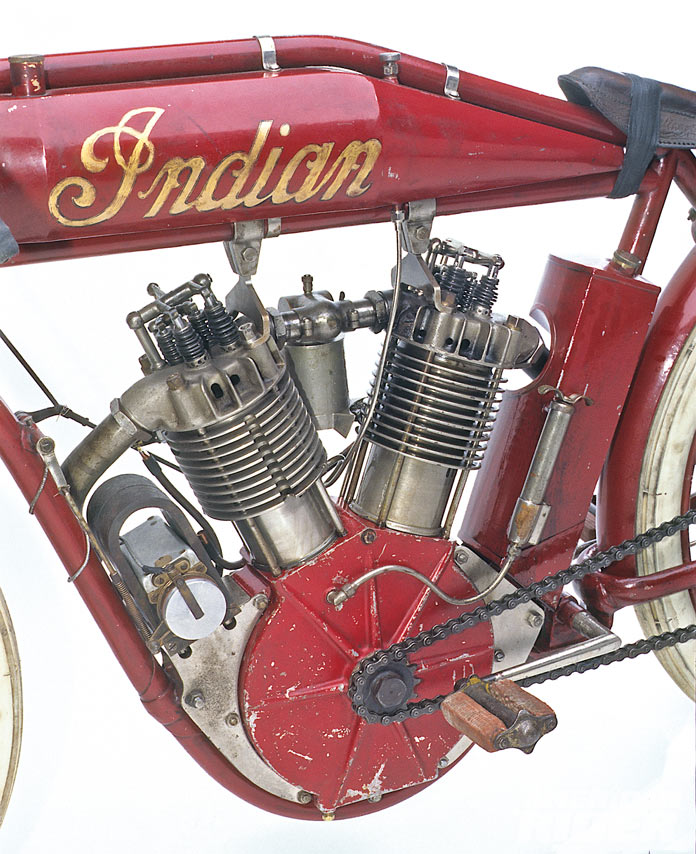

The following year Burns managed to build an Indian V-Twin racer, likely from donor parts and spares in the shop, and entered his first race in Sacramento. When the 14-year-old finished fourth against a field of experienced riders, the protests soon followed. He was too young, they complained, and too small. The promoters banned him from the next race, where he reportedly sat on the fence and made faces at the pro riders.

In 1915, still aboard his home-built Indian, Burns won three events in Pleasanton, California. It was here that Albert was dubbed “the Shrimp” by the older riders, according to Daniel Statnekov’s Pioneers of American Motorcycle Racing. Undeterred, the enthusiastic youngster took it in stride, and the nickname stuck. The impish grin was still there, seeming to say, “Call me what you want, just don’t call me late to the starting line.”

By this time, the Indian OHV 8-valve racer had been available for three years, but its $350 price was beyond the reach of most privateers. The Harley 8-valve was about to appear, but at $1,500, it wasn’t meant for independent racers. And the speedy overhead-cam Cyclone V-Twin was serving notice that it was now a three-way contest for top honors. The game was about to get even more serious – and dangerous.

