Muscling the miles

Good looks can take you a long way

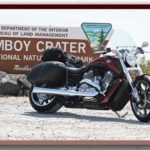

Regardless of what style of motorcycle you ride, and what your reasons were for choosing that style, it’s inevitable that sooner or later the urge to do some serious road work will come upon you, and unless you’ve prepared for that eventuality by buying a bagger, you’ll be obliged to address the challenge of packing some gear on the bike. A bunch of it. Even the most single-purposed high-powered barhopper will be expected at some point to haul freight—or at least the groceries. Some models of machine are more amenable to that indignity than others, and among those others are the breed of mount dubbed the “power cruiser.” And among the power cruisers least inclined towards that kind of treatment is the VRSCF V-Rod Muscle.

The Muscle’s resistant to the idea, and why shouldn’t it be? It’s as close as Milwaukee’s ever come to producing a pure cutting-edge, unapologetic fashion statement, and if a quick squint at the bike’s extreme muscle car-inspired styling is insufficient to convince you of the fact, you need look no further than the advertising campaign that launched the beast, featuring it-girl supermodel Marisa Miller draped languorously over the machine. With an introduction like that, the Muscle can be forgiven for copping an almighty attitude.

Pressing the Muscle into touring duty is sort of like putting a yoke on a thoroughbred, or maybe press-ganging a show horse into the Pony Express, but that’s exactly the kind of practical-minded sacrilege we here at Thunder Press feel perversely compelled to do in the interest of fleshing out the entire range of possibilities for any configuration of machine. It’s a perversion of ours that extends even so far as to call upon the debonair Muscle to pull off a six-day, 1,500-mile excursion to the Laughlin River Run.

As unlikely a proposition as it may seem to pack up the model for the undertaking, it can definitely be done, and that’s due entirely the fact that in anticipation of just such an eventuality, The Motor Company engineered—and I do mean engineered—a set of hard bags for the bike (91172-09 Rigid Saddlebags, $749.95).

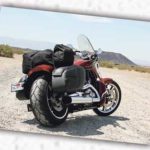

These bags are not quick-release. They’re not even slow-release. They’re no-release, meaning that in installing them you’re committing to the creation of a distinct model of V-Rod altogether. Call it the VRSCFLH, perhaps, or for you anatomy buffs, the Mio Glide. Regardless, making that transformation is the only feasible means of bagging up the boldly unique and super-sanitary rear end of the Muscle. Realizing that, the Harley designers went to admirable lengths to fashion a setup that not only brings some meaningful carrying capacity to the bike, but also complements its design beautifully. We’ll get to the functional details of what they’ve created forthwith, but first we need to install the things.

To make that happen, we turned to master-wrench Rich Roy at Cycle Works in Santa Rosa, California. We hadn’t intended to. We had intended to do the deal ourselves, ripping into the shipping carton, extracting the DIY installation instructions—which, in our experience with most other Harley accessories, are usually thorough and amateur-friendly—and having at it.

We started in and were actually doing pretty well until we actually read the first step of the procedure which said to remove the main fuse by following the directions in the V-Rod Muscle service manual. Like we have one of those. Step 2 called for us to consult the same text to guide us through the removal of the seat and pillion, and reading on from there we came to understand that this procedure would further entail dismantling a goodly portion of the Muscle’s hind quarters, including relocating the side-mount license plate frame and installing a gas shock strut under the seat. At that juncture we decided that the simpler approach to all of this was to punch seven digits into the keypad of the phone and get Rich involved.

We dropped the bike and boxes into his lap and a few hours later the makeover was complete, including the affixing of a Quick Release Detachable Mid-Sport Windshield (57610-09, $334.95), and we got the bike back along with some words of advice from Rich: “Don’t try this at home.” He said some other colorful stuff, too.

The load-in

The saddlebags are a pleasant surprise. Despite their form-fitting attachment and appearance, they actually have a respectable capacity, including mesh pockets on the inside for storing the road essentials you need to get your hands on without a lot of digging. The double-zippered lids peel back to expose the entire interior, making packing and unpacking convenient, and the lids have magnets embedded in the ends to snap them shut even when unzippered. That feature offers some peace of mind for the absent-minded among us (guilty) who occasionally space out zipping things shut.

While the saddlebags hold a fair amount of stuff—certainly enough for solo overnights or dashes to the convenience store at the end of the day for provisions—they’re not sufficient for a six day trip, and thus we need to fasten a duffel bag on the bike with a pair of bungee cords. That presents its own challenges, since finding suitable bungee hook-up points takes some searching. The default bungee points on virtually all Harley models are passenger footpegs and the rear turn signal stalks; the Muscle has the former but not the latter, owing to the uber-cool rear light array embedded in the fender tip that incorporates the indicators. So that’s out. Also out is another common bungee hook site on bagged bikes, the framework of the saddlebag mounting brackets. The infrastructure of these bags is so tightly integrated into the bodies that no such opportunity exists. After much inspection and doubt, we end up hooking the cords to the lower shock absorber mounts, and that works out well. The cords stretch straight up to the pillion area and forward to the footpegs providing a pretty ideal placement, and one that functions flawlessly for the duration of the journey. The cords also don’t obstruct the hinging open of the seat when accessing the gas tank. The same can’t be said for the left saddlebag, however, which explains that gas shock strut included in the saddlebag installation kit. Since the front of the left saddlebag impinges ever so slightly on the seat in its open position, the seat won’t stay open while fueling the bike without a touch of gas-charged assist. The strut works brilliantly. I told you this setup was engineered.

