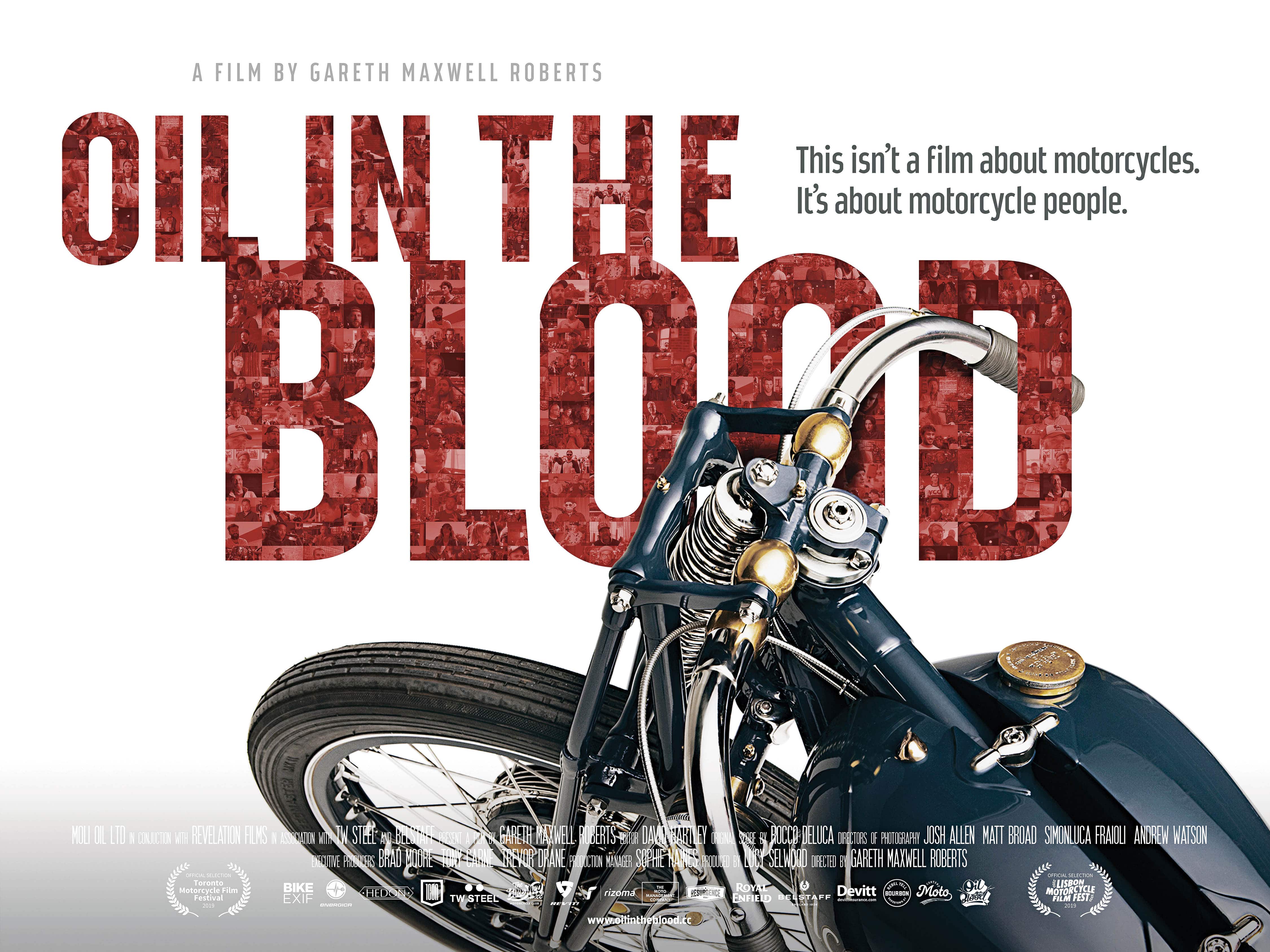

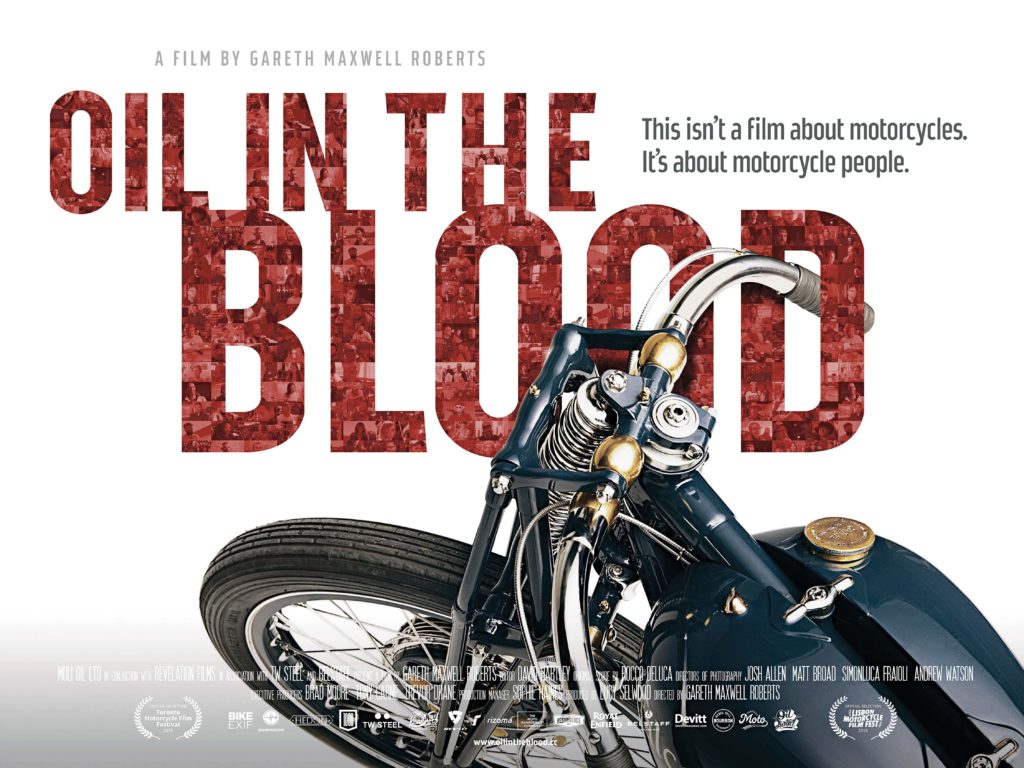

A New Documentary Takes Viewers Into The Fascinating World Of The Modern Custom Motorcycle Scene and Its’ Avant-Garde Builders

Words by Kali Kotoski and Joy Burgess

Photos supplied by Gareth Maxwell Roberts

A new film by Londoner Gareth Maxwell Roberts explores the personalities driving the current revival in the custom motorcycle scene. It is a scene without rules or labels and stays on the fringes of the mainstream. In some ways less hedonistic than building trends of old, it is primarily utilitarian at its core—and manufacturers have taken notice. Crisscrossing the globe for over three years, Roberts interviewed more than 300 builders in order to portray the creativity that goes into some of the hottest modern builds. What started as a small niche of bespoke builders has evolved into a global phenomenon, which will certainly keep the blood flowing for years to come.

Reviewed by Kali Kotoski

OK, Boomers. If you have had your head stuck in the sand for the last decade, you have likely been missing one of the most exciting things to happen in the custom motorcycle scene. Mainly, the revival, the revolution of the custom art form, spurred by a growing interest in flat track racing, the societal fallout of the Great Recession and the raw individualism of us hipster snowflakes that never had 401(k)s or IRAs to gut-wrenchingly watch $2.4 trillion in collective savings vanish. And, you would have likely missed the news that Playboy is now run by a large majority of female editorial staff in their twenties.

Motorcycling has always been about rebelling because motorcycles make little sense. The common belief is that the spirit of riding is dying, sales are hurting, and the “youth” have little interest in the sport and that they would rather receive a guaranteed universal basic income to spend on video games and craft beer.

But, the documentary film Oil in the Blood is here to tell you not all is lost and the free-wheeling motorcycle spirit has merely been passed down to us young ‘uns. And we have taken that spirit, retooled it and made it our own … and then post it on Instagram and social media, anticipating an online thrashing.

Gareth Maxwell Roberts’ lengthy treatise on the custom revival, available on Amazon, captures the purity of individualism and innovation despite financial constraints. And, likely, none of those individuals care which bathroom you use. All they care about is two wheels.

With the movie’s vivid riding scenes, from the Sahara on a Harley to England’s countryside on a sleek Ducati to ice racing somewhere in the inhospitable Midwest, Roberts takes you on a journey to some of the coolest bespoke shows across the world. He interviews modern-day luminaries like Ian Barry of Falcon, Max Hazan, Craig Rodsmith, Walt Siegl, Shinya Kimura, Winston Yeh of Rough Crafts, Ola Stenegärd of Indian and Kurt Walter of Icon Motosports.

