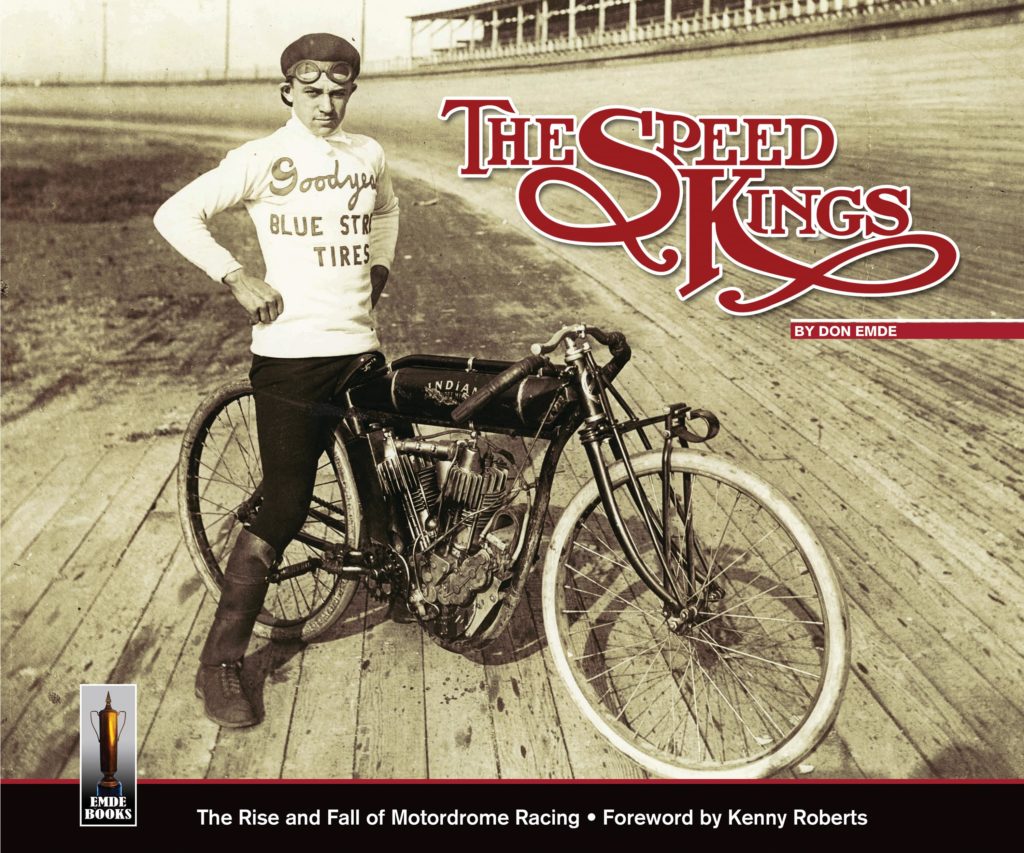

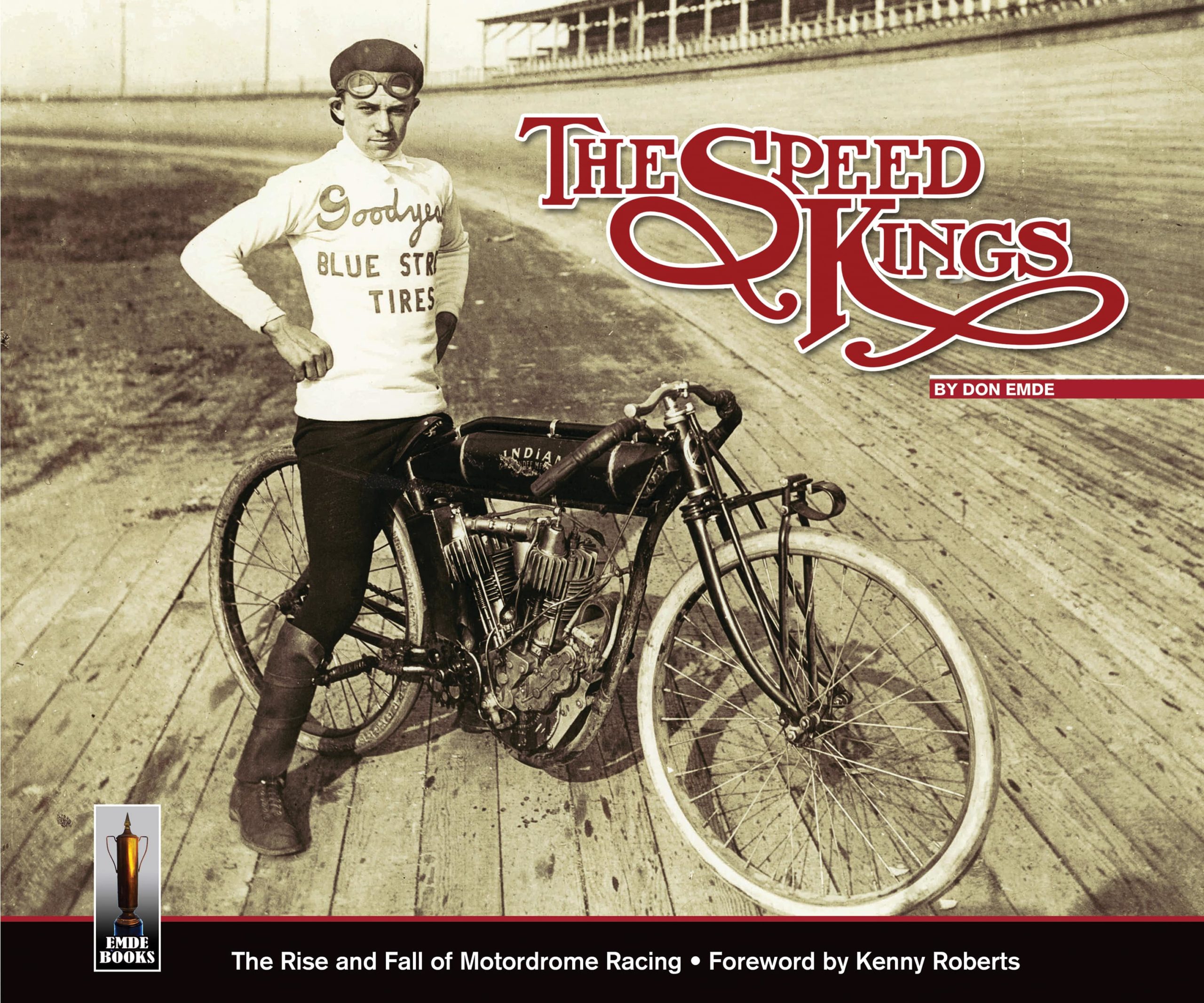

The Speed Kings is a fascinating and entertaining read, a book that chronicles a load of motorcycle-industry development alongside the competition aspect

It’s a book you’ll refer to again and again – and treasure – as long as you’re around. We spoke to Emde about the process of doing the book a few weeks back, and here’s what he had to say:

Thunder Press: You’re a longtime racer, and you’ve been around the block. Does it amaze you that these guys actually did this stuff?

