Seems ironic that since Edison invented the thing over 100 years ago, the universal symbol for a bright idea has been the light bulb, yet few really “see the light” in the first place—at least when it comes to motorcycles. I mean, we can all pretty much agree that you can’t have too much visibility in our “car eat bike” world, but the typical approach to brighter ideas for lighting on our sleds is actually pretty much dim and dimmer. It’s understandable, since the purveyors of such products don’t really go out of their way to shed light on the subject. The Motor Company is typical, in spite of their innocuous attempts to sell you $500 headlight upgrades based on a simplistic chart in the P&A catalog, but they are not alone, nor to blame, since they are in very good company among companies who keep us in the dark about lights. Actually, there are two categories that concern us here: 1) lights to be seen by; and 2) lights with which to see. Taillights, turn signals and running/marker lights fall into the first; headlights, spot/passing lights and auxiliary/fog lights into the second. Leaving bureaucratic regulations out of things, since they are conflicting and confusing worldwide, let’s just try to focus in on basic common sense, OK? Even though the factory is still curiously reluctant to switch from incandescent lamps to light emitting diodes (LEDs) for what I will henceforth refer to as “running” lights on its products, they are clearly the way to go in the future. Not necessarily because they are brighter, but for the three prime features they bring to the party, namely, low demand on the electrical system, cool operating temperatures and a nearly blow-proof long-lived nature.

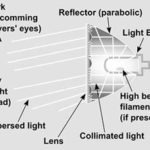

Our old friend the parabolic headlamp, as used on Harleys in 5 3/4″ and 7″ diameters since before most of us were born. The glass lens is cut or molded with facets to aim the light bounced off the smooth mirrored reflector into distinct high/low beam patterns. Still not a bad setup when used with halogen bulbs, but decidedly inferior (because of too much diffusion) in terms of useable light at about 27 percent.

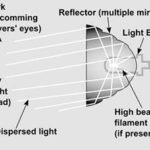

The thinking here is that optically neutral lenses, shedding light patterns from faceted reflector surfaces, are superior. Bounce light off the back and don’t diffuse it through the lens, and all else equal, the newer so-called “FF” lamp design offers useable light in the neighborhood of 45 percent, a near 90 percent improvement.

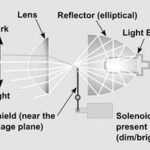

The ellipsoidal or DE type is useful for really small custom lights or fog/spot lamps, because it will put out quite a lot of light (38 percent useable) relative to its size, even if pinpoint penetration suffers. Unique in the use of a double reflector, “projection systems” like this are best for penetrating fog because of extremely sharp cutoffs. However, slight fuzziness and a small percentage of stray light is desirable for dipped beams so that traffic signs hanging above the roadway will also be visible.

Whether an upgrade (in available area) from a 5 3/4″ to a 7″ lamp, or straight swapping of a clear FF lamp for a cloudy parabolic (like this one on the right) makes for a really bright idea. Except…Whether an upgrade (in available area) from a 5 3/4″ to a 7″ lamp, or straight swapping of a clear FF lamp for a cloudy parabolic (like this one on the right) makes for a really bright idea. Except…

…for the additional decisions involved! Like, trying to determine in advance which of these two lamps (one with a reflector cone and one without) will actually do the best overall job.

Baggers (natch!) have the option of the “Full Monty” when it comes to lighting for nighttime cruising. Even though the slight gain in efficiency (roughly 52 percent useable light) doesn’t match the expense of this HID headlamp, those halogen passing lamps most likely make up for it. Thing is, I doubt that (high-speed) high-beam performance is anything like as good as an FF setup with about 130 watts to summon, when you flip the switch for warp speed in the dark.

Since mere laymen can’t tell until they try, why not hedge the bet? Since the light on the left in the last photo has something of a “DE” character to it (with that bulb cone), and the object of this swap is more light everywhere rather than just on low beam – add a stronger bulb like this PIAA. Then, go with the lamp that’ll let it all shine through! Losing the cap might even prevent any kind of dark hole in the center of the patterns… ya think?

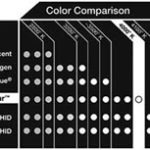

What with PIAA, Xenon, and more out there to choose from, bulb selection, like lamp choices, should hover around how close the illumination comes to white sunlight, how well (and how much) it projects forward, and how controlled the pattern is relative to your needs. That’s the simplest way out of the dark ages and into a brighter future.

Our old friend the parabolic headlamp, as used on Harleys in 5 3/4″ and 7″ diameters since before most of us were born. The glass lens is cut or molded with facets to aim the light bounced off the smooth mirrored reflector into distinct high/low beam patterns. Still not a bad setup when used with halogen bulbs, but decidedly inferior (because of too much diffusion) in terms of useable light at about 27 percent.

The thinking here is that optically neutral lenses, shedding light patterns from faceted reflector surfaces, are superior. Bounce light off the back and don’t diffuse it through the lens, and all else equal, the newer so-called “FF” lamp design offers useable light in the neighborhood of 45 percent, a near 90 percent improvement.

