Touching the Circle

In Part I, Brooklyn set out for the Arctic Circle with eight other riders in an effort to cope with his pent-up anger. Along the way, he discovered not only beautiful country and breathtaking views, but several rules of the road as well. He called them his Long-Distance Maxims: LDM #1) You will lose your shit; LDM #2) You will drop your bike; and LDM #3) Your technology will fail. Here, in Part II, Brooklyn continues his journey into the Great White North with his four remaining riding partners and adds to his list of discoveries.

The Alaska Highway actually starts in Canada and was originally built to connect a series of military airfields during World War II, right after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The road was constructed under the harshest of conditions—current winters are mild by comparison— and by a mostly black construction crew. (The military was segregated at the time and black soldiers were not sent to active duty, but their incredible performance in getting this road built led to integration of the military during Korea.) The highway is still the only land route to Alaska. It begins in Dawson Creek, British Columbia, and winds 1,522 miles to Fairbanks, Alaska.

And it is some of the most challenging mileage I’ll ever ride. Most of it is quite good, actually, well-paved and taken care of, particularly in American territory, but winter does a lot of damage to the road and so there are difficult and treacherous stretches. Some of the road was so rife with frost heaves that our bikes would get airborne—repeatedly. This kind of road will begin without warning or with the advent of only a tiny little orange flag, and hitting it at 60 mph will make your sphincter pucker. Hitting it at that speed in a curve, where you can feel your front end twisting and the entire bike skipping toward the trees, will make you believe in a higher power! And doing it while passing one of the thousands of RV’s… well, that’s just insanity.

In many places, the road is completely torn up. Pilot cars lead long lines of motorcycles, bicyclists, campers, and trucks through mile after mile of construction zones. The riding can be particularly challenging here since the water trucks that keep the dust down also keep the dirt rather wet. And if it isn’t mud, it’s large, loose gravel. The easiest way to traverse dirt and gravel is at about 45 mph. The bike just floats over most of the bumps and ruts. The front will wander a bit, so just trust those two large gyroscopes called “wheels.”

There are some great places to stop and a lot of beautiful scenery, such as Lakes Kluane and Louise. Many of the businesses and destinations are closed in the off-season, and it’s important to note that everybody closes by 8 or 9 o’clock at the latest. If you haven’t eaten and found a room or campsite by then, you’re not likely to.

The days were cool, but throwing on some extra layers for warmth was enough. We never reached for our electric gear because it just isn’t that cold in Alaska in the summer. As for rain, the showers would last about five miles and were light—then we’d have an hour of clear riding with sun, then another rain shower. This pattern held for days on end. The scenery makes it all worth it, even in the rain. Long-Distance Maxim #4: Keep your raingear on.

Breaking down, breaking up

The night before reaching Fairbanks, we stayed in tiny Tok, Alaska. This is a major crossroads area, where the highway up from Anchorage meets the Alaska Highway. There, we camped at Thompson’s Eagles’ Claw biker’s roost, a campsite specifically for motorcyclists. The Thompsons have put a lot of work into building this spot for bikers and are continually expanding it. While there, we didn’t have to pitch tents. We stayed in half-wall tents, similar to the kind prospectors would have stayed in. When we were there, we met another Sportster rider, and we all sat round the campfire and had a good night together.

After a night in Fairbanks, we headed north in a grey, drizzly atmosphere and very quickly climbed up into fog banks. The fog was eerie and the intermittent drizzle even worse. An hour out, I was tightly snug in my riding gear and just beginning to think we were all going to make our goal when the rider two spots ahead of me, Erica, began slowing down abruptly and pulled off onto the very skinny shoulder. Lee, who was immediately ahead of me but behind her, rode on, perhaps intending to catch the others and pull them over as well, so I pulled over with Erica. All through this trip Erica had been gung-ho and enthusiastic—her yellow bike and helmet and black riding gear made me nickname her Queen Bee—but now she looked a little buzz-killed.