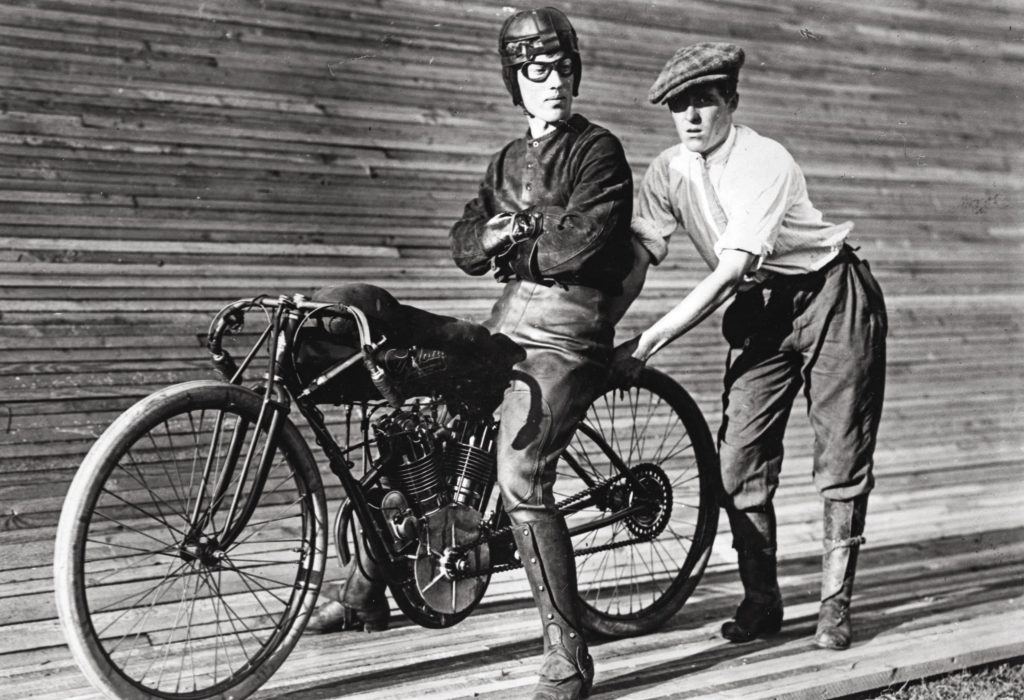

Don Emde: I wasn’t amazed that there was racing going on in the first decade of the 20th century. I’d known that for years. It was the speeds that surprised me. I’ve been around a lot of early-day motorcycles, even ridden a few, and think of them achieving 40, maybe 50 miles per hour, tops. But these guys were running so much faster. I would never have guessed before digging into this that these motorcycles were running 80, even 90 mph by 1912, and over a hundred by the end of the story. And on the high-banked, 360-degree motordromes, the top speeds were the average speeds!

I also got hooked on the format of the events, not unlike how Speedway racing works today. They were mostly short-distance races, and spectators saw many events during a race program. The races all began with rolling starts and some would only last 60-90 seconds. Races longer than five minutes were rare. This was one of the things that made motordrome racing so popular in the big cities. People could hop on the downtown rail for a ride to the track for an evening show and the event would run about two hours.

