Game changer

Reinventing custom cool—and competence

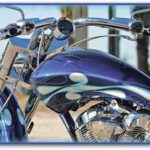

Daytona Beach—The Wolf’s swirling blue and white paint scheme looking like a whitecap breaking over the entire length of the machine, we’re cruising in sixth gear at 70 mph, taching a leisurely 2700 rpm in an eerie operational calm, and the sensation is one of surfing the Interstate on a two-wheeled tsunami. There’s no better way to put it. The mirrors are still and engine noise virtually undetectable; it’s just onrushing wind and the receding thrum of the exhaust. Eerie. And then an impulsive twist on the throttle and the Wolf lunges forward without a hint of low-rev hesitation, topping 90 in an exhilarating moment. A huff and a puff and we’re blowing the doors off everything on the road.

And it just gets better from there. Vectoring off the superslab and up the sweep of the exit ramp, my instincts—instincts honed by years of test riding radical custom machinery with big motors and big tires and big radical chassis configurations—go on full alert, and my body tenses to ride out whatever unfamiliar handling idiosyncrasies this big bastard is fixing to deliver. None come. The Wolf leans into the curve gracefully—almost instinctively—and holds the line, stable as a tractor.

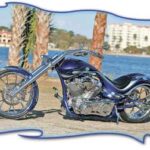

This model is a game changer on a number of fronts, defying comparison with anything else on the market, both in looks and functional outfitting. That’s certainly the case with tire size, where the Wolf has broken with fat-rubber orthodoxy utterly, mounting a 220 on the rear and taking a gamble of sorts on acceptance in the contemporary custom scene, represented here by the boulevard beauty pageant of Main Street. This is where fat rubber has ruled for a number of years, as builders have put ever greater slugs of meat on the pavement and succeeded in defining custom cool as a function of footprint. When that swelling reached its impractically practical extreme at 330 mm, custom component suppliers changed course and went up instead of sideways, making really tall tires for both the front and rear. And while that innovation got limited traction in the broader custom market, it was embraced by some prominent builders, among them Big Dog, which put a 23-inch wheel on the front of their 2008 Pitbull model, and a 20-incher in back. Even there, though, the rear rubber remained a stout 280 mm, and well within fat rubber orthodoxy.

Considering Big Dog’s leading role in popularizing fat tires, it does come as something of a shocker that the Wolf runs on that 220/50-20—the skinniest rear tire to come out of Wichita in six years—and, again, it’s something of a gamble, but only in a fashion sense. As a functional consideration, that choice was made in anticipation of turning the Wolf to bagger duty, with the fitment of suitable hard bags being facilitated by a narrower rear section. (That’s a role the Wolf has yet to fulfill, and won’t fulfill until later this summer when development of the bags is complete.)

Likewise, the rubber downsizing was no gamble from a handling standpoint for very obvious reasons, and judging by audience response wherever the Wolf is parked around Daytona Beach, the fashion gamble has paid off—or at least it hasn’t hurt. It’s hard to say to what extent the rubber even matters to the many admirers, who—like myself—are awed by the overall styling package, and by the truly unorthodox and utterly arresting X-Wedge motor.

The X-Wedge edge

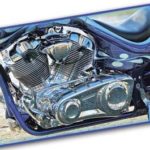

It’s impossible to understate the degree to which the 121-inch S&S X-Wedge defines the appearance, personality and performance of the Wolf, and for that reason a brief refresher course on the motor is in order. As we recall, the X-Wedge debuted in 2007 and represented the most ambitious design undertaking in S&S Cycle’s 50 years of V-twin engineering. Designed to take the classic concept of the big-inch, air-cooled, pushrod-actuated V-twin engine into a future of increasingly stringent emissions standards, the X-Wedge started with a clean sheet and brought a host of significant innovations to the form, starting, most apparently, with round cylinder barrels, 56 degrees of cylinder separation, and parallel pushrod tubes.

The round barrels bring two major advantages to the large-displacement platform: they permit a consistency of cooling fin size and placement that results in a reduction of power-robbing heat distortion of the liners, and they also permit the use of a five-bolt pattern at the bases rather than the conventional four. That, in turn, provides the strength required to accommodate a bore size up to 4.375 inches, and a corresponding displacement of a whopping 139 inches.

The 56-degree angle of the jugs lowers the inherent vibrational properties of the traditional 45-degree V while also creating the space necessary for large pistons to operate without necessitating notching of the skirts for bottom clearance. It also creates the space required for additional cooling fins as well as for the unique and highly efficient cross pattern of flow from the port-injected intakes to the exhaust manifolds—hence the “X” in the name.

The “Wedge” refers to the shape of the combustion chamber. Where conventional V-twins have a hemispherical chamber with a valve on either side of the room, the X-Wedge uses a wedge-shaped cavity with the valves parallel and actuated by automotive-style rockers. The advantages of that arrangement are virtually dead-straight pushrod angles, and rock-steady rockers relieved of the flex and jitters of a long rocker arm shaft. It also allows for solid pushrods since whatever adjustments are required above and beyond the self-adjusting hydraulic lifters are made in the rockers themselves.