“I think I broke a throttle cable,” she said, after we’d pulled our helmets off. We were 60 miles north of Fairbanks on a road frequented only by the trucks hauling supplies north. We were out of cell phone range. We may have been out of satellite phone range, too. I’d noticed that at this latitude, all the solar panels and satellite dishes were pointed straight out at the horizon.

While waiting for the others to come back, we both got our tools out and took apart her throttle housing. And sure enough, the throttle cable had broken at the swaged fitting— a not uncommon problem with these cables and a good reason to check them at major service intervals. Now, I had zip-tied spare clutch and idle cables to my regular ones before I left home, having gotten that tip from other long-distance riders. I’d chosen an idle cable on the theory that it could be pressed into service as a throttle cable, too, but the reverse was not possible. So now I had a chance to test my theory— on Erica’s bike!

Over the next half hour, I wound her idle cable around the other way and fitted it in place of the throttle cable. This involved taking off her air cleaner, which neither of us had the proper tools for, but we made do. Just after I finished buttoning it all back up, Lee showed up. The others were waiting up ahead, he said. Erica was angry that everyone hadn’t turned around immediately, but held her temper well. Maxim #5: Something critical will fail; have spares.

Erica now had a choice to make: 400 miles on dirt on a jury-rigged throttle cable and trusting the carb throttle spring would do its job, or 60 miles on paved road back to Fairbanks, at which point reaching the circle wouldn’t be an option. Wisely, she chose to head back. One of our road rules was that nobody rides alone out here, and Ron immediately volunteered to go back with her. That put us down to three riders to go to the circle until Bootie showed up and announced that the beginning of the famous Dalton Highway was about 20 miles farther on. This meant he’d now burned enough gas that he wouldn’t make the next gas station in either direction. He had no choice but to stick with Ron, who had plenty of gas for both of them in his six- gallon tank!

That left Lee and me. Should we stick with the group, or make a try for the circle? It was a hard decision that took about a tenth of a second to make: We’re going to the circle! We haven’t ridden all this way to not even try. We said our good-byes and wished Erica good luck getting back. We’d stick to the itinerary and be back in Fairbanks the next night. Bootie gave us the satellite phone, believing we might need it more than they.

Two for the Circle

At this point, the trip became like something straight out of a road-trip buddy movie. Now, I haven’t written much about Lee yet. He was mostly quiet and kept his own counsel, but was the kind of rider you come to respect. He rode his Road Glide like he actually lived in the saddle, chain-smoking at 70 mph. He kept his bike clean and took meticulous notes about costs, but otherwise was completely laid back. He’s the kind of rider who doesn’t own a full-face helmet and doesn’t put on rain gear until his cigarettes are in danger of getting too wet to light. In other words, he’s one of the best riding buddies a guy could have.

We put on all our rain gear and kept it on, even when the sun came out, because once we started the Dalton Highway, the dirt, the grit, and the grime was overwhelming. We had a single planned gas stop because that’s all that was available between us and the Circle, and once we passed a certain sign saying 80 miles to the Yukon River crossing, Lee pointed out this was the point of no return. We had enough gas to get back to Fairbanks on fumes. Beyond this, we were committed. It didn’t bother us in the least.

The Dalton Highway is another purely utilitarian road. It was built to get the Alaskan pipeline built and is maintained solely to keep the crews and supplies going back and forth to maintain the pipeline. Tourists are welcome and add variety, but on this road, the haul trucks are king. You’d better be a good rider because this surface goes from being “pleasant country back road dirt” to “hellish muddy rutted potholed washboard gauntlet” in a tenth of a mile. I discovered I could partially stand on my passenger pegs and thereby transfer most of my weight directly to the swingarm, hopefully taking some of the load off my shocks.

It was sunny and warm when we reached the Yukon River crossing, which is a beautiful, long bridge over an equally beautiful river. The bridge is surfaced with worn wooden planks laid along the bridge, not across it. We found the only gas pump in town, and then went inside to pay and see if we could get some lunch. The building there is made of prefab construction units spliced together and was used as a bear’s den a few years ago. It was charming, and the food was excellent.

