The Netherlands’ Luuc Muis’ Indian Board-Track Replica Cuts Like a Razor’s Edge

Words by Kali Kotoski

Photos courtesy of Luuc Muis/LM Creations

We have all seen them. The big-raked choppers that look like they have metal walrus teeth chewing up the asphalt. The low and sleek baggers with large front wheels and R-rated paint jobs to accentuate the over-accentuated curves, especially in the rear. From blinding amounts of chrome to steroid-injected performance baggers and cruisers with beefed up shoulders, we all have seen them.

Sure, a lot of them are beautiful and a lot of us love them, but an overdose of the same at times makes custom motorcycles merely a soothing screensaver or posters to be hung on the shop wall, regardless of the incredible talent that goes into the build.

That is why the Hasty Flaming Buffalo by then 27-year-old Dutch designer Luuc Muis is so refreshing, even if its shaving-with-a-straight-blade-razor quality induces the anxiety of a slip to the jugular, because it certainly gets the blood flowing.

The custom Indian Scout Bobber is raw, sharp and stripped of its original design essence, something Muis’ one-man LM Creations was keenly aware of when first designing the bike for an Indian Motorcycle competition to celebrate 100 years since the bike was first produced in 1919.

“The immediate inspiration for the bike was of course the history of Indian Motorcycle, and I wanted to imply the heritage of the Scout as well as boardtrack racing,” Muis said. “Seeing it was the 100th anniversary, it was a really obvious decision and the easy way out.”

Muis’ humbleness belies the months’ worth of computer drafting design and engineering work involved with completely designing a true original. But before the lines were put on the screen he had to search the internet and history books to try to make the board track racing replica as period correct as possible.

The search proved challenging with limited archival design specifications, so Muis had to rely on old racing video clips (which are rare) and still photos of Indian’s first factory-built superbike.

“When I submitted the concept design to the judges I wanted to make sure it wasn’t just a pretty picture,” Muis said, “but a bike that could actually race if I was going to build it.”

Once the judges approved, the real engineering work began. It is one thing to build a custom bike. It is quite another to totally design a bike that strips everything away from the factory model except the 1,133cc V-twin engine and the axles.

In some ways, utilizing only the engine offered a clean slate for Muis to create. In other ways, it means every step of the build had to be methodically planned, with little to no room for error given that the build competition gave him only 20 weeks to put everything together.

“It was very difficult to design everything because almost everything is a one-off or manipulations and adaptions of existing aftermarket parts,” Muis said.

First order of business was the frame, obviously, which required virtually testing the tensile strength of the aluminum while incorporating a variety of real road factors.

“I had to consider thickness and set up to make sure the bike was actually safe to ride,” Muis said.

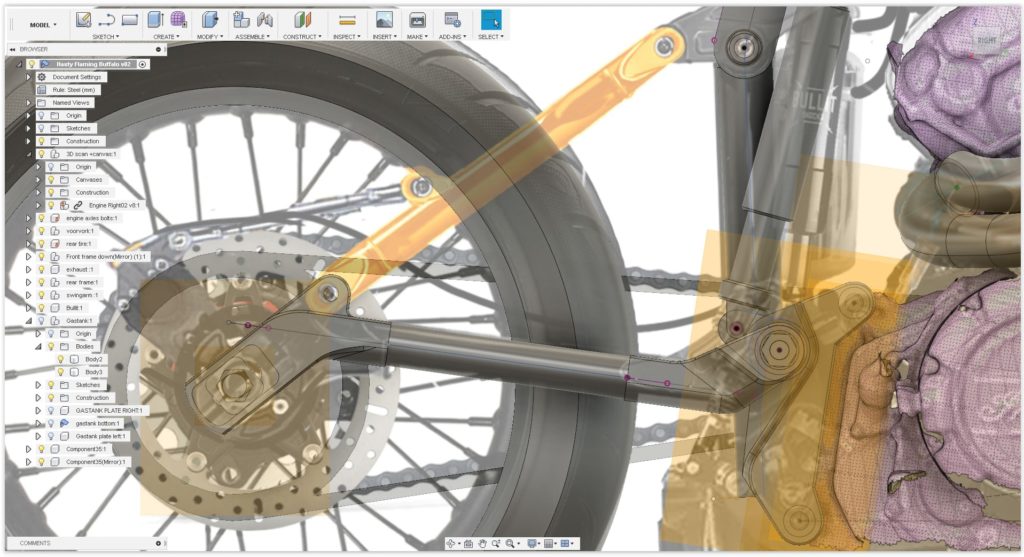

Once the frame was built, the rear suspension proved to be the most difficult task to conquer, Muis explained. He wanted to have clean lines, proper geometry and to make it a softail so it wouldn’t buck him off the saddle while ripping around the track.

He settled on a downhill mountain bike-inspired suspension, which can be much more forgiving on bumpy road conditions and provides more stability at high speeds. Up front, Muis got help from CeraCarbon Racing, which manufactured a full carbon fork and a set of diamond-cut ceramic-coated carbon fork tubes.

