I’d always admired the Harley-Davidson Road King, but from the 2007 to 2016 model years, the primary had been widened to accommodate the six-speed transmission introduced with the 2007 model. For the 2017 model year, Harley once again redesigned the primary, resulting in a slimmed-down cover. Finally, I could plant both feet on the ground while seated! The new Milwaukee-Eight engine sealed the deal, and in July 2016 I rode my new Tourer out of the showroom.

Although Harley claims a seven-percent reduced lever effort to disengage the new Assist and Slip clutch, I soon discovered that the amount of pull needed to not only pull in the clutch but keep it in was much greater than other Harleys past the mid-2000s when the clutch was redesigned. In fact it was similar to the effort required on both my 2000 Harleys in which I’d installed a clutch assist product that considerably reduced the amount of pull needed. No clutch-assist product can function with the Assist and Slip clutch, nor can any adjustments be made to the clutch itself.

Hearing about my plight, John Magee of Bandit Machine Works in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, reached out to me with a solution. John has been making clutches for over 30 years, dealing mostly with racers that place extreme demands on their bikes’ components, often exceeding the original equipment’s capabilities. The company soon expanded to serve the street rider that has different but equally demanding needs. Listening to me describe the problem I was having, and, after learning about my riding style, he recommended the Bandit Machine Works Sportsman Superclutch for Big Twins.

Eager to have the new Bandit clutch installed, I rode the 150 miles from my home to Lancaster where John and his lead tech/machinist Jeff awaited my arrival. Components included in the Sportsman Superclutch product are the clutch hub, pressure plate and all the hardware for the plate (spring cups, release bearings, etc.), 11 friction plates, 10 steel plates, steel backing plate, six standard springs, six heavy-duty springs, 30 spring shims, assembly lube, and a mainshaft nut to replace the stock nut.

My bike went up on the lift, the primary cover was removed, and then the clutch hub taken out, as per the factory service manual instructions. Bandit’s detailed installation instructions call for thoroughly cleaning the clutch shell, as well. During this process, I was given a tour of the extensive and thoroughly impressive machine shop where Bandit products are made and the shop where they’re tested.

Jeff prepped for the install by disassembling the new clutch except for the snap ring keeping the clutch bearing in the hub. He applied a light coating of oil to the to the clutch center hub and pressed the hub into the bearing of the clutch shell. It’s recommended that a new bearing be installed, but my bike was still so new, that step wasn’t necessary. Next the new snap ring was installed onto the hub and the transmission splines lubricated with the supplied moly disulfide assembly lube and then the threads on the shaft end were cleaned.

The clutch shell, chain and engine sprocket were installed, Loctite applied to the mainshaft threads, and the new mainshaft nut installed and torqued to spec. Before installing the clutch pack, the friction plates were wetted on both sides with the oil that’s to be used in the primary. Often people will soak the plates, but that’s not necessary; a layer of primary oil will suffice in a closed primary system. Actually, the plates don’t even need to be wet, but according to John, the coefficient of friction will change between dry state and wet state, operating differently as they absorb oil. If they’re installed dry, they will pick up oil in operation from the oil circulating in the primary, so John prefers to wet them to start with so they don’t change in operation. Note that the steel plates will get wet from the friction plates.

Detailed instructions are given for installing the clutch plates in the correct order, as well as measuring the stack height of the clutch pack. The Assist and Slip clutch has nine friction plates and eight steel plates, while the Sportsman Superclutch has 11 friction plates and 10 steel plates. Bandit has squeezed more, slightly thinner plates into the same area and the clutch winds up a little fatter because of it. More plates give the clutch more surface area, and each of the Bandit plates has a larger surface area as well, in fact, 238 percent of stock. This allows the spring load on the clutch pack to be reduced so that the lever effort is less, exactly the effect I was hoping for.

John compared the weight of the stock springs against the gold springs that come with the Bandit clutch. The three springs out of the stock clutch totaled 295.5 pounds of static spring pressure, while the six springs from the new clutch totaled 210 pounds, meaning that the Sportsman Superclutch would require only about 65–70 percent spring load (about 30 percent lighter). We could also have installed shims to adjust the amount of pull required, but that wasn’t necessary for my bike.