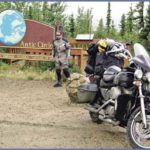

Bellies full, we got back on the dirt for the final leg of our trip. A couple hours and a few fierce rain showers later, we finally arrived at the Arctic Circle, latitude 66° 33′ N. Our bikes were grey from one end to the other (due to the calcium chloride from the Dalton Highway) and we weren’t looking much better, but there we were. We took the requisite photos and started to set up camp.

There’s a primitive campground at the circle and we took advantage of it. It was very warm—about 80 degrees—and fairly humid, too, so the famous Alaskan mosquitoes were out in force. We doused ourselves in bug juice and put on head nets and got camp set up. Lee and I were dismayed to find ourselves without water. I thought I’d brought a liter bottle with me, but apparently not. Fortunately, Lee is a car salesman—he talked some visitors into giving us a couple bottles of water (they were headed onward and had plenty in their camper). That’s the kind of people who are up there; you help each other, because God knows what goes around, comes around.

Camping that night was interesting, especially since I was awakened at 1:00 a.m. by the sun shining between some trees, through my tent window, and into my eyes. Up here, pitching a tent east-west as I usually do doesn’t accomplish much since the sun just travels in circles for a month or so.

For want of a belt

As it developed, the journey home proved even more of an adventure than the ride up. Lee and I hit the road early and ate breakfast at the Yukon River Camp again, fueled up, and zipped back to Fairbanks, where we ended up staying at a bed-and-breakfast (I use the term loosely) that was… well, the next time you’re up in Fairbanks, just look up the AAAAOne Bed & Breakfast Inn. Then find another place to stay.

While we were gone, the others had decided to go to Anchorage a day early, which left Lee and I still on our own. We decided to take the direct route home because we’d done what we’d come to do. We left Fairbanks the next morning and by afternoon we were in Tok, a day ahead of the rest of the group, who would have to come up from Anchorage to Tok to get back to the Alaska Highway. We skipped staying in Tok, preferring to keep going and cross into Canada first. We did drop off the satellite phone in Eagle’s Claw, though, since we knew Bootie would be passing that way. We passed through Alaskan customs and entered no-man’s land—a 20-mile section between the Alaskan and Canadian checkpoints.

About eight miles short of the Canadian point of entry, I hit a snag. Literally. At Snag Creek, I lost power to the rear wheel. I quickly determined the engine was still running fine, but no amount of throttle would send power to the wheel. A sinking feeling passed over me. I didn’t need to look to know that I’d broken the drive belt.

Lee and I pulled over and found the belt. It was in good shape except for where a large stone had apparently lodged directly in the middle of the belt and caused a break. For a while we tried to thread the belt back through the front sprocket, in an attempt to reinstall it and zip-tie the loose ends together and ride the last eight miles, but that was futile. And we’d left the satellite phone back in Tok!

Eventually, Lee rode off to find a phone, and I ate dinner out of my saddlebags—canned peaches, beef jerky, water, and marshmallows. (Maxim #6: Always carry extra food and water.) I found that I was not angry. This, after all, is what ad- venture is all about and I was really having some! And maybe Alaska and the Arctic Circle had tamed that anger somewhat—or at least let me put it into a box until I got back home. After about three hours, Lee came back. He’d borrowed a phone and made a lot of calls, and got a towing company to drive a truck 250 miles from Whitehorse to pick my bike up the next day.

Lee said Beaver Creek was right across the border, so I flagged down a helpful motorist and hitched a ride, taking all the stuff off my bike. Lee and I spent the night in Beaver Creek and he got going early the next morning. I would have to wait until the afternoon for the tow and I didn’t see a need to slow Lee down any—he had things to do back at home. I thanked him for having my back and wished him well.

Early that afternoon, I heard a familiar engine and noticed a very familiar profile pass by. It was Dan. I assured him I was fine and I was glad to see he was really enjoying himself at last, too. This was, in fact, a great day. The sun was out, the temperature mild, and as far as I could tell, everyone was fine. After all, a broken belt isn’t a broken leg.