Along the way Muis reached out to Richard Christoph, Indian Scout Design Team Leader, over Instagram to talk shop and design processes.

“I bluntly sent him a message and was like, I am doing this competition, and he openly gave me a few pointers to streamline my process,” Muis said. “It made me feel like I had a mentor on the project, and it was really something when he told me he wished he could be doing what I was doing to the bike.”

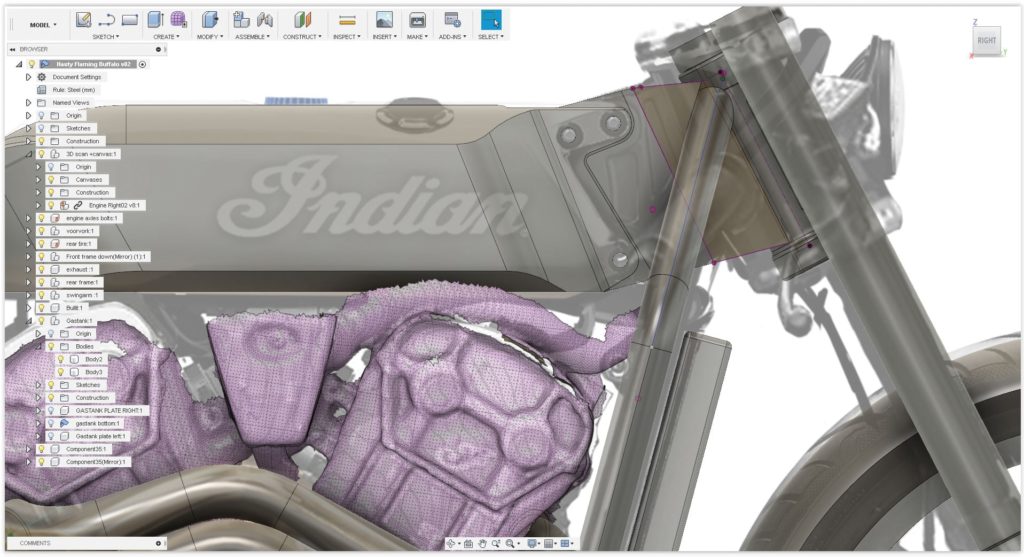

Speaking of process, Muis explained that some builders will look down on the computer-aided 2D and 3D design and engineering process, claiming ‘real’ builders build without technological assistance.

“They say engineering on a computer is just a new age thing and not a craft. But in my opinion it is a craft, and just because it comes out of a machine doesn’t mean it is less of a creative process,” he said. “Especially because it will not work without the actual skills to build it. It is all about making sure you do the first step correctly to avoid any problems along the way.”

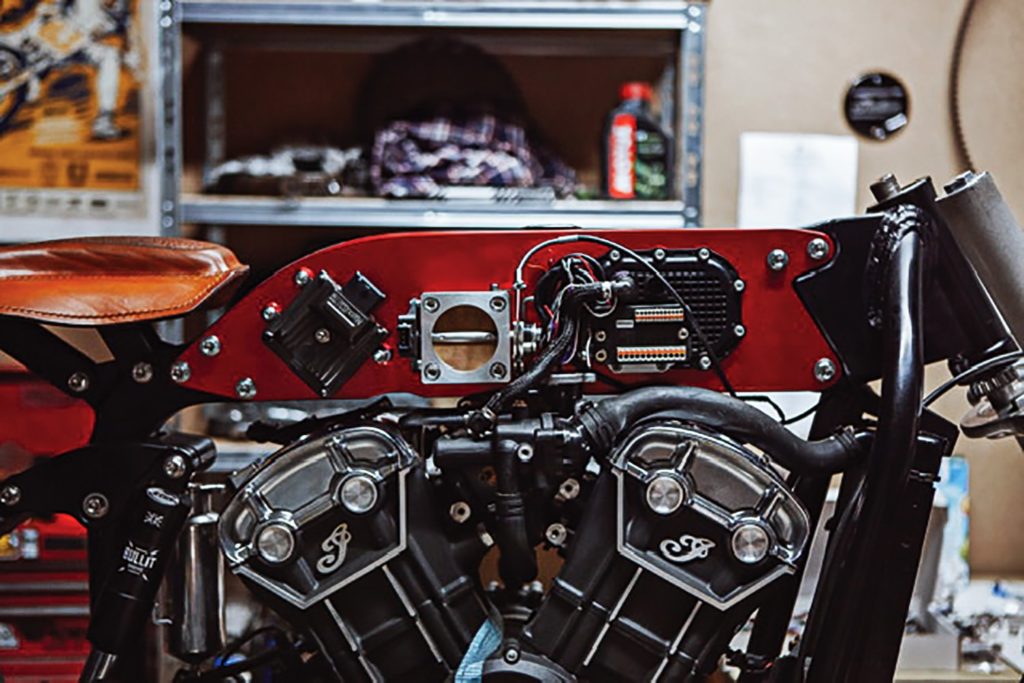

Building the sharp-lined and beautiful handmade tank was another task, as the tank literally forms parts of the frame and hides all the electronic components, air intake and air filter. Still, doing the sheet metal work “was a lot of fun because of the artistry involved,” Muis said.