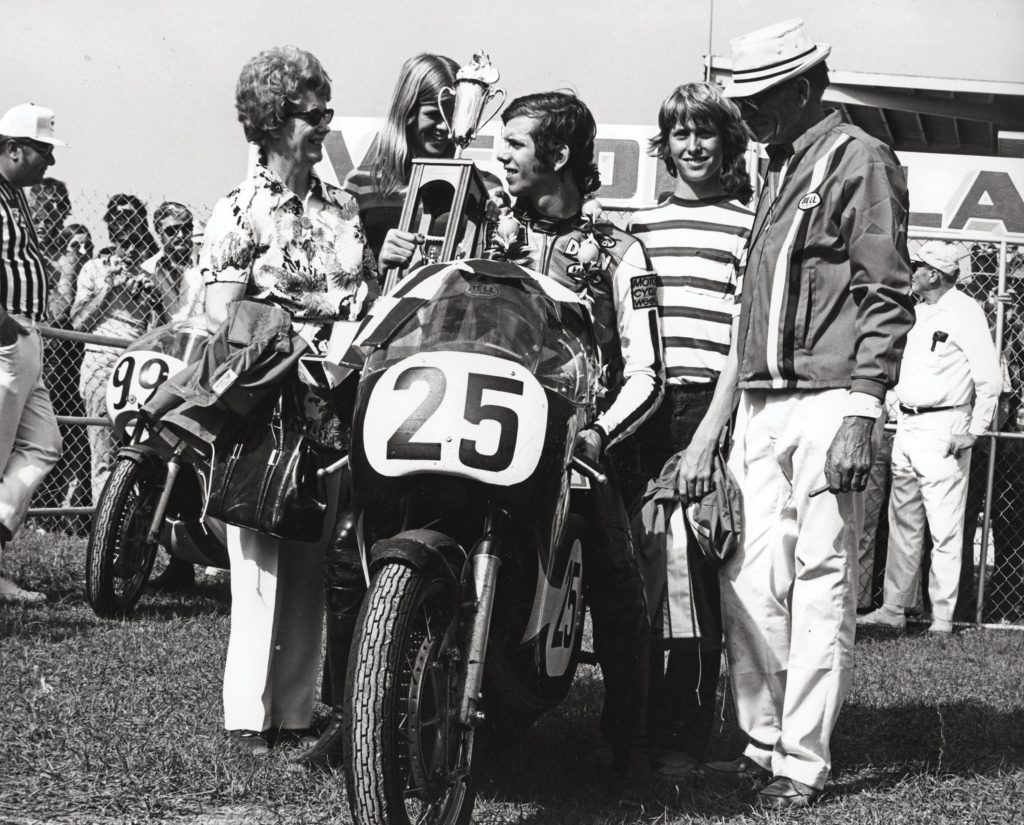

TP: When do you first remember reading about and understanding board track racing? Did your dad [Daytona winner Floyd Emde – Ed.] have input here? Or was it organic for you?

DE: Having been around motorcycle racing my whole life, and collecting the many magazines and books I have, I think I had one big snapshot in my brain of everything with the low-slung-handlebar bikes that are universally called ‘boardtrackers.’ Back then it was like all one thing…which of course it wasn’t, any more than thinking of Sandy Koufax pitching to Babe Ruth. You have to break things down decade-by-decade, even year-to-year, to understand how things evolved.

My earliest memories growing up in National City (San Diego County) was when my parents had a Harley-Davidson dealership and there were a couple of a rooms at their shop just jammed with old bikes and parts. There was an empty lot behind our backyard where they kept 15 to 20 old bikes, and when I was little I spent a lot of time sitting on them, sometimes with neighbor buddies, and we’d act like we were racing each other. At the shop my dad had a little lounge area with a coffee pot and an old-style soda machine. He had some of his racing trophies in a glass case with cork board above it that had lots of 8×10 glossies tacked on it.