The message conveyed is that despite rabid consumerism, technological advancement (yes, iPhones are killing our eyes and ADHD is the clinical norm) and the perverse ideal of instant gratification, thousands of young bikers still love the smell of oil, the heat of the welding torch and the smooth feel of a well-sanded fuel tank. The movie is 100 percent motorcycle porn with a tasteful art house feel.

But the movie is really about the people building these amazing bikes and their individual beliefs, with the common thread of revolting against, but not overthrowing, the MANufacturer. It shows a custom scene that has been fully democratized without traditional constraints or expectations. It is also about the simple pleasures of Hooligan and drag racing; a nexus between function and form. The movie is about those builders that build to ride, not build something that will collect dust between shows. Spend $1,000 or $100,000, if it rides you are part of the club.

Remember, we were all cool once, crafting our identities by rebuilding a carburetor, throwing on some sick custom parts, adding cool paint and saying, “yep, that bike is mine.” Oil in the Blood shows that spirit is alive and well, and, god-willing, will endure until the internal combustion engine is retired. Then, that same spirit will trick out an electric motorcycle.

So, if you want to check out a flick that shows an industry booming with creativity and one that gives hope among the continued doom and gloom of manufacturers’ financial earnings, I suggest you check it out. Sure, in typical hipster fashion if too many of you watch it, the scene will no longer be cool. But there is always the next cool thing yet to be discovered.

Reviewed by Joy Burgess

Motorcycles grabbed my heart and changed my life a few years ago (another story for another time), and in the past year I stumbled right into the middle of the custom scene. And I’m hooked. Custom shows like The Golden Bolt started a spark. Talking to custom builders like Brian Buttera (The Golden Bolt winner), Caleb Denton (Born Free invited builder), and customs guru Kevin Dunworth fed the flames. And then, watching the film Oil in the Blood set me ablaze.

Custom motorcycles get me excited. But it’s not just about the bikes, as awesome as they are. It’s the people involved in the custom scene that captivate me. These are the people who have fallen in love with motorcycles, who have a vision for what they can make out of them, and who, when they couldn’t find what they wanted, built their own. They’re the creatives in the motorcycle industry – the very heart and soul that’s driving the industry right now.

And that’s what the documentary Oil in the Blood is all about – the people involved in custom culture. From the moment I saw the first trailer, I knew I had to watch it. When it finally made its way to Amazon in the U.S., I sat aside my evening to watch it. And while the run time of over two hours might look daunting, it was worth every minute. The last time I got goosebumps watching a motorcycle film was the first time I watched On Any Sunday, but within the first few minutes of watching Oil in the Blood, I had goosebumps.

I immediately loved that the film didn’t focus on just the UK or the United States, but it truly followed custom culture around the world, including the thriving chopper scene that exists in Japan. It’s easy for us to get caught up in what’s happening in the American V-Twin market, but the globalization of the custom scene – fueled largely by social media sites like Instagram and YouTube – fascinates me. As I’ve talked to custom builders here and there for Thunder Press, I’ve quickly become aware of this unique network that exists among these builders, and I saw it displayed prominently in this movie.

One thing the movie really drove home for me is that custom culture makes motorcycles a lot less about the money, something that grabs my attention and the attention of other young people, I believe. As Andrew Almond of Bolt London noted in the movie, “It’s less about money and budget and what you can afford than what you can do. People spend their time doing stuff, learning stuff, actually living motorcycling.”

The film also digs into how the motorcycle world is changing because of the custom scene. Custom bikes bring people together like never before. “You’ll see your Fortune 500 CEO sitting right next to a Hell’s Angel guy, and both of them are appreciating the same thing. You’ll never see them in the same context other than that,” said Tim Harney of Tim Harney Motorcycles.

And I think that’s what struck me the most about the film. The breaking down of barriers within the motorcycle industry. Because at the end of the day, we’re all just people who love motorcycles. Whether we prefer flat track bikes, café racers, or choppers (or something else entirely), we’ve all got a little oil in the blood. So, if you love motorcycles, give Oil in the Blood a watch. And I hope you get goosebumps.

Behind-the-Scenes with Oil in the Blood Creator Gareth Maxwell Roberts

Tell us a little bit about your background in the motorcycle and film industries, and why you’re so passionate about motorcycles.

I’ve been riding since I was an early teen, and I’ve been a producer and director here in the UK for 30-odd years. Started in music videos and TV commercials and then moved into independent feature films. But I always kept these things very separate. Bikes were my antidote to work. They’ve always been a way to escape from all that shit at work.

What made you decide to make this movie, and when did you start planning the film?