And down the road we go

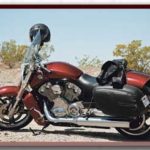

The riding posture aboard the Muscle is, by design, aggressive. The bike’s seat is positioned more rearward than other VRSC models, and the handlebar doesn’t reach back much from the steering head. The ergos, in other words, are better suited to the stoplight drags than the horizon dash. Kicking back in the saddle, or even, for shorter riders, sitting bolt upright are not options except as “Look Ma, no hands” moments. Still, as is the case with virtually any configuration of mount, with time and miles, experimentation and subtle assimilations, comfortable comportment comes.

And though we weren’t optimistic about that happening on this particular machine, it did, though it took longer than usual. Where at first 150 miles seemed like an ordeal, a couple of 300-mile days came without undue fatigue or discomfort and then a 400-miler was a stroll in the park. Surprisingly, it’s the Muscle’s Spartan-appearing seat that most enables that outcome. It’s a wide perch, and it’s not deeply notched like the conventional V-Rod seat. It facilitates skootching your glutes around and relieving pressure points over the long haul.

Also worth pointing out here is that when we first met the Muscle at its launch last summer, the location of the exhaust headers in relation to the forward-mounted operator footpegs was cause for concern. It appeared that sooner or later your boots would end up sitting on or pushed up against then. It also appeared that heat could become a comfort issue down there. That proved not to be the case at all. There was no noticeable heat issue even in 90-degree riding, and after 1,500 miles, no heel marks on the pipes.

Touring in hyperspace

The rewards of having morphed the Muscle into a mule come with the flick of the throttle on the open road. The 1250cc Revolution motor is hella potent, producing something on the order of 121 horsepower and 86 pound of torque. It’s a high-revving brute and the real video game starts up at about 5,500 rpm, but there’s neck-snapping thrust on tap at virtually any speed. It’s a weapon on the highway, capable on a whim of exploding past vehicles blocking your passage, pulling off passes on two-lane roads in crazy-short distances. It’s habit forming, and the Muscle will bring out the mischief in you. It also changes the way you think about dodging developing dicey situations in traffic. While the Muscle we’re testing is equipped with the optional ABS, and that’s in addition to the industry-standard Brembo triple discs, it’s not the brakes you come to rely on when snap evasive action decisions are called for. It’s the throttle. This bike will squirt out ahead of trouble at least as effectively—and often more so—than slamming on the binders and pulling up short. That’s a nice option to have.

The Muscle also proved itself a stable mount, holding its line and soaking up the bumps on even beat-up stretches of pavement ably. In high winds it barely flinches, even in the 40 mph gusts experienced over Altamont Pass on the return leg of the journey. It’s just as stable through the twists and turns, and despite its beefy 240mm rear skin, the Muscle flicks around with relative eagerness. You can scrape hard parts, but it takes conviction.

And you thought you had a drinking problem

Suitably dressed, and with some acclimating on the part of the operator to the bike’s unorthodox ergos, the Muscle has proven an able distance runner, but it has an irritating drawback in that kind of duty, i.e., the fuel economy is poor. Really poor. A better term might be fuel extravagance, since over the course of the Laughlin trip the bike delivered an average consumption of just 33.8 mpg. Yow. On the low extreme was the high-wind run over Altamont Pass where, at an average speed of 70 mph, the bike sucked down a gallon every 28.4 miles. My Buick can do that. It’s likely that we can attribute those bleak numbers primarily to the fact that at 70 mph in 5th gear the engine’s turning at about 4700 rpm. There is no 6th gear. There should be.

Equally irritating is the misinformation about remaining fuel and range-to-empty that the Muscle’s warning light and odometer provide. The Muscle—and all contemporary V-Rods—are equipped with 5-gallon tanks, which even under the worst case scenario should be good for 150 miles. So when, for example, the low fuel light flickers on at 102 miles, and the odometer screen puts up a range to empty of 31 miles, the math is already off, and if you figure on an average 34 mpg, it’s off by a full gallon. In places like the Mojave Desert, where fuel stops are few and far between, that uncertainty becomes an unwelcome worry worm in your road brain.

Still and all…

The Muscle’s a good road buddy. Fast as stink and game for any adventure, and the real beauty of it in this application is that when you get to where you’re going, and that place happens to be someplace like the Laughlin River Run, you’re riding a machine with some serious boulevard presence, an exotic head-turner—and the damnedest bagger anyone’s ever seen.