STURGIS, S.D., AUG 3–Indian Motorcycle knows how to draw a crowd, and they know how to keep a secret. That much was apparent when at long last the company unveiled their 2014 lineup of models to an overflowing sea of onlookers at the Sturgis Motorcycle Museum at the corner of Junction and Main Streets, the geographical and spiritual heart of the Sturgis Rally—which not coincidentally was started by an Indian dealer, Clarence “Pappy” Hoel and his Jackpine Gypsies MC 73 years ago, making for a poignant historical tie-in to the location for the unveiling.

There was the distinct sense that the tidal wave of hype and heightened expectations engendered by an eight-month campaign of teaser events and videos, as well as a series of print ads—and now TV spots as well—mocking Harley riders had finally crested and broke over the proceedings with the trotting out of not one, not two, but three variations on the Chief theme, the third one—the Chieftain—being the real stunner that nobody seriously anticipated.

The build-up to the evening’s event had picked up serious momentum back in March when the company displayed and ran the entirely new Thunder Stroke 111 motor at Daytona Bike Week. Both the motor’s appearance and mechanical details were impressive and enthusiastically received by motorheads and Indian traditionalists alike, but that’s all they would get until the official rollout of the completed machines slated for Sturgis Bike Week.

When the day arrived and the new models were ridden by several notable personages (including Polaris CEO Scott Wine, Buffalo Chip proprietor Woody Woodruff, American Picker and Indian pitchman Mike Wolfe, famed racer Don Emde, and LSR racer and industry stalwart Laura Klock) onto a runway erected in front of the museum there was a crush to the stage to get a closer look and appraise the goods, followed by a surprisingly swift dispersal of the crowd, many of whom had come to the hasty conclusion that the new Indian was, visually at least, just more of the same Gilroy/Kings Mountain-style skirted fender behemoths. And as a first-blush reaction that was understandable—from a distance the new Chiefs look eerily familiar—but in reality, and as we would discover over the next three days of road testing and tech briefings, they could not have been more mistaken.

When Polaris Industries purchased the marque from Stellican in Kings Mountain, North Carolina, they got the whole enchilada of trademarks, logos, proprietary design and engineering properties, and as much of the production facilities and staff as they cared to cart off. They immediately made it clear that the trademark and the famous war bonnet were what they were truly after. Even so, they mustered out a number of tepidly-received Kings Mountain-style specimens the following years to essentially keep the name in play and preserve whatever market momentum the marque may still have enjoyed. But behind the scenes, the Polaris/Victory team was rolling up its sleeves, pulling out a clean sheet and embarking upon a whirlwind 26-month reinvention of the breed. A daunting task, for sure, but one that they pulled off admirably.

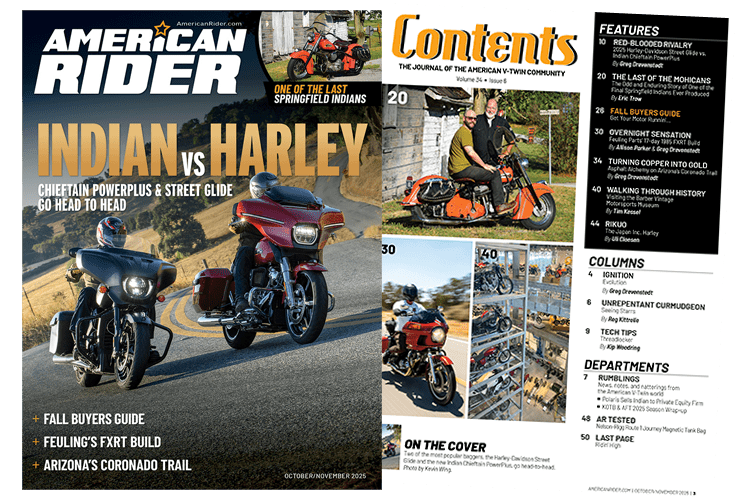

The three models introduced for 2014 are the Chief Classic ($18,999), the essential cruiser without touring accessories; the Chief Vintage ($20,999), a tarted-up version of the Classic that adds a substantial windscreen, crash bars, leather saddlebags and oodles of fringe; and the aforementioned Chieftain ($22,999), a different animal altogether in many salient respects. As you’d expect, the three models share a great deal of componentry and cosmetics in common, and the close connection between the new Indian Motorcycle and its corporate sibling, the 15-year-old Victory Motorcycles, is in abundant evidence.