When this whole custom culture took off, I was a man in my early 40s suddenly being thrown back into the whole culture of motorcycling again. I found it really curious. A little strange, but great. I felt like we were living through the best of times, a revolution, a renaissance, and I felt it needed to be documented in some way.

I thought someone needed to make a film that gave an overview of what this culture is as a whole. That’s the genesis of it really. I just decided, fuck, I want to get this done. I pitched it to the company I was working for at the time, and my boss said yes. So, we got started in the summer of 2015.

How much effort did this documentary take to complete?

Starting in 2015, it took six months to do the planning, work it all out, and get our first chunk of financing in place. We started shooting in January 2016, and we shot for about two and a half years, editing as we went along. Originally, we planned to do it all in a year, but it took twice as long. But, because it took longer, it helped me and my editor really get to the bottom of what’s important and enduring about the culture. And that, I think, made the film stronger.

How did you select the bikes, builders, and other experts you featured in the documentary?

It started with a short list of people I knew, and people I thought were significant players for different reasons – history, contemporary, and design reasons. But it quickly escalated and we ended up speaking to more than 300 people. I didn’t get to speak to everyone I wanted to, but at some point we had to draw the line.

Who do you think the main influencers are in custom culture today?

One thing I found refreshing is that I think the age of influencers is over. When this whole kind of contemporary custom culture resurged about ten years ago, it didn’t have a set of rules or a prevailing aesthetic. People were still finding their way. People who had never been involved in custom culture looked to influencers to guide them. But in the past three or four years, we’ve reached a kind of maturity. People have their own ideas and opinions, they’ve become knowledgeable enough to make their own decisions, and I think that’s great.

“At the end of the day, nobody is listening to manufacturers anymore,” Gareth commented, “And the good builders do whatever they can to make their bikes so far out there. A classic example is the bird cage bike.”

What social or economic factors do you feel led to this renaissance?

Three things collided to kind of kickstart this renaissance. First, the financial crisis of 2008. People lost their jobs. They couldn’t get credit to buy new bikes. Friends of mine who’d been riding for years had to sell their new, expensive bikes because they needed the money. Second, because of all that, people started to pick up cheap bikes and work on them. They had the option to do an expensive, expansive restoration, or just do a little bit to make the bike look cooler. Third, was the proliferation of broadband. People suddenly could share high-quality photographs on the internet and show videos. The blog sites really took off, so people could work on a cool bike and then post about it. Suddenly, the amount of references out there for modifying and customizing bikes exploded.

What was the biggest thing you learned while making Oil in the Blood?

The biggest thing I learned was that there are a set of underlying values that drive this scene that is quite timeless and enduring. I thought the culture was more age- and day-specific or transient. But the more I spoke to people across the world from all different backgrounds and angles, they all had this universal set of values, and I was really heartened by this. There’s the worry that this thing might run out of steam or run its course, but at the center of all this is a coherent set of values that will always be there. People will always be working on, modifying, and changing bikes. It’s encouraging in a day where our lives have become increasingly consumerist and we treat everything an appliance. We buy new appliances, wear them out, throw them away and get a new one. This culture bucks that trend. A bunch of 20- and 25-year olds are finding motorcycling cool again, and that means that motorcycling as a culture has a new generation that’s engaging with it. That should be celebrated.

Where do you envision the custom motorcycle scene going in the future?

In the first part of this decade, you saw this culture taking hold, and it exploded. I think it’s reached a fork in the road now. On the one side you have the retro heritage lifestyle culture being fed now by manufacturers like Harley, Scrambler Ducati and Triumph. Essentially taking stock bikes and adding bolt-on modifications, but they’re not really custom bikes – they’re the easy solution.

The other fork is people who are genuinely interested in custom bikes. It’s become more of the sophisticated folks who have levels of engineering, fabricating, and painting skills, as well as ambition. It’s almost become professionalized in that sense.

Some people have mentioned the movie is quite long. What’s your response to that?

I had a few people say the film was too long, and I said, “Yeah, it is long.” We got it down to this length and we really couldn’t have got what was in the film any tighter. We would have had to pull out a whole subject or event, and we thought if we took any out, the film would be incomplete. And if it’s a bit long, people can pause it for an hour, go have a beer, sit down, and then watch the rest of it.

What kind of feedback have you already encountered on Oil in the Blood?

When you release a film, you brace yourself for that. But I’ve been surprised by the lack of negative responses. Overwhelmingly, the response has been very positive, and to me, that’s mission accomplished. The most encouraging thing I’m hearing is that people feel that this is a film about us. Probably the biggest compliment for me was when Miguel Angel Galluzzi, the man who designed the Ducati Monster, came up to me after the screening and said, “This is the new On Any Sunday.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.