The inception of the Harley-Davidson and Indian Motorcycle wars began at the turn of the 20th century and continued through and beyond the first World War. The motorcycle market constricted due to the availability of relatively inexpensive cars and then the gloom of the Great Depression, which limited disposable income.

Related: Harley-Davidson vs Indian Motorcycle Part 1

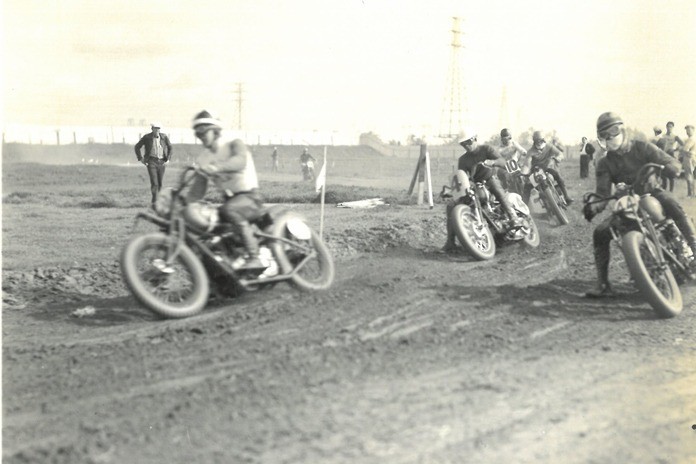

Harley and Indian fielded race teams to prove their machines were superior and show fans that they were worth riders’ hard‑earned money. Spectators watched as racers displayed their skills aboard ever‑faster motorcycles. Racing became an insiders’ circus, with outsiders as the spectacle‑loving rubes.

After Excelsior‑Henderson folded in 1931, it came down to just Indian or H‑D. For spectators, it became who to root against as much as who to root for. The sharpening of sporting loyalties between fans of both marques erupted into a bitter rivalry. America’s worst financial crisis also coincided with the peak of the Harley‑Davidson and Indian wars.

The American Motorcycle Association had dual professional racing programs. Class A was for pure race machines, while Class B was for heavily modified bikes. They both lacked a deep field of competitors, so the AMA hatched an idea for a more accessible class.

The new “production” Class C rules initially featured several novel requirements. The machines were to be side‑valve Twins up to 750cc or overhead‑valve Singles of no more than 500cc. They had to be stock and street‑legal with lights, a horn, and everything else. They also needed to be owned by the racer, ridden to the track, raced, and then ridden home.

Harley’s model D that debuted in 1929, the so‑called “3‑cylinder” because of the bike’s vertical generator, evolved into the more powerful R series by 1932. It was better able to compete – both on track and in the showroom – with Indian’s Scout 101 and the freshly minted Sport Scout.

The first full season of Class C racing was in 1934 and shaped up as a remarkably even contest of quality versus quantity. There were more Harleys and fewer (but usually faster) Scouts. Proving that riders mattered as much as mounts, amateur racers swapped wins all season. It was great entertainment and provided a lot of parity, so it caught on.

Class C racing worked out well because it was good for spectators and participants in equal measure and helped sell bikes as the economy improved in fits and starts. In contrast, professional racing was boring, with only one team rider, Joe Petrali, winning every race for H‑D on a 350 Single in 1935, causing the pro ranks to peter out.

The rest of the 1930s was a sort of see‑saw series of events. E. Paul duPont pulled Indian back from the brink while the MoCo developed something new in hopes of a brighter future. H‑D’s V‑series Big Twin got sorted and was made larger (80ci), and it started selling. The 45ci R‑series begat the W‑series with many improvements.

Indian made their Big Twins prettier and faster, and the Chiefs outsold the Scouts even though the various versions of the Scout were highly promoted.

Knucklehead | Harley-Davidson vs Indian Motorcycle

Bill Harley and the three Davidson brothers were no longer young men when the decision was made to build an all‑new OHV Big Twin. Considering the dire straits of their company’s finances, not to mention the shaky circumstances of the Depression, it was as foolhardy as it was brave – a gamble that became a legacy.