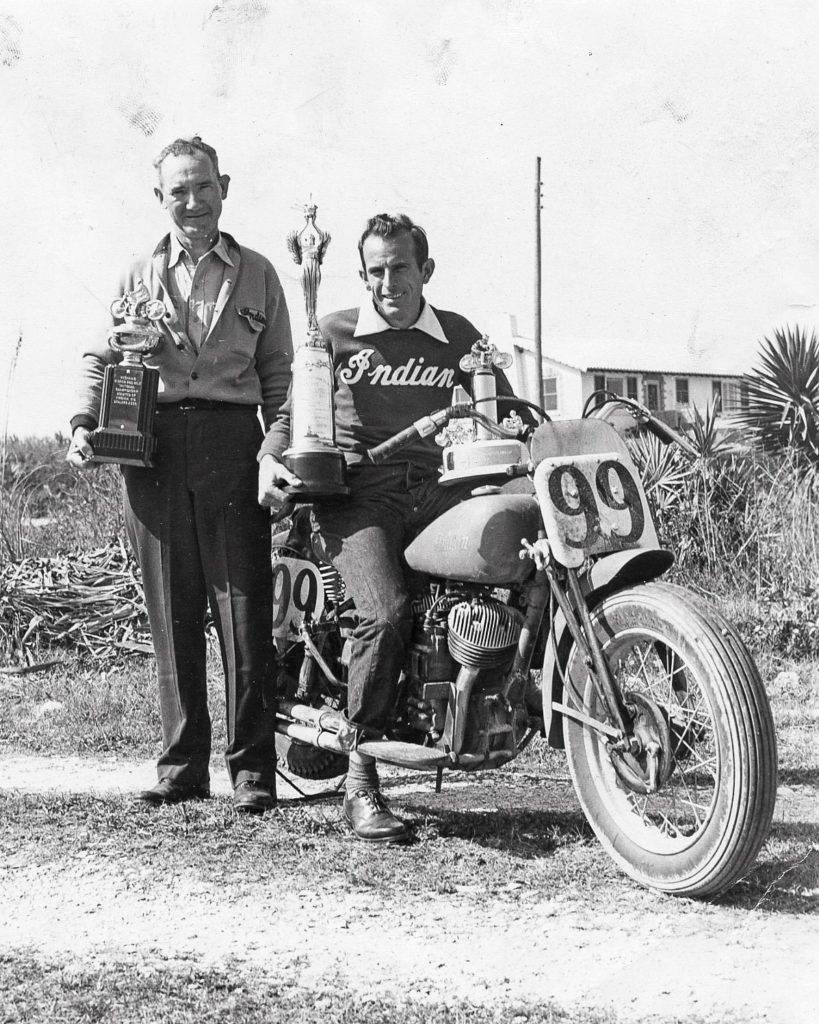

As I grew up my dad would sometimes pull out boxes of old motorcycling photos. Many were of his racing and some showed early day ‘boardtrack’-style bikes. My parents had been in the industry a long time, since 1948, when west coast Indian distributor Hap Alzina convinced my dad to use his $2,000 winnings from Daytona to become an Indian dealer. That only lasted one year, though, as Indian was going belly up and had many problems.

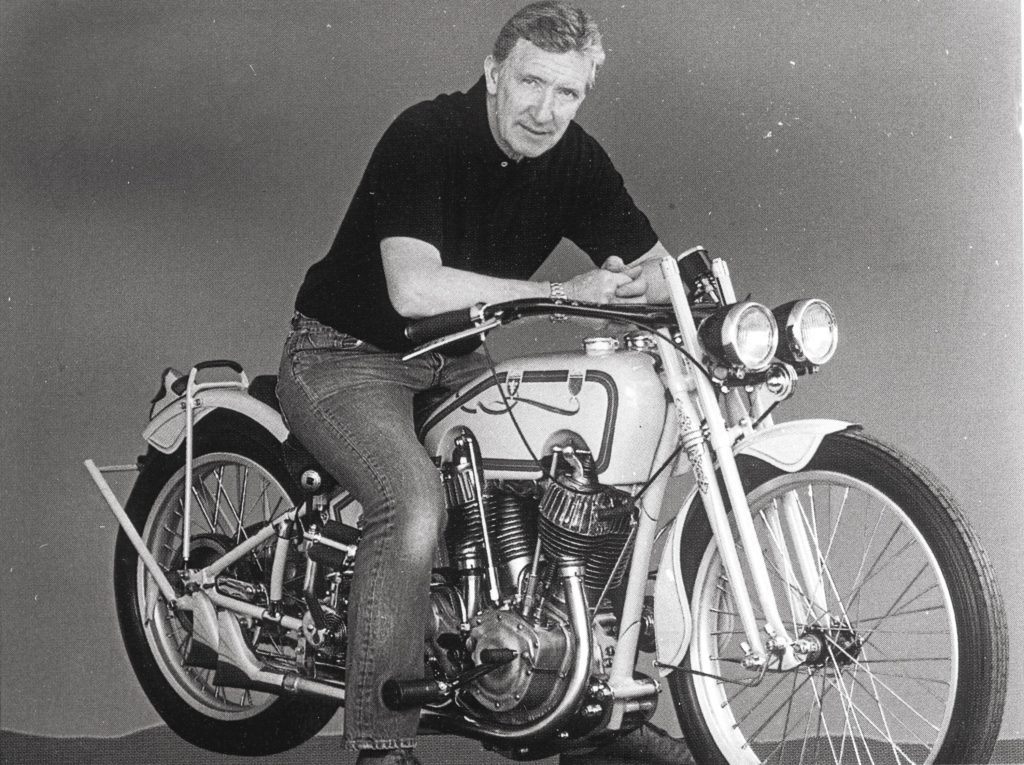

Luckily, Dad had connections with Harley-Davidson, too, as he actually raced Harleys more than Indians, although he is best known for winning Daytona on an Indian. He became a Harley dealer in March of ’49 when the local Harley-Davidson rep walked into Dad’s shop with Arthur Davidson, one of the four original founders of The Motor Company, and asked him to take on a dealership. They eventually sold all three of their stores in 1980 and retired, though he still had a lot of old bikes, including one I didn’t recall because it was not a rolling motorcycle, just parts. He called it a ‘Peashooter’ and wanted to know if I’d want it? (Of course I said yes.)