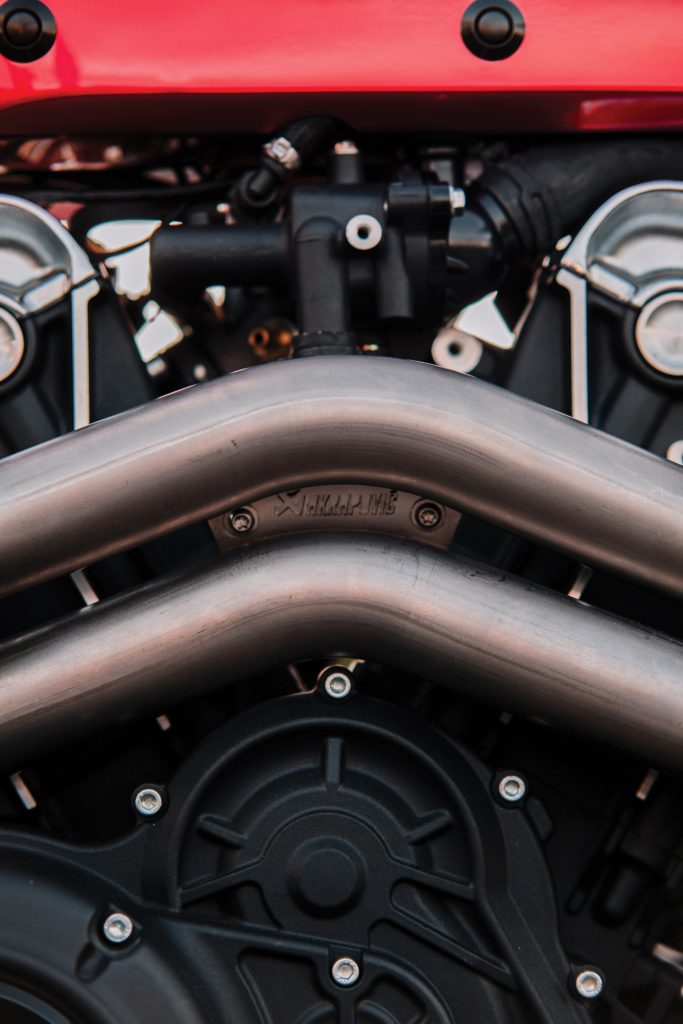

For the exhaust, Muis collaborated with Slovenian exhaust manufacturer Akrapovič, which fully dedicated itself to bringing the build to fruition. “What was great about this build was I got to go see the inside of manufacturing plants that the vast majority of people will never see in their lifetime,” Muis said.

While the bike did not run when it first debuted at the Bigtwin Bike Show in Houten, Netherlands, and won the competition, it does now. Time was too tight to get it running before the crowds were allowed to salivate over the build. This oversight will be ignored as Muis, like a lot of builders under intense make-or-break deadlines can attest to, was burnt out. Plus, he nailed a modern take of an Indian while paying homage to a long-lost sport.

“I actually hesitated if it was possible for me to complete the build because for me the opportunity was a big deal, but at certain points it almost broke me,” he said. “Luckily, I have a really lovely girlfriend who would bring me food because after my eight-hour day job I would work eight hours at night on it. That is fine if it is only for two weeks, but it was for 20 weeks and that gets really crappy.”

Once the bike show tour was finished, Muis had the time to tackle the ECU and tune the bike with the help of a drag racing friend.

“I procrastinated a bit with the ECU because of the complexity of it. But what ended up happening is I had to dumb the ECU down to operate on just one sensor, instead of the typical four or five sensors,” he said.

The bike rides really well, Muis explained, being rough as expected for a bike that looks the way it does.

“It is loud, noisy but clean, and you can feel it wants to push you and wants to go fast because with the ECU hardwired in, it does everything you put into it,” he said. “At low RPM ranges it is really bad, but once you get it above 3000 RPM it just keeps going and going.”

It keeps going so much that Muis had to take the top RPM down from 9000 to 8500 RPM.

“We don’t know what the top speed is, but it is really powerful,” Muis said. “When we first put it up on the dyno it was putting 107 horsepower out of the rear wheel, and we see a 25 percent increase in torque because more air is coming in.”

Even his friend that drag races 700-horsepower bikes is impressed with how it performs on the track, Muis explained.

“My friend says it isn’t as crazy as what he races,” Muis said, “but it is definitely a crazy ride, and an impressive jump forward in terms of power.”

Looking at the thing, we can certainly believe that.