The 61ci E/EL models were aimed at the experienced enthusiast who wanted something akin to a grand‑touring automobile: sophisticated, comfortable, swift, and capable of covering ground effortlessly, even two‑up with baggage. After all, new roads were everywhere, with more being paved every year, and the need for a “Gentleman’s Express” type of motorcycle was burgeoning.

Dealers and a select few others knew about the impending arrival of the new machine, but there wasn’t one word about it in the 1936 brochure. Harley soft‑pedaled the 61 OHV, letting the bike speak for itself. In its 1937 brochure, the company stated: “When this model quietly made its appearance here and there late last season, it created enthusiasm never equaled in the history of motorcycling.”

Hyperbole aside, from the “cat’s eye” dash to the 4‑speed constant‑mesh transmission, the styling, design, colors, and detailing were proof this motorcycle was right for the market. It also didn’t hurt that a redesigned version of the Indian Four, the so‑called “upside down” Four, didn’t go over well.

H‑D operations experienced significant changes in this era as well. It sold the rights for manufacturing Harleys in Japan to Rikuo, its workforce became unionized, and William Davidson passed away at the age of 66 on April 21, 1937.

Star Racers | Harley-Davidson vs Indian Motorcycle

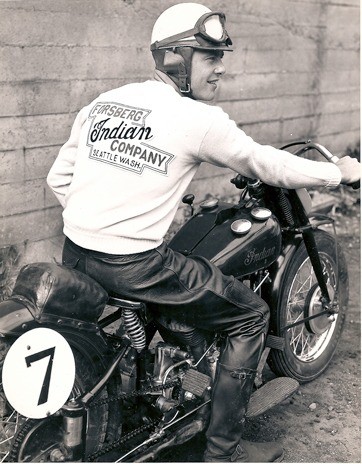

This was the era of stars like Shirley Temple, Sea Biscuit, and Babe Ruth. Motorcycle fans had Joe Petrali, Sam Arena, and the irrepressible “Iron Man” Ed Kretz.

Kretz came on the national scene with a spectacular win in 1936 at the 200‑mile race in Savannah, Georgia. He jammed his Indian around the track to take the win and raise the average speed for the race by 10 mph. Then there was his win at the first Daytona 200 in ’37, where he fell off twice and still lapped the entire field of 86 riders.

In March 1937, H‑D set its first land‑speed record with a special twin‑carb, full‑race version of the Knucklehead. Petrali rode it to 136.18 mph on Daytona Beach, beating the American record of 132 mph set by a special 61ci 8‑valve Indian in 1924. Petrali’s record stood for 11 years.

In 1938, Kretz again amazed spectators during the 200‑miler at Laconia, where he fell off and jammed sand into the carb. Fixing the problem cost him 15 minutes in the pits, and then he lost his left footboard after 50 miles, so he had to place his steel shoe on the primary drive. Despite tearing three layers of skin from his hands trying to control the unruly beast, he turned the last lap faster than the first and won the race. When Kretz retired from racing in 1959 at the age of 47, he was the oldest contender in a young man’s game – a game that never paid him more than $1,100 for a win.

Sam Arena was an equally effective track threat from Harley‑Davidson. The mods applied to his bikes by legendary tuner Tom Sifton allowed Arena to keep the throttle pinned throughout the 1938 Oakland 200 race in California, a feat undreamed of until then. The result was a start‑to‑finish win that beat the previous record at that track by 17 minutes!

These were bright spots in the Depression’s dark times that helped make things better – until December 1941, that is.

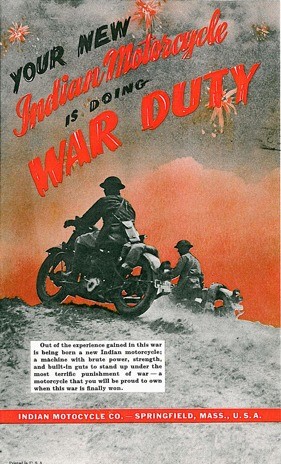

War Efforts | Harley-Davidson vs Indian Motorcycle

World War ll affected the country in every possible way. Once rationing kicked in, rural motorcycle dealers were hit hard, and plenty of them shut down for the duration of the conflict.

