Our lifestyle in the gallery

An artistic link between rebellious generations

Santa Monica, Calif., Feb. 6—For so long, a motorcycle event referred to a rally, a bike show, a toy run, a poker run, a club gathering, a race or some other variation on the theme of chewing miles of road dirt before bellying up to a blue-collar bar for good times with the brotherhood.

Not any more.

The motorcycle and the motorcycle culture as art is a movement that has now officially emerged from the subtleties of framed campy ’60s biker movie posters and the underground appreciation of Dave Mann to become a full-tilt art genre that now takes place in well-known big-league galleries.

The latest showing within this nouveau-niche occurred on a night of rare Southern California heavy rain. The downpour surrounding the warehouse-like art colony that is the Bergamot Station Arts Center, situated in the always-eclectic city of Santa Monica, made for that perfect artsy ambience—displays of creative passion amid the intense forces of nature.

Entering the gallery, I almost wanted to cut off an ear, shave my hairy face into a pencil-thin mustache, buy a beret and jump into a serious study of cubism. But no! I didn’t have to do that to share in artistic inspiration this night; because, once again, the lifestyle I love was here for all to see and admire, in exalted gallery glory. It was leather and V-twins, not expressionism and still-life—la dolce vida!

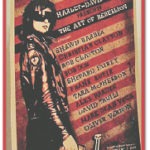

This particular journey into cultured sophistication came courtesy of the Harley-Davidson Motor Company, the Robert Berman Gallery, the charitable foundation Art Matters, and 11 of today’s most relevant and exciting artists who, according to Harley-Davidson, were recruited to present their take on the theme of rebellion.

Officially titled “Harley-Davidson Presents the Art of Rebellion,” the showing was twofold in purpose. On the commercial end, it was an extremely apropos way to introduce the latest offering in Harley’s Dark Custom series: the Iron 883.

I like this series and this style of motorcycle. I like the stripped-down primitive look. I like the flat paint, basic black appointments and the utilitarian exhaust. It says, let’s ride more and pose less. It also says that there are roots to this lifestyle; roots that should be explored before someone turns the key on a shiny brand-new motorcycle and calls themselves a biker. It says that there are roots going back to when most of us couldn’t afford five-grand paint jobs and when a lot of our bikes were put together—or at least held together—with the parts we bought at real swap meets or from the tilting metal shelves in real motorcycle shops with oil-stained floors.

On the aesthetic side of things, artists commissioned for the exhibit took a Sporty tank and made it an objet d’arte that represented rebellion—an edgy concept that has been a part of this lifestyle since even before Brando was asked the question: “What are you rebelling against?” in the classic flick, The Wild One.

His answer, of course, was: “Whaddya got?”

Well, what we got here at this event was a lot of different and interesting interpretations of an important commercial and social concept—one that Harley has now obviously embraced, both in image and in many of their new products.

And I think it’s a healthy trend at the corporate level.

Over the years, corners of criticism had existed that The Motor Company tried to distance itself from the very rank and file that had made the Harley-Davidson motorcycle a world-recognized icon and the manufacturer, and a storied financial success. In his biography, Hell’s Angel, Sonny Barger writes “To Harley-Davidson, we made motorcycle riding look bad. Even if we did, we also made them tons of dough for the notoriety of us riding Harley-Davidsons.”

But times—and things—have changed.

“If there’s anybody who understands self-expression, it’s Harley-Davidson,” says The Motor Company in official statements. “Harley supports the efforts of those who break ground creatively and artistically. In fact, Harley knows these ideals so well, that they created a collection of motorcycles called Dark Custom for today’s rebellious generation. Harley’s latest bike, Iron 883, is a raw and elemental bike built for those with a fire that keeps burning.”

And the factory is backing up those sentiments.

