Words and recent photos by Alan Shaw

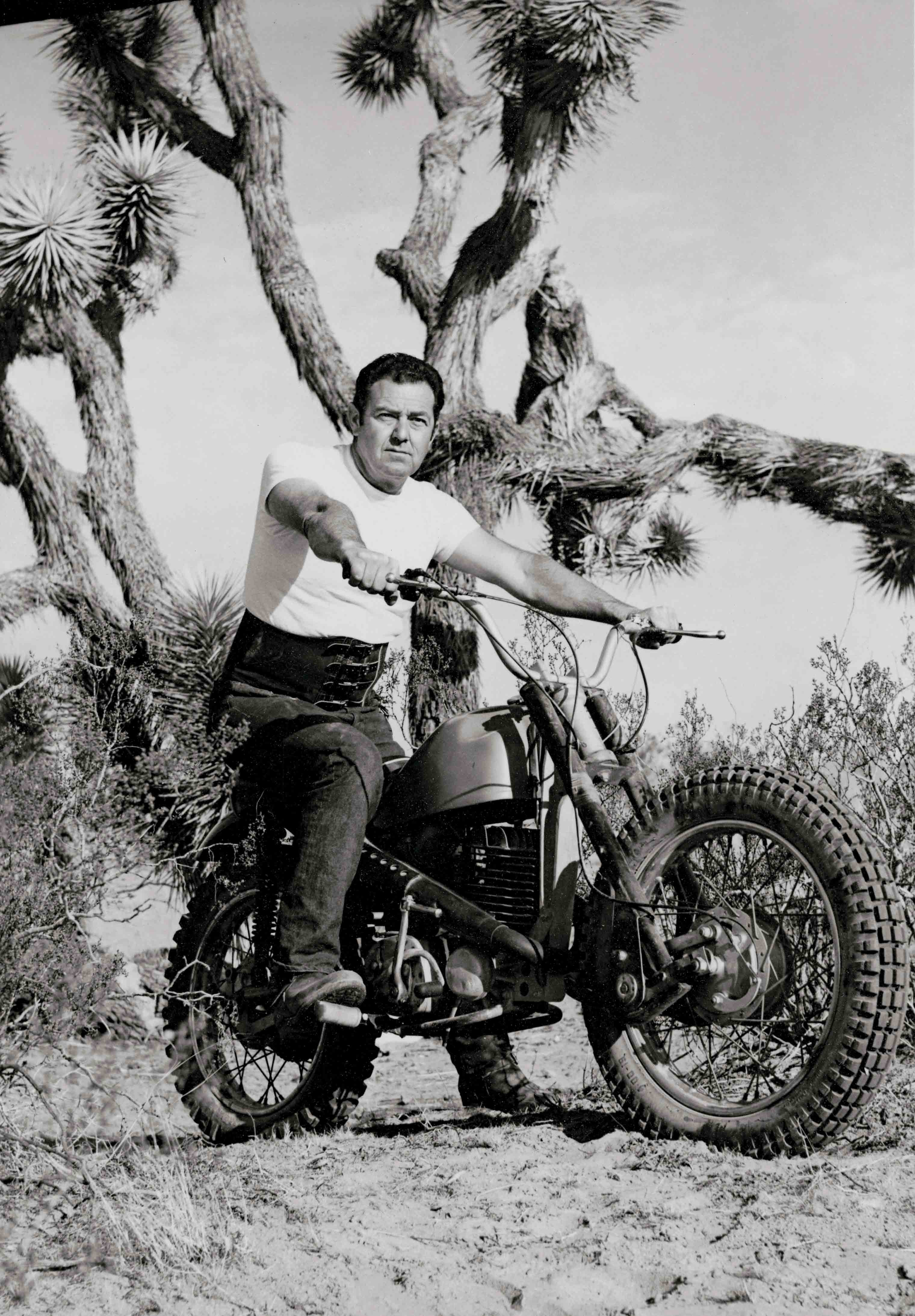

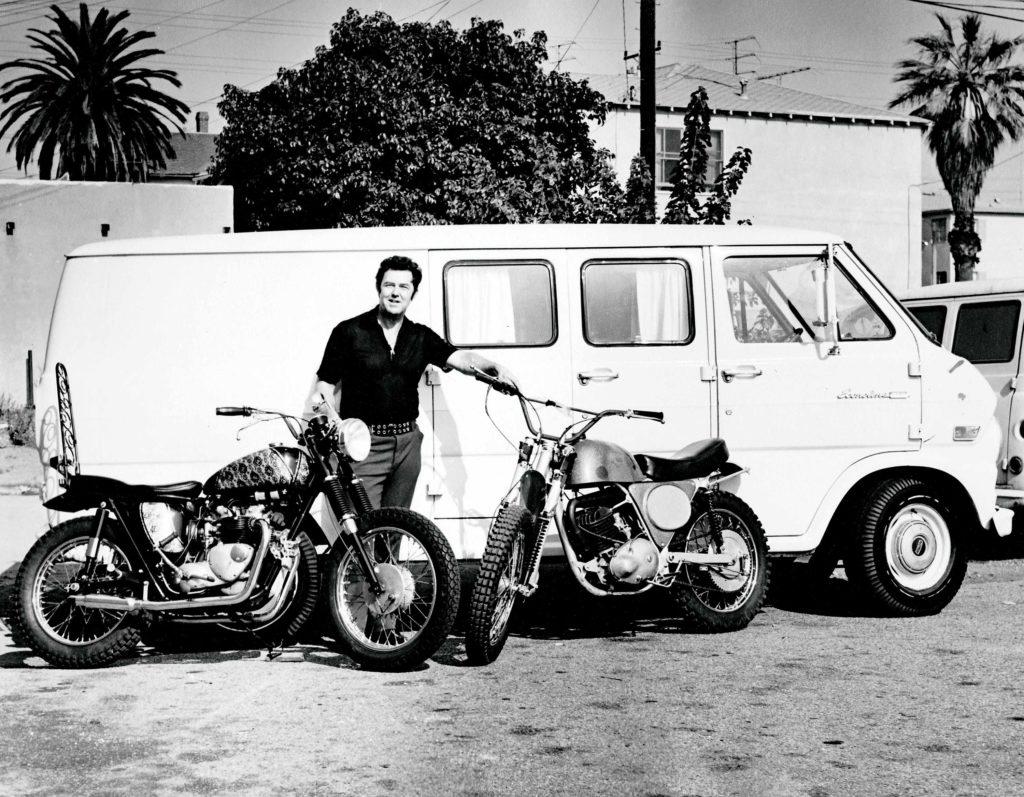

Earlier photos courtesy of the Carolus family

When the dust finally settled after the Gypsy Tour rumbled through the sleepy California farming town of Hollister during the Fourth of July weekend of 1947, more than 50 motorcyclists were reportedly behind bars with an equal number injured.

Overwhelmed by the 4,000 bikers who showed up for a three-day program of races and hill climbs, forty California Highway Patrol officers armed with teargas aided local police in dispelling a “riot” that left the streets littered with beer bottles and broken glass.

“If we jailed everyone who deserved it, we would have herded them in by the hundreds,” the San Francisco Chronicle said quoting the police.

Earl Carolus of the 13 Rebels Motorcycle Club was not one to be jailed. He had ridden up from San Diego that Friday on his Harley 45 Flathead with a couple of friends. He drank a few beers, watched some dirt races and hill climbs and then rode to Los Angeles to catch the Independence Day fireworks at the Coliseum.

While he did not hear about the media’s coverage until weeks later, he doubted the reports of violence and destruction.

“But you never know with those guys after they have had a few beers,” my old friend told me a few months before he died in July of 2018 at the age of 96.

Still, few people can claim to be eyewitnesses to history, or having participated, even minutely, in some of America’s most pivotal moments. And in the annals of motorcycle history, nothing is more steeped in our biker consciousness then Hollister. Many say it cemented the “outlaw” image of bikers in the minds of a sensitive public. While others say that overblown news coverage was used to sell magazines and turn public opinion against motorcyclists.

Earl believed the latter. So, just like how the character of Maxwell Scott said in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance?, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” This one is for you, Earl.