The tow truck came at about 4:00 and we headed west, picked up my bike, then headed southeast again. We had 250 miles of rough terrain to cross, with my bike strapped to a slick flatbed. All went well until we ran into the first of two construction zones at Lake Kluane. We had to wait 90 minutes for massive earth movers to actually create a road for us, as the one that had been there two hours ago was gone. When we finally got through that stretch, we found my bike had fallen over on the flatbed. I wasn’t that surprised and my bags and crash bars protected the bike well. As we were dealing with that, the driver noticed fluid leaking from the rear differential and he was having trouble with the parking brake. He tried to fix it, even borrowing some oil off another tow truck, but even before we reached the second construction zone, less than two miles distant, we were smelling fire.

And that was it: 150 miles from Whitehorse and my rescue now needed a rescue! The driver got a ride to the other end of the construction, where he borrowed a satellite phone and called his boss, who immediately set out with a tow truck for the tow truck. In the meantime, I began polling drivers who were coming through the construction zones to see if anyone was going to Whitehorse and asked if I could bum a ride. I quickly found a sympathetic couple and, grabbing only the essentials, climbed into these good Samaritans’ little camper-van. They dropped me off in Whitehorse at 3:00 a.m.

Though the dealership did their best to speed me on my way, the replacement belt had to be ordered and shipped up, so I spent a total of three and a half days in Whitehorse. At least this time I got to sample some of the food and local sights I’d missed the first time through, including their dry-docked passenger steamship, the SS Klondike, and some of the several dozen murals painted on buildings throughout the town. It’s not a bad place to spend some downtime, for sure.

Seeking meaning

While waiting around, I read an article on wilderness survival schools in Experience magazine, wherein author Jack Armstrong noted that there’s a surge of interest in the simple skills. Let’s get back to basics is not just a phrase, it’s the current fad. It seems everybody is beginning to feel a little too dependent on the prepackaged, the uniform, the electronic and “this sense of dependency and vulnerability doesn’t sit entirely well with us.” True, that. What he implies is that people are angry with themselves and a little scared. Can we survive when the batteries give out and the machines stop? Could any of us live even two weeks without our delivery systems as we know them?To be sure, I depend on small groceries and restaurants on motorcycle trips, but there is camping. It’s a beginning of real independence. I do have a comfortable shelter I can erect nearly anywhere. I can start my own fires and cook my own food. And that really helps the whole rest of the year.

So, was this trip simply an act of survival, for the others as well as for me?

I made 500 miles the day I left Whitehorse and pulled into the provincial campground at Liard Hotsprings, B.C., just before they closed the gates. The hot springs, by the way, are worth taking a dip in on the way up and on the way back. I soaked for an hour in the evening and then got up at 5:00 a.m., went to a more distant pool and went skinny-dipping for a half-hour. But don’t tell anybody.

And there ended the great Alaskan adventure of 2007 for me. From that point on, it was 600-mile days—longer, darker nights, but brutally hot riding during the day—through uninteresting, flat Canadian countryside.

The others all made it back home safe and sound, and 11,500 miles later, I eventually got back to Brooklyn myself; a happier, less angry human being. And I see now that it wasn’t anger that drove me to Alaska, but despair; worry that what I see around me is all there is to life. I needed to reassure myself that I had still had the skills I’d learned as a Boy Scout: to make fire, shelter, to cook food, to do things in a simple way; that I could still travel on a bike and enjoy the uncivilized country, and that I can still turn aside the anger of living a “civilized” life.

An awesome story! Been planning my trip for 3 years, Was set to go last year but work and lay off at wrong time impacted that plan, this year looking like a real possibility, already got 63,000 on my 2011 Dyna and it is the bike I want to take, man and machine thing, I have spoke wheels which look great but having a flat in North Texas I couldn’t do anything but call the nearest Harley shop to come get me, That is a concern out in the middle of nowhere, I miss my tubeless like on my fxst/c, plug, inflate. one up on this trip, it too is a bucket list thing as I am getting if not there already….old. K. Doerr