He told me a little about Harley Peashooters, saying that Joe Petrali made them famous in the 1920s and ’30s. (One year Petrali won all 13 FAM nationals on one.) Dad had gotten the Peashooter as a gift from Milwaukee Harley dealer Bill Knuth when he won the 1947 Milwaukee 10-Mile National. Knuth had given Floyd some workspace at his shop the week of the race and at one point noticed that Floyd was checking out this old race bike and some motors Knuth had gotten from the factory many years before. After Floyd won the race on Sunday on his Harley WR, Knuth gave him the Peashooter, engines and parts when Dad went to the store Monday to retrieve his tools.

TP: When and how did the original idea for book come about? You’ve said you have a massive magazine collection…and that is was a long and arduous project. Tell us about that.

DE: When my parents wrapped up their business, my dad passed on to me not only the Peashooter but also all of his photos and many old magazines. All that got me started with an interest in the old bikes. About this time Stephen Wright also published the first edition of American Racer, his large-format photo essay that he self-published about the first 40 years of motorcycling in the U.S. And Harry Sucher wrote his two in-depth histories: “Harley-Davidson. The Milwaukee Marvel” and “Indian. The Iron Redskin.”

I was suddenly saturated with early-day historical details and was soon hungry to obtain any or all information about those early days. That’s when I started to build a magazine collection in earnest. I have complete sets of the magazines we all know, Cycle, Cycle World, Motorcyclist and American Motorcyclist, but I also have many copies of early-day magazines from the teens, some of which I bought full collections of on eBay. I’ve lost track of how much I spent building the collection, but as can be seen in the Bibliography of The Speed Kings, I used over 1,000 magazines in the research. What I did was go through all my magazines to see if there was any content about boardtrack racing. When I found issues that did, I brought them home and scanned the pages, ending up with over 6,000 pages of material, saved by year and date, which then gave me a chronologically organized research library.

TP: Any other collections you’ve amassed?

DE: Through the years I started adding more photos to my collection. I had all my dad’s photos, and ones I had bought from photographers when I was racing, and then I acquired noted photographer Dave Friedman’s collection. In the early 1990s I started a magazine called Motorcycle Collector, and along the way, the great-grandson of pioneer motorcyclist, AF Van Order, contacted me and let me know he had the negatives of a large collection “Van” had amassed in the early days when he used to sell photo prints. I was given permission to use the whole collection as I wished.

Through the years I have been able to acquire some loose period photography, as well as scrapbooks of notable motorcycle racers, and some images from the scrapbooks were used in the book. I was also able to license the use of images from the scrapbooks of Indian founders Oscar Hedstrom and George Hendee. That involved a trip to Massachusetts to go through their scrapbooks.

A big break also came when I learned that the lone surviving member of the Stephen Wright family was looking to find a good home for the motorcycle history library of my old friend, a transplanted Brit that had become a top-shelf restorer of early-day motorcycles, and who counted Steve McQueen among his selective list of clients. While helping McQueen with an acquisition, he came across a well-preserved treasure trove of photos and other historic motorcycle history material that was once the collection of pioneer motorcyclist Paul “Dare Devil” Derkum. The Derkum collection represented the bulk of content for a book titled “American Racer 1900-1940” that Wright wrote and produced in 1979. Other books followed, but he remains best known for American Racer.

I traveled to central California and made the deal to acquire his many early-day photos, race programs, newspapers and other significant history material. Much of it was used in the production of The Speed Kings. Paul Derkum’s early-day motorcycling is featured in The Speed Kings, as well as photos, newspapers and other items used through the book.

TP: How did this whole project come together?

DE: For some time I had thought a book about boardtrack racing would be cool to do, but I got involved in a Cannon Ball project in 2012 that ate up a lot of time. I got going again on it in 2017 when I started going thru my collection and scanning magazine pages. That’s all I did for about a year. Production got going in 2018 and then it was full speed ahead.

That’s also when my worlds began to collide time-wise…I still had my magazine business to run. So my body clock changed and I found myself getting up around 3:00 a.m. to do my writing. I would often accidently wake my wife up as I got up and on my way out of the dark bedroom would often hear her ask, “Are the guys calling you to go tell their story?” And I would answer “yup.” She was convinced I had opened up a channel to hear these guys telling me to get busy on the book every morning. I still wake up early every day.

TP: What are the most amazing things you learned while doing this book?

