The hundred-dollar holiday

Doing the Mono-econo boogie on a Buell

Three hundred miles from home and 7,800 feet above sea level, the tent’s pitched, the kitchen’s set up and I’m sitting on a canvas camp chair, cold Tecate in hand. The view down the Little Walker River valley is spectacular and the soundtrack consists of breezes through the quaking aspen, the occasional chirps of solitary vireoles darting about the foliage of an ancient Jeffries pine, and the soughing of Molybdenite Creek, a fast-flowing boulder and log-strewn Sierra trout stream 20 yards downslope. On the menu for supper is a starter of smoked oysters and marinated mushrooms followed by homemade wild boar chili. After supper I’ll light a fire; tight-grained well-seasoned aspen sawed to length lies stacked by the fire ring alongside some bomb-grade sagebrush and pine needles to set it ablaze at the strike of a match. On the evening’s entertainment program is the Perseid meteor shower.

This is as close to paradise as I’m ever likely to find myself. You gotta love these high-dollar adventure camp excursions where you ride in scenic wonder all day and arrive at a deluxe, fully-provisioned camp setup.

Only that’s not what this is. Little more than an hour ago I arrived at a deserted campsite in the Toyabe National Forest. Everything here came up with me. Everything, that is, except the firewood, and for that I’ve brought a hatchet and saw. And it all came up aboard a Buell.

This is exactly what the XB12XT Ulysses was designed for—getting away from it all while at the same time taking it all with you. Touted as a distance-touring sportbike, the new XT variation on the existing XB12X Ulysses theme emphasizes pavement prowess over the dual-sport pretensions of the original, and it does that with a combination of shortened suspension travel, a shortened operator-compassionate seat height, a stock complement of saddlebags and top box, and a set of Pirelli Diablo Strada long-wearing sport tires in place of the Pirelli supermoto-spec Scorpion Sync jobs of the X.

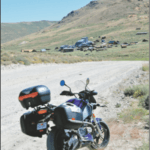

On paper, the XT is a Ulysses intended primarily for asphalt, but it’s impossible to behold the bike without seeing off-road possibilities and recalling the catchy “Adventure Sportbike” description that attended the introduction of the original X. And so it was with no reservations whatsoever that I charted a course for this caper that would include a number of miles of rugged dirt road.

The challenge

But what exactly is this caper? The objective is twofold, really, the first being to revisit my moto-camping roots that once accounted for virtually all of my two-wheeled travels, but which I’d neglected in recent years for various reasons, time constraints chief among them. The second objective is a timely one, methinks, in demonstrating just how cheaply a world-class adventure getaway can be had with a well-packed motorcycle and a bit of planning.

Towards that objective I set myself a budget of $100 which would be expected to cover my fuel for 750 miles, lodging expenses for two nights, food for three days, and any and all incidentals. To pull that off, all of my provisions would have to come with me. The XT would have to pack it all as well as all the gear I’d need for touring and camping in an isolated locale where the mercury can flirt with freezing at night and squirt up to triple digits in the daylight. Since I’d be camping in a primitive NFS campsite I’d have to pack my potable water in and any unburnable trash back out.

Pretty much any motorcycle can be outfitted for hauling a whole mess of camping gear provided you don’t mind going down the road looking like a downsized version of Jed Clampett’s flatbed. That’s how I usually roll, in fact, but the XT requires no such bastardizing, coming in stock trim with a positively daunting carrying capacity. Just how daunting? Here’s a list of what I packed aboard:

Two-man tent, winter sleeping bag, self-inflating air mattress, collapsible camp chair, two small Arctic Zone coolers, canteen, Sven saw, hatchet, full mess kit, espresso pot, two bottles of propane, camp stove, gas lantern, LED flashlight, dish and hand towels, two changes of clothes including thermal hoodie, Dopp kit, first-aid kit, CruzTools H1 tool kit, tire repair and inflation kit, S&W Model 60 with 10 rounds of snake-shot, camera and lenses, binoculars, notepad and pen, Audubon Field Guide to California, and a collapsible fishing rod and reel to give the trout something to laugh at.

And then there’s the food: Chili for two nights, a sleeve of soda crackers, two tins of smoked oysters, large jar of marinated mushrooms (supper), four hard-boiled eggs, four hot links, fresh-ground coffee, honey (breakfast), two packages of beef jerky, raft of string cheese, large bag of cashews (road lunch), ten cans of Tecate and a flask of snake-bite for emergencies real and imagined (general wellness).