The ellipsoidal or DE type is useful for really small custom lights or fog/spot lamps, because it will put out quite a lot of light (38 percent useable) relative to its size, even if pinpoint penetration suffers. Unique in the use of a double reflector, “projection systems” like this are best for penetrating fog because of extremely sharp cutoffs. However, slight fuzziness and a small percentage of stray light is desirable for dipped beams so that traffic signs hanging above the roadway will also be visible.

Whether an upgrade (in available area) from a 5 3/4″ to a 7″ lamp, or straight swapping of a clear FF lamp for a cloudy parabolic (like this one on the right) makes for a really bright idea. Except…Whether an upgrade (in available area) from a 5 3/4″ to a 7″ lamp, or straight swapping of a clear FF lamp for a cloudy parabolic (like this one on the right) makes for a really bright idea. Except…

…for the additional decisions involved! Like, trying to determine in advance which of these two lamps (one with a reflector cone and one without) will actually do the best overall job.

Baggers (natch!) have the option of the “Full Monty” when it comes to lighting for nighttime cruising. Even though the slight gain in efficiency (roughly 52 percent useable light) doesn’t match the expense of this HID headlamp, those halogen passing lamps most likely make up for it. Thing is, I doubt that (high-speed) high-beam performance is anything like as good as an FF setup with about 130 watts to summon, when you flip the switch for warp speed in the dark.

Since mere laymen can’t tell until they try, why not hedge the bet? Since the light on the left in the last photo has something of a “DE” character to it (with that bulb cone), and the object of this swap is more light everywhere rather than just on low beam – add a stronger bulb like this PIAA. Then, go with the lamp that’ll let it all shine through! Losing the cap might even prevent any kind of dark hole in the center of the patterns… ya think?

What with PIAA, Xenon, and more out there to choose from, bulb selection, like lamp choices, should hover around how close the illumination comes to white sunlight, how well (and how much) it projects forward, and how controlled the pattern is relative to your needs. That’s the simplest way out of the dark ages and into a brighter future.

I can’t speak for everyone, but damn it’s nice not to have to worry whether the ass-wipe SUV tailgating you in the rain can see your brake light when it’s time—and in time! (I always worried about that with regular taillight bulbs.) Besides, let’s be honest, a ton of the motivation to convert from standard to LED running lights has to do with “bling” more than anything. All the same, it’s better stuff for running lights, and comforting to know that once swapped, LED lamps won’t burn, blow or melt precious pieces elsewhere, be they alternators or saddlebags or anything that has to live with the new lighting. Fact is, in the next few years, LED technology will probably encroach on lights in the second category of our discussion. But for now…

Lights by which to see are the most problematic, if for no other reason than the profusion of misinformation and fable about what works best. On the other hand, there’s this lack of a “standard” by which we can make an intelligent choice and even more appalling, our basically uninformed and informal attitude about it all. Truth be told, once the sun sets it all results in most of us simply riding (at reduced speeds) behind what the factory provides, and our awareness levels amount to the lamp either working or not working. Hell, most of us even use the terms “headlight” and “headlamp” interchangeably, when they are not even the same thing! Technically, any “lamp” is merely the device that provides the light. For those who wish to ride faster after dark the question becomes: How much light? The answer should include such details as what color, what strength, what kind, how well aimed and so on. So, here we go… on the path to en“light”enment.

What color? We’ve all seen older cars and bikes with headlamps that appear to throw “yellow” light as compared to new stuff. These old incandescent lamps, be they six-volt or 12, were fine for decades (since they beat the hell out of acetylene), until you saw what appeared to be much brighter, whiter light from halogen car lamps, starting in the late ’70s. Lately, as you blast up and down the highways and byways, used to white lights as you are by now, you’ve prob’ly seen (and how could you not?) screamin’ bright blue-tint lights on late-model crotch racers comin’ at you. (Yep! Thought so!)

Well, there are a couple of points I’d like to make. Blue lights are much more in the “to be seen by” class than they are in the “to see by” class. One of the attributes of light that physicists measure is its color temperature, which is expressed in Kelvins. Average daylight runs around 5500K. Lower numbers are closer to the red end of the spectrum, and higher numbers move toward blue. The best light for humans to see by is closest to the color temperature of sunlight. Neither archaic yellow light from yore nor the trendy “new” blue are as good. And, for the record, as we shall soon see, regardless of the color of the light, headlights can benefit from the sheer power of the light, just not necessarily in the ways you might expect.

What strength? I doubt there’s anyone out there who’s tried swapping, for example, the standard 55/60 watt H-4 bulb in his or her headlamp for something more powerful and not (literally) seen the benefit. Since cars sport at least two bulbs with 60 watts or more available on high beam, getting as close to a total of 120 watts of power to the lights as you can get seems like a logical “equalizer” for those who want the same visibility advantages for their scoot. Indeed, much brighter light can be had from, say, an 80/100 watt conversion—more is better, as we all know.