DE: I don’t want to give too much away, but there are a few things, such as how much bicycle velodrome racing impacted the creation of motordrome racing. That might seem obvious since both used board surfaces, but it was so closely aligned that it left a gray area for the question of where was the first motorcycle boardtrack race held.

I found it fascinating to learn how in the late 1800s there was a major competition to determine if motor vehicles would be powered by gasoline, electricity or steam. One of my favorite stories in the book that I never expected to write when I started is titled: “The Summer of Steam.”

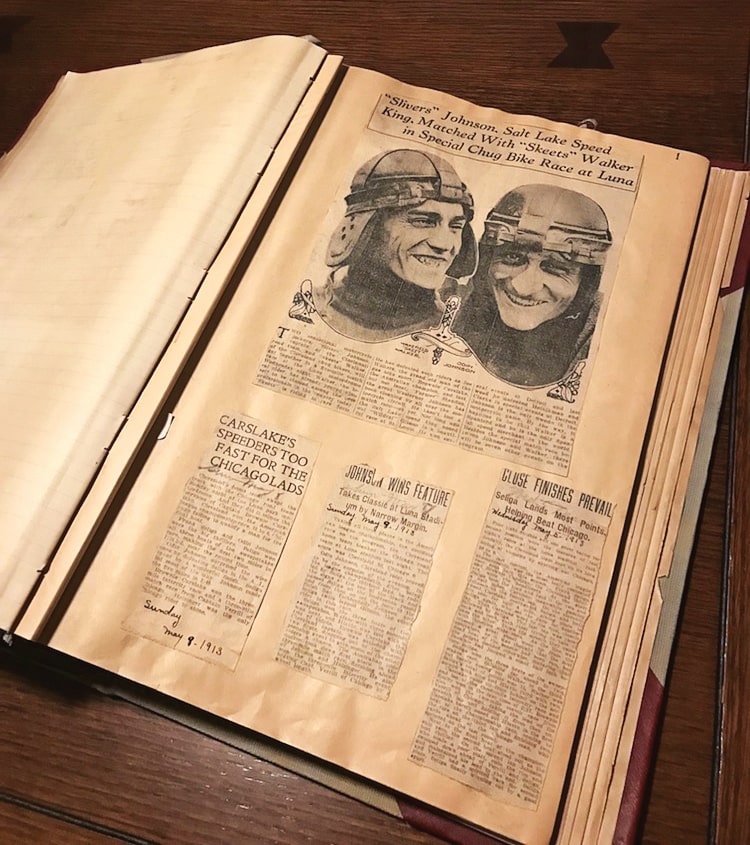

In the book, I wrote about a racer named Odin Johnson, who was involved in that terrible accident in Ludlow, Kentucky at the Lagoon Motordrome, where so many folks got burned. I didn’t have a photo of him, so I had noted motorsports artist Hector Cademartori do an illustration of him from a blurry image taken from the internet. He did a great job, and I was all set. Then, a month or two later, I was contacted by a guy who has helped me through the years with historic materials, who asked if I’d be interested in an old scrapbook of a racer named Odin Johnson. Wow! I of course said yes, worked out a price to buy it, and in about a week I was the proud owner of a scrapbook that Johnson’s wife had made way back in early 1900s. Not only did it contain some great photos of her husband, but also many others he raced with. It was such a great find that we went back and rearranged a couple of chapters to include the new images. My wife Tracy was already commenting that I was hearing voices from the subjects of my stories, but we were pretty amazed that now one of them sent down his scrapbook!

TP: What’s the difference between motordrome and boardtrack racing? They are a little different, eh?

DE: The reason I used primarily ‘motordrome’ instead of ‘boardtrack’ was to differentiate between the first era of racing (primarily pre-WWI) on the little quarter-, third- and half-mile circular tracks vs. the post-WWI era on what were then called the Auto Speedways. Those were the longer, one-plus-mile tracks like Beverly Hills, Altoona and others. Both types were on board tracks.