With most of the food sourced from the local dollar store, and the chili being made from scratch with Personal Nurse-grown tomatoes and gunshot-pork donated by a neighbor, the total tab on the comestibles and libations is about $22. But I still have to pack it up and keep most of it cold—especially the beer—for the seven-hour run up to the mountains, and the trick to pulling that off without the messy hassle of ice is to freeze the chili and hot links overnight before departure and use those items to chill everything else. After a long hot day on the road, the chili thaws sufficiently to portion off the night’s meal, and the brewskis are nice and cool. Once ensconced in the NFS campground called Obsidian, I have a back-up beer cooler in the form of snowmelt-fed Molybdenite Creek.

Where do you want to go today?

Leaving Obsidian in the morning for a day of riding and sightseeing around Mono County is to ride back down three and a half miles of washboard dirt, dropping 800 feet in elevation over that short span. Riding the loaded XT up that road was a relatively leisurely exercise since riding up a dirt grade is always a more controlled proposition than riding down one, and I’d held it slow and steady to keep from shaking up the Tecates. Heading back down without that consideration means stepping up the pace and testing the limits of the Stradas on shifty footing. It’s tenuous going at times, but with a keen eye for trouble spots ahead and a readiness to stand on the pegs the XT descends smartly at a 30–35 mph clip which feels a hell of a lot faster. At the bottom of the road, it’s a simple matter of twisting the rear-suspension adjustment knob located just aft of your left leg to morph the machine from pack mule to quarter horse, and once out on the asphalt of Highway 395, the XT is in its element—agile and exhilarating and grin-inducing—and it’s nearly impossible to believe that this is the same mount that just schlepped an entire deluxe camp setup up a remote mountainside.

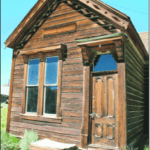

Twenty miles down Highway 395, past the biker-popular burg of Bridgeport, is the turn-off to the ghost town of Bodie. The first nine miles of the road in are good pavement with plenty of twists and turns to liven things up. And then the pavement ends, giving way to a final three-mile slog over a swath of battered washboard cinder dust and chunky gravel. It’s a grueling nuisance at times, but ultimately well worth it as the road rises to the rim of a mountain bowl and suddenly there in all its infamous glory lies the vestige of the meanest, most storied and ghostliest gold camp in all of the gold country.

Gold was discovered here in 1859, and by 1879, 10,000 souls called Bodie home. They called it a lot of other things too, none of them complimentary, as a combination of “the worst climate out-of-doors,” and daily, frequently lethal violence gave the place a reputation as an earthly hell, inspiring one young girl bound there to famously jot in her diary, “Goodbye, God. I’m going to Bodie.”

The mines played out and fires took their toll over time, and by 1940 what remained of Bodie was a ghost, but one whose desolate and barely accessible location kept human pillage and desecration to a minimum, and preserved the town in a sort of suspended animation. In 1962, the spooky remnants of Bodie came under the protection of California as a state historic park. Today the town is unrestored and only minimally maintained, like a biker’s teeth, in a state of “arrested decay.” Original furnishings, household goods, and even clothing remain where they were found, and layers of wallpaper sag in rags from the walls, and layers of flooring recede to reveal generations of remodeling of the simple cottages. Goods still stock store shelves, and unfinished coffins crowd the undertaker’s workshop. The place is truly arresting; the very embodiment of what the term “ghost town” has ever conjured in a kid’s mind. That sense is further heightened by the voyeuristic procedure used to view most of it: standing on tiptoe, hands shading eyes, peering through windows into dusty forlorn interiors—lifeless but palpably, spookily once lived in. Admission price: $3.

Highway 395 south to Mono Lake and the town of Lee Vining is motorcycling bliss; perfect pavement, broad banked sweepers, light traffic and scenic grandeur for miles. From atop Conway Summit, Mono Lake suddenly appears like a mirage on the alkaline plain below. And it doesn’t get any less surreal with the approach. Sea gulls swarm the lake, and fantastic sculptures of calcium carbonate called “tufa” dot the shoreline—created by upwelling of fresh water in the lake’s heavily saline waters, fully two and a half times as salty as seawater.

The lake’s pushing a million years old and sits atop an active volcanic zone, making this all a delight for geologically enthralled tourers like myself. It’s also an environmental success story, having nearly perished in the early ’80s as LA’s insatiable thirst drew down water levels and threatened to turn it into a dead sea. A land bridge even emerged connecting the shore to the lake’s Negit Island, a principal California gull rookery, and coyotes scrambled over to eat the birds. It’s taken a generation of activism and restorative efforts to arrest and reverse the damage.