Alas, the downsides are nearly off-setting, in terms of wear and tear on the charging system, socket-melting levels of heat, and drains on the only source of DC voltage available to power that bulb—the battery! One ray of hope for “hot” bulb fans might be the PIAA H-4 bulbs, marketed as “X-treme White Plus,” “Star White” and “Super Plasma GT-X.” These are certainly of high quality and are bright enough, with Kelvin color ratings of 3,800–5,000, but the neat deal is they claim to offer “power” in the range of 100–135 watts (depending on bulb choice among the three), yet only draw power in the same 55–60 watt range as stockers!

There are, however, a couple of other oft-overlooked considerations: An increase in wattage alone does not equal the identical percentage increase in available light. The effectiveness of the lamp effects the efficiency of the light, regardless of the potency of the bulb. Put another way, whether it’s rated in watts, lumens or candlepower, you’ll get more useable light out of whatever source you choose by installing it in a lamp of superior design (and cleanliness).

What kind? Early headlamp designs amounted to a light source stuck in between a mirror and a lens. Somewhere along the way someone had the bright idea of cutting facets into the lens to aim the light more effectively on the road ahead. For about the last 10 years or so, the notion has been inverted to leave the lens alone and put all the refractive surfaces on the reflector! So far, that idea has stuck, so today the design parameters are mostly around precise patterns and, interestingly, the light source.

As good as halogen technology has gotten over the 30 years it’s been with us, it’s slowly losing the fight for light against so-called High Intensity Discharge (HID) designs. The leap forward with HID lighting revolves around the fact that it doesn’t involve a traditional filament at all. HID lighting systems use a special quartz bulb that contains no filament and is filled with xenon gas and a small amount of mercury and other metal salts. Inside the bulb are two electrodes separated by a small gap (about 4mm or 3/16 inch). When high-voltage current is applied to the electrodes, it excites the gases inside the bulb and forms an electrical arc between the electrodes. The hot ionized gas produces a plasma discharge that generates an extremely intense, bluish-white light.

It seems to me, Edison (and the acetylene brigade) would love it! Especially since HID could add a whole new dimension to the idea of a “blown” bulb, because once ignited, the pressure inside an HID bulb builds to over 30 atmospheres due to heat (up to 1,500 degrees!). So (har har!), there’s actually the danger of potential explosions! Another heads-up about HID “ignition”: The normal 12 volts DC from the vehicle’s electrical system is stepped up and controlled by an igniter module and inverter (ballast), which also converts the voltage to AC (alternating current) necessary to ignite the HID headlamps. It typically takes up to 25,000 volts to start the xenon bulb, but only about 80–90 volts to keep it operating once the initial arc has formed. When HID headlamps are first turned on, the light appears more bluish but quickly brightens as the bulbs warm up. Because there is no brittle filament inside a Xenon HID bulb to break or burn out, the headlamps typically last up to three times longer than halogen headlamps (3,000 hours versus 1,000 hours of continuous operation).

Sounds peachy, and I know you are just dying to go out and convert, right? Well hold on! Because they are arcs rather than tubular bulbs, HID lamps use totally different “optics.” So, the most dangerous part of the attempt to “retrofit” Xenon HID headlamps is that sometimes you “see” a deceptive improvement in the performance because of the much higher level of foreground lighting (on the road immediately in front of the scooter). The result is the low-beam illusion that you can see better than you actually can, and that’s not safe. Not only is foreground lighting of decidedly secondary importance when traveling much above 30 mph, but having a very strong pool of light up close causes your pupils to close down, worsening your distance vision, all the while giving you this false sense of security. Plus, the beam patterns produced by a conversion virtually always give less distance light, and often alarming holes in the pattern, just where there should be plenty of illumination. HID lamps are an animal unto themselves, so radically different that they must be designed from the start as HID applications for OEM systems, or they can be a dangerous waste of money and effort. (Most HID setups for motorcycles still use good ol’ halogen bulbs for high beam anyway!)

How aimed? It’s tricky to judge headlamp beam performance without a lot of knowledge, a lot of training and a lot of special equipment, because subjective perceptions are very misleading. I’d be remiss if I told you there was some foolproof way to pick the best reflector design (or coating), or the bulb that will make for the best compromise between intensity, draw or longevity for that matter, yet a couple of things are crystal clear. Halogen lights give off gasses that sooner or later cloud the lens and reflector. By the time you can see it forming on the inside of your headlamp, it’s likely to have cut the efficiency of your light by as much as 20 percent! Cleaning the parts of the lamp thus affected is a task that should be a part of your routine maintenance program. Simply remove the lamp, take the bulb out of the back and swipe around inside with a soft, dry brush (either of the painting or makeup applying variety) until things are crystal clear again. This little routine alone can gain you as much night visibility as any number of so- called upgrades.

Lastly, beware of swapping out your motorcycle headlamp for one designed for a car; they are distinctly different in the way the beam patterns are cut. Come to it, there are too many subtleties in reflector faceting among legitimate motorcycle applications to go into here, beyond mentioning the obvious: Namely, that the most satisfactory pattern(s) on low and high beams are likely to be different for those who cruise on well-lit city streets, versus those who boogie in the boonies. In the end, you can only focus on what works best for your riding style and stay clear of any hyperbole in parabolic lighting. Once you get it right, you’ll lighten up, and feel truly safe and comfortable in the dark.