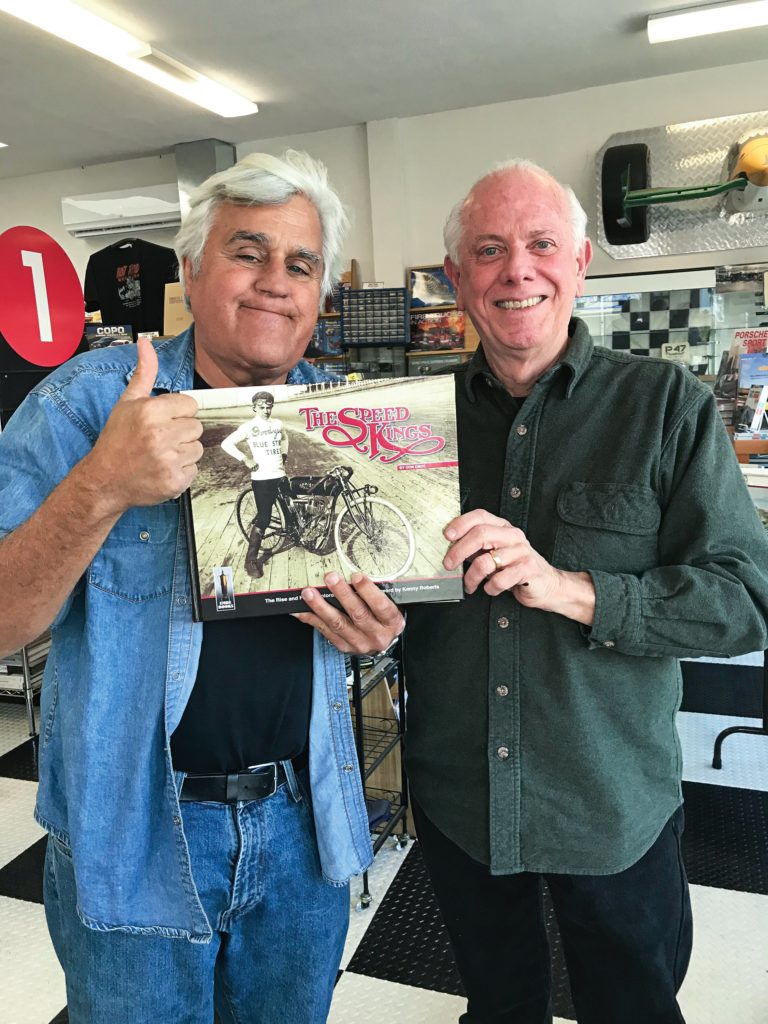

TP: Tell us about the Dean Batchelor award you got from the Motor Press Guild for Best Book of 2019. First time ever a motorcycle title won that award, yes?

DE: Batchelor was one of Joe Parkhurst’s early staffers and supporters who went on to have a long and successful career with Road and Track and other publications, plus authoring The American Hot Rod and other books. When The Speed Kings was finally printed I sent some copies out to contributors to the book, and one went to Hector Cademartori for the great drawing he made. When he got his copy he contacted me and let me know the judging was going to be held soon for the Dean Batchelor awards and that he had shown his copy to people at the Motor Press Guild. Next thing I knew I had the book entered and it turned out that it won!

TP: Tell us about book availability, pricing, etc.

DE: We primarily sell direct through my website: EmdeBooks.com. Additionally, Burbank Autobooks and a few motorcycle museums are carrying it also, including The Barber Museum (Birmingham, AL), Wheels Through Time Museum (Maggie Valley, NC), The National Motorcycle Museum (Anamosa, IA), Motorcyclepedia Museum (Newburgh, NY).

The book by itself sells for $75, plus $10 shipping (and tax in California). These orders are shipped from our printer in Kansas City. (Yes, not offshore!) We also offer the book in a bonus package with reprints of three historic items shown in the book. Since those copies are shipped from my office, I also sign those copies for buyers. My email is: don@emdebooks.com.

We normally take international orders, but have turned off that option temporarily during the Covid-19 pandemic. The dramatic reduction in airline flights had already slowed overseas shipment to 4-6 weeks, but the EU shutdown of travelers from the U.S. to Europe has pretty well brought that to a halt. If someone from Australia, New Zealand, Japan, etc. wanted to place an order, they could email me and we could process it thru PayPal. Shipping internationally is terribly expensive ($75 for postage, plus the cost of the book), but we seem to have had good demand anyway.

[…] Part 2 of Speed Kings features and exclusive interview with author Don Emde. Click here. […]