You get a good eyeful of Mono Lake from Highway 395, but the real fun way to experience the lake and the adjacent volcanic landscape of the Mono Craters is to turn east on Highway 120 at the south end of the basin. This is one of the loneliest roads in the West. It’s truly a Road to Nowhere—unless you consider Tonapah somewhere—but it takes you first to the gravel access road to the South Tufa and to Navy Beach—once a top-secret weapons testing site during the Cold War where, under the guise of doing seismic research, mad scientists experimented with death rays and exploding seagulls. I guess. To this day we don’t know exactly what they were up to.

And then the road takes you to the dangedest stretch of asphalt whoop-de-dos you’ll ever encounter. Better known to locals and inveterate road-dogs as the Roller-Coaster Road, the pavement dips and rises in rapid sequence for miles, and you can get air there. As it leads on, you’re treated to dramatic views of the White Mountains—Nevada’s counterpoint to the High Sierras. But that’s as far towards Nowhere as we’re going today, and I reverse course for another ride on the roller-coaster, and then a stop in Lee Vining to find some ice, because I’m beginning to get nervous about the hot links in the saddlebag.

With the harsh budget constraints I’m operating under, actually spending the going rate of $2.89 for a bag of ice—most of which won’t even fit in my little cooler—is out of the question. The better alternative is one I’ve used under similar circumstances over the years, and that’s to schmooze the clerk at a gas station/convenience store into letting me fill a 32 oz. cup with ice from their soda dispenser and dump it into my cooler. I offer the clerk whatever they want to charge me, and generally they’re pretty compassionate about the deal, and in Lee Vining the gal hits me up for a quarter. My breakfast now assured, it’s back down 395, and back up the mountain to Obsidian.

Breaking camp

The sun tops the ridge to the east at 7:45 in the morning and I roll out to make my breakfast and pack this circus back up for the ride home. Two hours and two pots of espresso later I’m fully fed, fully wired and fully packed for the ride home. In traveling here I’d ridden Highway 128, did a short stint on I-80, and then took Highway 50 up to Echo Summit. From there I’d headed down Highway 89 over Luther Pass and then over the top of the Sierras at Monitor Pass. For the return leg of the gambit I’ve got the XT aimed straight up Highway 108 to the Sonora Pass—the Queen of the Sierra crossings. Topping out at 9,624 feet, Sonora Pass is second only to Yosemite’s Tioga Pass in elevation, and hosts a fraction of the traffic. Breathtaking vistas, mind-blowing granite formations, roadside waterfalls and deep frigid plunge pools make the passage a Sierra wonderland, and it goes on for miles and miles until you swear you’ll scream if you have to look at one single more spectacular sight.

Highway 108 sets me down at last in the heart of the Gold Rush country at sprawling Sonora, and then it’s a hot lap up Highway 49 to Highway 12 and a hot lap across the Central Valley. And I do mean hot. It’s over 100 degrees when I hit the foothills, and it stays up there for most of the remaining ride, and the Ulysses isn’t happy about it. And neither am I.

Under more temperate conditions, the bike’s hot-blooded tendencies—stemming from having its motor largely enclosed by frame spars/fuel cells and bodywork—never rise to the level of a comfort issue. The same can’t be said of motoring in this kind of heat, and the spars become wicked-hot to the touch. After awhile I have to assume a spread-kneed saddle posture to beat the heat. The seat gets warm as well, and I find myself scooching around to get some bum relief, an effort hindered by the coarse texture of the seat’s cover fabric. The XT gets admirable gas mileage, routinely returning a budget-conscious 50 miles and more on a gallon of high-test, and it’s easy to run three hours between fuel stops under normal conditions, but in high heat, an hour is all my cakes can handle at a stretch before demanding a break.

That discomfort is the first and only sour note the XT hits on this trip, and remains my only complaint of any consequence about the machine. That gripe is decisively overshadowed by the bike’s fearsome packing and sporting capabilities, and it’s those capabilities that get the real credit for this: Three days and 734 marvelous miles of riding, encompassing along the way four Sierra passes, Bodie and Mono Lake; two nights of solitude and reflection on a mountain stream with a bald eagle flyover and a late-night fireside snake-bite buzz beneath a meteor shower. All for the princely sum of… $104.80.

Damn. I went over budget. I have to try this whole thing all over again. Damn.