Take for example the chassis of the new bikes. It consists of seven cast aluminum sub-members that connect to form a rigid backbone of a frame. The second segment of the assembly also serves as an intake and plenum for the fuel injection system, and all of those features come directly from the Victory Vision/Cross Country/Cross Roads playbook. Taking that technology a unique and welcome step further, the new Indians feature a single removable pin that lowers the entire rear suspension assembly facilitating less fettered access for changing the tire without having to remove that massive skirted fender.

A large spring-over monoshock with a rising rate link under the seat, electronic throttle, with ABS and cruise control standard on all three models are additional benefit derived from the long Victory development curve.

The influence of Victory on the Indians is especially glaring on the surprising new Chieftain, which the company points out parenthetically is the first hard-bagged, fully-faired motorcycle to ever sport the Indian name. That model’s high-tech cockpit, electronically adjustable windscreen, and spacious, user-friendly panniers bear unmistakably the genetic code of the Victory Cross Country.

Also common to the three Chiefs are a keyless ignition system, auxiliary light bar, leather saddles and a limited color palette consisting of Thunder Black, Indian Motorcycle Red or Springfield Blue. The colors all have a deep gloss but no metal flake or pearlescent confections—and it’s an effective approach for highlighting the bikes’ extensive chrome plating and the subtle sculpting of the bodywork.

That motor

The technical highlights of the new Thunder Stroke 111 motor were covered extensively by Technical Editor Kip Woodring in our April edition, but to recap the high points, it’s a 49-degree pushrod-actuated V-twin with three cams, automotive-style “straight shot” valve train and wedge combustion chambers (and if any of this reminds you of the S&S X-Wedge engineering, it’s probably no coincidence). A single-piece 2″ crankshaft is driven by slender, lightweight side-by-side “fracture” cap-style con rods.

Power is transmitted to the final carbon-fiber reinforced belt drive via a massive direct-drive wet clutch and 6-speed transmission with helical-cut cogs in all but first gear. A helical-gear counter balancer keeps the vibration level well within livable limits from an idle to WFO.

And, of course, there’s the look of the thing, which with its left-side intake, stout pushrod tubes, heavily finned valve covers, and down-dump exhaust pipes presents a remarkably true evocation of the 80″ side-valve Indian mills of the late Springfield era.

Among the toughest engineering challenges, and top priorities, for the motor design team was dealing with the inherent heat accumulation properties of the downward exhaust setup. They addressed it with sophisticated port design, ceramic-coated double-wall headers, a heavy application of cooling fins, and a 5.5-quart oil supply routed through a front-mounted oil cooler.

Slowly we go

The effectiveness of all those heat management countermeasures proved out almost immediately, thanks to an ill-advised—but ultimately revealing—press ride through the Black Hills two days later. As any Sturgis veteran knows, Monday afternoon is the absolute time to be out hitting the major tourist attractions of the southern Hills, and that’s because Sturgis is flooded by bikes arriving and setting up camp or whatever other accommodations they’ve arranged on Sunday of Rally week. The entire state of Minnesota, in fact. And the first thing they all want to do on Monday is tour the Needles Highway, Iron Mountain Road with its one-lane tunnels and pigtail bridges, drop in at Keystone and head out to the Faces. ’Twas ever thus.

But that was our route, and it was undertaken in humid 80-plus degree conditions, finding ourselves in stop-and-go traffic—especially at the single-lane tunnels and through the famous Eye of the Needle defile on the Needles highway.

By rights, you’d think the Thunder Stroke 111 would be a molten mass after hours of that kind of abuse, but it never lost its cool—though cool is a relative term when discussing any air-cooled motor. Not once did the heat from the rear exhaust reach the point of burning my right leg, like you’d reasonably expect. And not once did those conditions bring on even a hint of pre-detonation like you might also reasonably expect. Even in those heinous conditions the mill remained poised, confident and ready to take a quick twist of the throttle. The motor boasts an impressive 119 ft/lbs of torque, and it’s delivered over a broad swath of the rpm band—a significant departure from the 105″ Powerplus motors of the previous recent iterations of the brand.

Badlands drifter

Free at last on the third day of testing to break from the constraints of the group program and have my way with one of the new models, the touring-outfitted Chieftain was a no-brainer choice of mounts, and a long cruise out to the Badlands on lightly-travelled Route 44 past the now-ghostly town of Scenic (now owned by a Filipino church, of all things—and the buildings boarded up, sadly) and then a free meander through the otherworldly landscape of the Badlands seemed just the ticket.