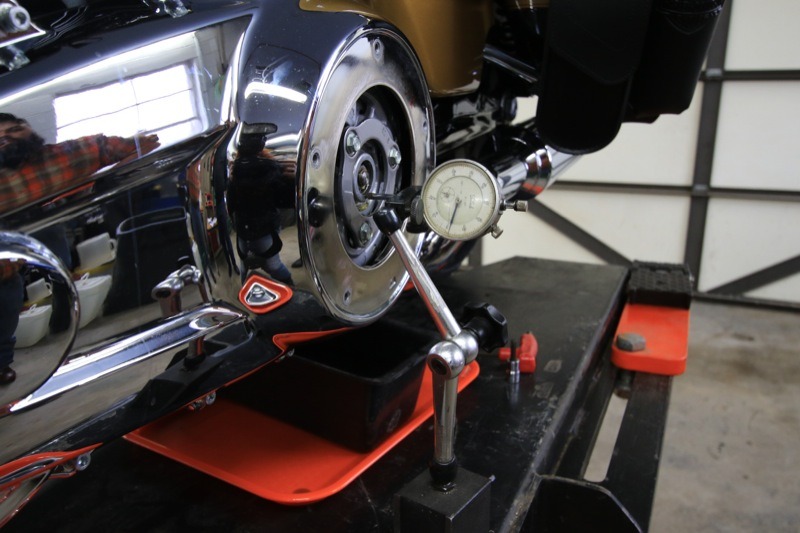

Installation of the clutch plates was followed by installing the pressure plate and springs, adjusting the clutch release free play and reading and adjusting the runout on the pressure plate, as per the included instructions. Four color-coded springs are available for this clutch; packaged with the product are the two most-used spring sets, gold, which is standard, and silver which is heavy duty.

When the stock Assist and Slip clutch was visually compared to the Sportsman Superclutch, the most obvious difference was the spring setup. John relayed to me some of the history of springs in Harley clutches, starting with the 10 coil springs in the Panhead/Shovelhead clutch. When Harley went to the Evo and a wet clutch, they used diaphragm springs which felt lighter to pull when the clutch was completely disengaged (all the way in at the grip). With the Assist and Slip clutch, three heavy springs are used because a diaphragm won’t work with a moving pressure plate which turns in relation to the clutch hub, plus there is a ramp between each spring, leaving no space for additional springs. Each of these three springs slides into slotted pockets; the steel spring slides against the aluminum pressure plate in the pocket which enables the assist-and-slip function. The Sportsman Superclutch uses six light coil springs instead, as there are no pockets or ramps to contend with.

Since the primary cover is slimmer than prior-year models, a small area of the extra cast material on the inside of the primary cover needed to be cleared to create enough space for the pressure plate. Otherwise, the install is completely bolt-in. After the primary cover was clearanced, it was re-installed and primary fluid added. The instructions include Bandit’s recommendation for the amount of fluid to be used as well as specific brands that work best with their products.

Time to test ride! The difference in clutch lever pull was immediately noticeable, as was the elimination of the “grab” at low speed when I first let the clutch out. And because the new clutch’s pressure plate travel is increased, meaning that the clutch plates separate more, there’s no “clunk” between gears. What I also noticed was the loss of the assist-and-slip effect, however, this isn’t a function that I miss. I just need to avoid letting out the clutch too quickly on downshifts to avoid lurching, just as I learned to do when I started riding.

Once the bike was back in the shop, John compared clutch lever effort between the Harley and Bandit clutches. He’d constructed a tool just for this purpose, and already had measured the amount of effort required before the stock hub was removed. It took 14 pounds of pressure to disengage the clutch and 12 pounds to hold the lever in once disengaged. With the new clutch and lighter springs, it took only eight pounds to pull in the clutch and six pounds to keep it pulled against the grip. And with the heavier spring, which we experimented with, pull required was nine pounds to disengage and seven pounds to keep disengaged. This correlates with the static spring pressure measurements mentioned above: 30-percent less pull. And the installation instructions detail how to adjust the spring pressure if I want to experiment further.

Before I rode home, John mentioned that with many applications, his customers see a 50-percent reduction in lever pull. He explained that the reason I experience only a 30-percent lighter pull is because of Harley’s redesigned transmission for 2017 touring bikes. The hydraulic mechanical advantage between the master cylinder and the slave cylinder in the transmission was decreased to get increased throwout on the pressure plate so that it doesn’t clunk going into gear. This also adds to the heavier lever effort required. That said, I’m more than happy with the lesser amount of effort required for pulling in and holding the clutch. And my hands are a lot happier, too.

Bandit Machine Works

#039835 (for hydraulic operation), $545

banditmachineworks.com

717.464.2800

I’ve only been a Bandit customer for a couple years now and have their systems on both my Harley drag bikes but I’ve found their customer service to be Topnotch, whenever I call Bandit for advice or instructions both John and Jeff will take the time on the phone to thoroughly explain every detail of my request until I understand, I’m so glad I’ve discovered this company and their products.

I love them. I have a mildly built 88ci. to a 95 I noticed as soon as I pulled out from The Shop(Salem Va) that went i shifted into 3rd gear it hooked up great. I’ve had them in my bike 5 years. One of my best purchases.