Then there’s those parallel pushrod tubes. They’re aligned that way with the intake pushrods converging at the cam chest because the X-Wedge uses three cams—a common intake cam and a separate cam for each exhaust train. Those three cams are driven by a super-quiet, idler-tensioned serpentine belt rather than the chains or gears typically utilized in multi-cam V-twin configurations. And what’s more, the belt runs inside a dry chamber, making maintenance a faster and less oily proposition, when it’s required at all. The service interval on the Wolf is set by Big Dog at 30,000 miles. Replacement can be performed in about an hour total, and it’s worth noting that in the unlikely event that the belt is installed out of time or breaks outright in operation, the X-Wedge is what’s described as a “free spinning” motor, meaning the pistons and valves can’t smack into each other with costly consequences.

The upshot of the motor’s many innovations is that not only is the X-Wedge emissions compliant at least through 2010, it is a simpler, more efficient V-twin design that uses interchangeable components and fasteners to such an extent that there are actually 30 percent fewer parts and 44 percent fewer part numbers than on the current S&S 117 inch Evo-derived motor. It also emits appreciably less mechanical clatter and 21 percent less vibration.

The Wichita touch

It’s worth noting historically that, in a very real sense, the X-Wedge was made for the Wolf, and vice-versa. S&S Cycle was quick to acknowledge the pivotal role Big Dog played in creating the X-Wedge, as then-President Brett Smith of S&S told us in 2007, “Their desire for a specific type of motor really helped drive this project faster than it might have otherwise gone. They’re the company that will benefit most immediately from what the X-Wedge offers going forward.” And as a sort of thank you for the company’s involvement, the 121-inch version of the motor is proprietary to Big Dog. That configuration, with its equal 4.25-inch bore and stroke, also serves to lessen vibration, producing less than a stroked motor of similar displacement. It also produces an astounding 130 horsepower.

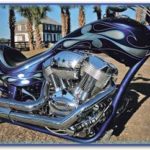

While all of the foregoing technical attributes of the X-Wedge are well and good from an operational standpoint, the X-Wedge’s somewhat blunt, stocky and utilitarian looks were less than prepossessing—at least when viewed in isolation on an engine stand at its unveiling. It was difficult to envision how the technologically brilliant motor could be put into production-model use and begin to compete in the looks department with the familiar Milwaukee-style V-twin.

That was a challenge for the Big Dog designers, and they responded by taking the duckling and producing a swan. Some of that transformation came naturally. By happy coincidence, the stock BDM air cleaner, in use for a number of years, looks like it was fashioned specifically for X-Wedge use, its contours complementing those of the motor perfectly. Likewise, the Baker/BDM Balanced Drive primary and BDM coil cover—both long-running staples of the breed—match up pleasingly with the motor’s left side where the round barrels are most prominent.

That part was easy. The components came right off the shelf, but Big Dog was just getting started. They then designed a new chassis with an arced single downtube and long swept swingarm and dressed it out with complete bodywork, and they combine to showcase the motor, playing off of every angle and radius to glorious effect. It’s a study in proportion and integration, and appears more the work of a calligrapher’s brush than a CADCAM cursor. Visually, the design flows in a seamless sweep from end to end, harmonizing every element from the Perse front end to the swept handlebar, sunken saddle and elegant fender struts. The Wolf looks in motion standing still.

So perfectly proportioned and integrated is it, in fact, that you scarcely notice the Wolf’s jaw-dropping 9-foot 4-inch length.

Master of deception

Not only does the extreme length of the Wolf not register in the eye of the observer, it also doesn’t register in the ergonomics of the operator. That stretch is achieved with extensions of both the backbone and the swingarm such that the seat position is well-centered amidships, and the reach to the grips and pegs remarkably natural. Throw a leg over, and any perception of an outsize ride dissolves.

That geometry translates to a surprising ease of operation. Around town the Wolf is a nimble maneuverer—again defying appearances—and the only time you become aware of just how long the bike is comes when parking on the street; backing up to the curb and suddenly realizing the front tire’s still sticking out into traffic. A lot. Some angle of attack is called for, and, curbside, the Wolf takes up the equivalent space of a couple of lesser motorcycles. Forget parking on Main Street.

Equally deceptive is that wafer-thin suggestion of a saddle. It’s thicker than it appears, settling into a recess in the bodywork, and it provides a perch adequately padded for extended seat time. With a 4.5-gallon tank—roughly 3.5 to reserve—and a fuel economy we found to be in the 35–40 mile per gallon range, depending, gas stops on the Wolf occur within the comfort zone of the seat… Just.

Kansas homegrown

Pretty much everything about the Wolf is pure Big Dog, and as such the model represents the successful completion of the company’s years-long campaign to erase any vestige of the dreaded “clone” disparagement that has plagued the production-custom industry from its inception. Every major component of the Wolf is produced in-house, designed in-house and jobbed out locally, or provided by suppliers exclusively to Big Dog. Every manufacturing process from motor-building to polishing and paint to final assembly takes place at the company’s Wichita facilities.

And success is sweet. Drop-dead good looks, neck-snapping power, tamed vibration and handling prowess at all speeds; that about sums up the Wolf. But more significantly, you may have noticed that this entire review has been free of the usual qualifiers we so frequently invoke when assessing the merits of custom-styled machines; the qualifiers used to excuse overall performance deficiencies as understandable trade-offs for custom panache. They’re unnecessary with the Wolf. There’s no devil’s deal struck here between what works and what wows. The Wolf does both with equal effectiveness, and when our chief complaint about a bike is the inability to park it perpendicularly to the curb, you can reasonably conclude we’re mightily impressed. We’ll go you one further, too: At a base price of a heady $35,900, the Wolf is actually… gasp… a bargain.