The fully dressed Chieftain is indeed a creation distinct from the others in the stable and the differences are more than skin deep. The forward steering head section of the seven-piece backbone chassis has been swapped out for one with a steeper rake, giving the Chieftain 25 degrees as compared to the 29-degree rakes of the Classic and Vintage. It’s also been given an air-adjustable monoshock in the rear and some additional travel—4.49″ as opposed to 3.7″. A lower profile rear tire is used as well, and cast wheels with black sidewall tires are employed instead of chrome spokes and whitewalls. Bluetooth capability and an easily-manipulated sound system are included. A dazzling menu of on-the-fly monitoring of fuel economy, ambient conditions, time on the road, oil change interval alerts and tire pressure monitors are there to be scrolled through with a trigger on the backside of the left-hand switch module, and a like trigger on the right-hand side serves as a dash-light dimmer. My only quibble with the setup is that, like one in five or six males, I have some red-green color blindness that renders the pink-hued readouts virtually invisible with the naked eye and utterly invisible with shades on. I pointed it out. I received an open-minded response that this was, indeed, something they’d be taking a longer look at.

Rock steady and turbine smooth right up to the ton—which it achieves in a hurry—the Thunder Stroke 111 exudes bring-it-on confidence and pulls lustily from its deep well of torque jumping eagerly from 25 mph to highway speed in third gear with a twist of the throttle. Its 119 ft/lbs of torque surpass both Harley-Davidson’s TC103, at 100, and Victory’s own Freedom 106, which boasts 106 in its touring configuration.

And that windscreen. Put simply, it’s the best one out there, even if it weren’t electronically height adjustable (thanks, Victory Vision). It appears a modestly proportioned shield when viewed at its lowest setting, but even at that height protects a rider of even my 6’4” stature effectively while providing a completely unobstructed over-the-top view of the road ahead. With inclemency or hyper-legal rates of progress, running it up to its highest position cocoons the operator admirably.

My Badlands lark covered 200 miles, and it was at stops such as Scenic that the Chieftain really attracted interest from other riders. I found myself conducting impromptu tech presentations on the bike’s features and performance, and running the windscreen up and down as a visual aid. As a final treat I left town in a burst of 0 to 60 exhibitionism to demonstrate the motor’s stirringly sonorous growl of an exhaust note.

Forward-looking statements

Three eminently—even surpassingly— capable and likeable new models supported by the deep, deep pockets and elaborate design and engineering resources of Polaris Industries bode well for the ultimate revival of the Indian marque, but that’s not to suggest that there aren’t imposing challenges in carving into the overwhelmingly dominant market share of big-bore street and touring machinery that is the province of Harley-Davidson—without inadvertently cannibalizing their own Victory consumer base. In the immediate term, two come to mind, the first being the relative paucity of designated dealers, and parts and service availability. Indian projects a network of between 125 and 140 dealerships by year’s end, though they’re vague on the question of whether Victory dealers will be a primary source of the outlets or whether stand-alone purveyors might be the wiser option. Either way, that’s a relative handful in the big picture—but one that’s bound to increase as the Indian story plays out.

Of equal concern is how far Indian can stray from the valanced fender look that dominates the brand’s styling, and has dominated the styling of its ambitious but futile precursors over the recent past. After all, it was that styling element that came late in the Springfield game and lacked sufficient allure to keep the original Indian solvent. Still, it’s hard to imagine how they could have launched the current revival without that now-signature detail. Whether or not they find themselves circumscribed aesthetically by their own fenders going forward will be of great interest, and could prove pivotal in their ultimate success.

Despite the oft-expressed opinion that the Indian marque has been beaten into insignificance by over half a century of pretenders to the war bonnet, it still exerts a powerful tug on the American moto-soul. I know it does on mine. Both my father and grandfather rode Indians. The original Springfield company went under in 1953, the year of my birth. So, yeah, even as a to-the-bone Harley fancier I feel the appeal. And as a final footnote to that thought, my final stop on my Badlands Chieftain ramble was at the rest stop outside Rapid City where an octogenarian named Roy Savage was manning his Baptist church’s free water and coffee stand. When he saw me arrive he hustled over to inspect the machine. As it developed, he was a lifelong motorcyclist and Indian racer and he commenced to regale me with stories about racing on the sand in Daytona Beach back in the day, including an anecdote about helping the legendary Ed Kretz pull his Indian out of the surf and get it fired up again so he could complete the circuit. Roy was still riding at his advanced age (a Honda PCH, as it were) and he asked me if this new Indian was available for a test ride. I told him where the demo site was located and he said he’d head over there and get his name on the list, allowing that there would probably be a long wait. But he was game to give it a go, nevertheless. He was in earnest. I was in awe.