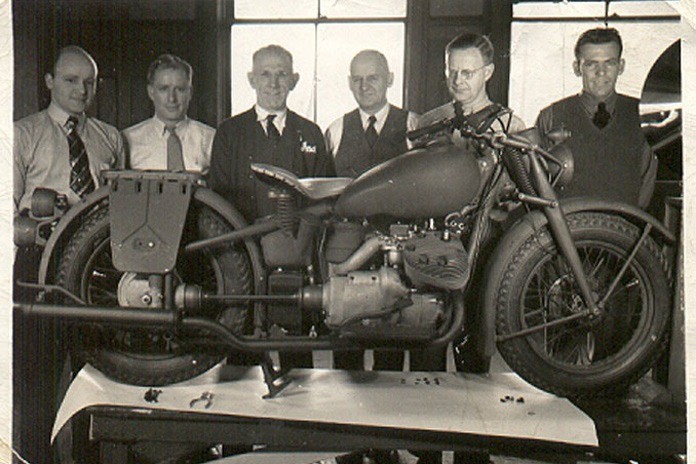

For the American motorcycle industry, another World War guaranteed sales on a 10% cost‑plus basis. Almost at the outset, the U.S. government approached H‑D and Indian about building machines to match the Wehrmacht BMWs. They also authorized 1,000 experimental examples from both companies.

Harley cranked out more than 80,000 45ci WLAs and also developed the military XA. It mimicked BMW’s excellent BMW R71/75 with cylinders opposed across the frame in a “boxer” layout and was H‑D’s first and only shaft‑driven motorcycle.

Indian cleverly came up with what might have been the inspiration for the post‑war Moto Guzzi: the 841, a 90‑degree V‑Twin set across the frame. Both H-D and Indian used shaft drive on their experimental machines at the request of the War Department.

Worn‑out tooling from the 1920s was a problem for both companies once production ramped up to nearly three times what it had been. H‑D production initially was hindered because Harley had rented out part of its Juneau Avenue factory.

Many claimed stress was to blame when Walter Davidson died on Feb. 7, 1942, at the same age as his brother. The mercurial, iron‑fisted leader of the Motor Company had been a steady hand on the tiller at H‑D for 35 years. In many ways, it was Walter who waged an undeclared war on any motorcycle maker he perceived as a threat.

In 1943, George Hendee, co‑creator of Indian, quietly passed at the age of 76. A few months later, William Harley died of a heart attack. These men, who had been there from the very beginning, made motorcycle history and left indelible marks on the American motorcycle industry.

War production for Harley‑Davidson amounted to 89,000 WLA and WLC models and enough spare parts for nearly 30,000 more. Indian built 42,000 machines: mostly the 500cc 741 model, but also 340/344 sidecar rigs, 841 models, and the 45ci Scout‑based 640 series, plus gobs of spare parts. Additionally, about 3,000 bikes went to France for “essential” purposes in Europe.

In the spring of 1944, with the tide of the war turning in the Allies’ favor, all open‑ended military procurement orders were canceled, leaving things in a messy situation. Thousands of machines in Europe and here at home were suddenly “surplus.”

In the U.S., 15,000 H‑Ds and 7,500 Indians were offered for sale in batches of a dozen. Dealers snapped up most of them, with a Harley dealer in Santa Ana acquiring a lion’s share. The same thing happened a year later, with 10,000 out of 15,000 Indians offered going to Canada and some of those sent to Britain. Much of Indian’s surplus was also shipped to Russia, Australia, and New Zealand.

Post‑War Era | Harley-Davidson vs Indian Motorcycle

Once the war ended, the pent‑up demand for cars meant the auto industry could sell everything it could build. Auto production cranked up so fast that the total production by all makers at the end of 1946 was estimated to be a stunning 6.8 million!

Meanwhile, there was a worldwide glut of surplus motorcycles. With so many motorcycles and not so many riders, the battle for the future of American motorcycling would be to find a way of getting more butts on the seats of motorcycles. Stay tuned for our next chapter as we examine how motorcycle companies navigated the post‑war era.

Great article by Kip Woodring on Harley Davidson and Indian motorcycles

Glad you liked it! Kip does great work for us!