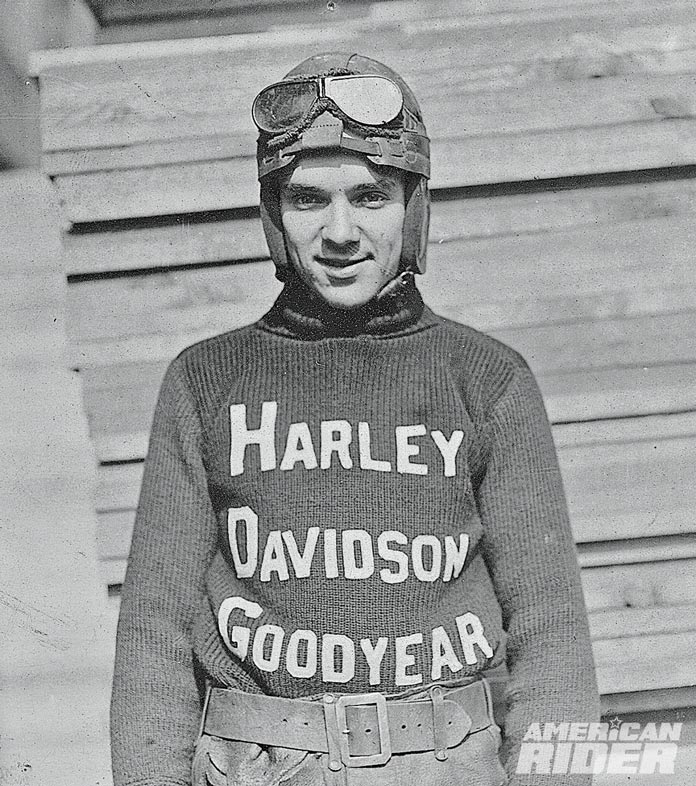

The advent of World War I limited the competition schedule for two years, but by 1919, the factory teams were back in full force. Shrimp Burns became a member of the mighty Harley-Davidson Wrecking Crew. The Milwaukee team dominated the June 200-mile National in Los Angeles, where Burns was fourth behind Ralph Hepburn, Red Parkhurst, and Ray Weishaar. On the boardtrack in Sheepshead Bay, New York, Burns narrowly won the 100-miler ahead of teammate Maldwyn Jones.

But Burns’ career as a factory Harley rider would last only a year. Some accounts attribute it to a personal issue between him and team captain Otto Walker. Others say that Shrimp was resistant to manager Bill Ottaway’s rigorous training program, while some purport he left because of a dispute over who would and wouldn’t ride Harley’s 8-valve in certain events. In any case, Burns switched to the Indian factory team in 1920, but the change had little effect on his popularity among the fans. He was still the smiling, irrepressible kid who could beat the big guys at their own game.

Burns led the first seven laps of the 100-mile Ascot season opener on the Indian 8-valve until loose handlebars forced him to pit and put him out of contention. A week later, in the 25-mile National, Burns won convincingly, breaking the old record by almost a minute and a half. The fans went bonkers, lifting Burns up and carrying him past the grandstand. He went on to win the 5- and 10-mile Nationals in Denver.

In April of 1920, a new, 1.25-mile, $500,000 boardtrack in Beverly Hills hosted motorcycles for the first time. Riding an Indian Powerplus, Burns qualified in the 10-lap event by just nipping Otto Walker’s Harley 8-valve at the line. In the 25-miler, Burns’ engine seized and he crashed hard, tumbling down the track and collecting bruises and splinters.

Burns had to sit out the 50-mile event while getting bandaged up, but he returned for the 15-mile consolation race on a borrowed Indian. Sitting third on the final lap, he again took the high line to slingshot past the Harleys of Ray Weishaar and Ralph Hepburn. His average speed was 102.6 mph, a new side-valve record. (A film clip of the race is available on YouTube.)

In August, due to be married in a few weeks, Burns was dicing again with Ray Weishaar at a Toledo, Ohio, flat track when a savage crash occurred. Accounts of the accident vary, but it seems Burns got into a turn too hot, saved it before hitting the fence, and came down into the path of Weishaar’s bike. Both riders went down, and Burns went head-on into the fence. He was rushed to the hospital but succumbed to his injuries two days after his 23rd birthday.

Burns was arguably the most popular rider of the time. Tenacious on the track but rarely seen without a grin, he was both a gifted rider and a cheerful, fun-loving youngster who was always willing to help other riders at the track.

“He would try things I wouldn’t do, but he was a terrific rider,” said Harley teammate Jim Davis. “And he was a real nice fella. He was the only one who came to see me when I was laid up in the hospital in Michigan.”

Albert “Shrimp” Burns was one of the most colorful characters during motorcycle racing’s golden age.

Related: Obscurity Files: The First Fours

Related: Obscurity Files: The Harley-Davidson Topper

Great photos, amazing chapter in American history. With motorcycles and cars in their pioneer days, competing in the new world of motorized transportation, a time of practical travel over horse n’ buggy and the euphoric thrill of riding briskly through the countryside and feeling the open air.

It’s fascinating to hear stories from this early era of motorcycling, and we’re glad you enjoyed it!