The new Harley-Davidson Museum opened last year in Milwaukee, with the entire gateway to the huge post-war bikes exhibit featuring as its centerpiece a factory-built vintage bobber that was designed as a tribute ’sickle to a very rebellious era in general, and to the legendary Boozefighters Motorcycle Club in particular. Glass cases nearby contain memorabilia from other clubs and all those rebellious pioneers who carved out legends and legacies on bikes that have inspired, not only the Iron 883, but H-D’s Cross Bones, Street Bob and others.

Whether this attitude represents an epiphany or has actually been the underlying H-D understanding all along is just another of those pieces of the legend that can be hashed over forever, along with the pros and cons of the AMF years and whether Harley ever really produced snow blowers. Either way, this exhibition—this lifestyle as art—was yet another nifty way in which what we do and what we enjoy is put on a somewhat mainstream pedestal to be appreciated by all as the very special thing it is.

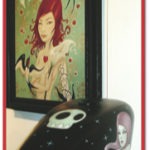

The tanks—the objets d’arte—themselves, made for a very diverse display. Each creator’s expression of rebellion was very cool to observe and absorb as a statement.

One common thread was that every tank fit the elemental tone of the Iron 883 and the Dark Custom series. None had that deep, seven-layer, 12-coats-of-clear, core-of-the-sun gleam. The base paint looked like something that could have been done by liquored-up good ol’ boys in a 1946 garage. The images of rebellion that leaped out from the bases had that hand-painted feel that made for such a direct, raw connection between the artist’s mind and his or her creation.

The tanks—and an accompanying piece of art by each artist—were all on sale. Proceeds from the purchases were destined for Art Matters, a charity that Harley-Davidson describes as supporting and encouraging the exploration of new ideas and art—a foundation that assists socially and aesthetically groundbreaking artists.

In another nice display of Harley’s appreciation of the edgy side of this lifestyle, the participating painters were lovingly referred to as a band of “lowbrow artists.”

I liked that, too. It was kind of like Garth Brooks’ brotherhood affinity for his friends in low places.

The lowbrows included Shepard Fairey, who created the very highbrow poster for the event; an extremely cool work that rivaled any high-dollar gallery opening print—you know, the kind that has something like a weird abstract picture of a skinny woman in a big hat with a bunch of French words. Well, Fairey’s poster was perfect. No abstractions or French; just a chick in leather, with shades, a smoke and a can of spray paint—rebellious and raw!

Fairey is indeed an interesting cat—an artist whose first works were spawned in the crazed skateboard subculture. His stuff has ranged from his famous Andre the Giant Has a Posse sticker art to the Obama Hope poster seen throughout the recent election.

The rest of the artists included Shawn Barber, Christian Clayton, Rob Clayton, Bob Dob, Frank Kozik, Tara McPherson, Alex Pardee, David Trulli, Mark Dean Veca and Oliver Vernon—a truly compelling and somewhat lowbrow bunch. Their artistic statements of rebellion ranged from politics to tattoos to tastefully naked chicks to rock ’n’ roll to a twisted take on Satan and much inbetween.

But one element of this night in particular struck me as an absolutely sincere, genuine attempt to extol the virtues of being lowbrow, rebellious and raw. There was only one brand of beer served at the open bar: Pabst Blue Ribbon. In tall-boy cans—no glass.

This was perfect. This was ideal.

I remember sitting with my father in the 1950s as he downed schooners of Pabst at Joe Jost’s in Long Beach—a lovable biker-friendly dive tavern that has been around since the Prohibition era in 1924, when new Harleys sold for $390 and a rebellious generation existed that was really not so different from today’s rebellious generation presented at the gallery.

Whether it’s the beer, the spirit, the creativity, the respect for our roots, the vintage, raw looks of H-D’s new models, or all of the above, it’s events like this that turn the spotlight on the timelessness of this lifestyle, and of the bikes we ride. Oscar Wilde said that life imitates art. On this night, in this environment, he was wrong. Bikers—true bikers—have never needed a media booster shot to tell them to be rebellious and self-expressive. This particular Art of Rebellion, in its reflection of our unique culture, proved that quite well.