I really didn’t know Earl until about 2001 when he was approaching 80. At the time I wasn’t working really, giving up my suit-and-tie job, wondering what to do next. Yeah, I ran the full gamut: from a Vietnam Combat Vet to eventually landing a gig at the White House before moving back to California to give acting a shot. That was a bust, so here I was, sorta in semi-retirement, when I stumbled onto a few bikers hanging outside at a local coffee café, about a mile from Venice Beach. Earl was among them, along with his cohorts Steve, Richard, Jose, Oscar and a few others whose names evade me at the moment. As I recall, I strolled past their table, nodded and said “howdy” like I was living back in Virginia I suppose. After a few words were exchanged, they invited me to grab a chair, and I did. One thing led to the next and I started hanging out with them, going on rides, but as the years passed, many drifted away so it would be just Earl and me cruising up the Pacific Coast Highway and carving through the canyons, stopping at the Mimosa Café in Topanga, and then usually stopping at the famed Rock Store biker hangout in the hills north of Malibu. Earl actually preferred hanging at the Rustic Canyon General Store and Grill, a couple miles farther down the road on Kanan, as he didn’t like crowds much and it was more affordable. That’s the way he liked it: low key and quiet, although there was always someone who recognized him from somewhere so they would give him a glance and say hi. When I had his full attention we would talk about life and living in general, but I would always try to get him to tell me about the old days and what it was like growing up in a much simpler America.

Like a lot of old men who have been humbled by time, he didn’t necessarily want to dwell in the past primarily because he didn’t believe his story was worth telling.

“Nah, why would anyone want to read about me? I’m just an average guy who loved motorcycles; that’s all,” he would say every time before he spun a yarn.

Earl was born on December 11, 1922 near the town of Lynwood, California, which borders Compton in the southern portion of the Los Angeles Basin. Lynwood was fresh on the map, having been incorporated only a year earlier with its namesake honoring the wife of a prominent local dairyman.

As a child growing up around plenty of open roads and undeveloped farmland that was gradually populated with a forest of tall steel oil derricks, Earl knew early on that riding motorcycles was in his blood.

When Earl was only 10 years old, the owner of the machine shop right next door to his parents’ house fabricated a motorized scooter for him. New to engine-powered two-wheelers, he rode the hell out of that thing until not even divine intervention could salvage it.

Shortly after that, another neighbor taught him how to ride his 1928 Indian Scout 101. Manufactured from before the Great Depression until 1931, the Scout 101 has been called one of the best bikes Indian ever made, with its easy handling making it a favorite among racers, hillclimbers and trick riders. For Earl, there was no turning back. He was hooked and eventually bought that motorcycle from his neighbor. He recalled how he once took it out on the high school track, thoroughly tearing up the oval. His next bike was a Harley-Davidson VL. The VL was a Flathead twin that originally debuted in 1931 and quickly became a popular touring bike.

It remains unclear whether Earl graduated from Los Angeles High School in 1939 or not. Regardless, it was at the tail end of the Great Depression, when unemployment rates were still in the double digits, that Earl took a job at the Bethlehem San Pedro Shipyard. When World War II broke out in ’41, Earl was eligible to be drafted but was given a deferment because of his shipyard skills. San Pedro rapidly became a hub of activity, manufacturing a total of 26 naval destroyers during the war effort.

Just before the war ended in ‘45, Earl joined the ranks of the 13 Rebels Motorcycle Club. The 13 Rebels had already been formed by Ernest “Tex” Bryant and acclaimed racer Ed “Iron Man” Kretz in 1937, and soon attracted the now-infamous member “Wino” Willy Forkner. Back in those days, everyone was into dirt racing so they would strip or chop their bikes down to the bare minimum to reduce weight to increase maneuverability and control. Nobody added chrome and gadgetry back then, in part because nobody had any money. Besides, any money they did have went to making repairs, drinking, carousing and just having good-natured fun.

It was during this time when Earl became friends with Wino Willy, not that they were close, but close enough for Wino to ask Earl an important question when he was thinking about leaving the Club.

After the war, American motorcycling began to take off as returning military veterans sought a way to continue living on the edge. They had stormed the beaches of Northern France and beat back Japanese incursions throughout Asia and needed some way to blow off steam.

As part of the 13 Rebels, Earl participated in many sanctioned American Motorcycle Association races and gatherings—always shredding up the dirt track.

As San Pedro wound down and returned to civilian operations, Earl moved down to San Diego for a spell. He had a keen eye and was a photographer on the side. Both of which helped him with many of his “pin-up” girlfriends that he coyly convinced to poise for him, sans clothing. After seeing a display of his black and white work shortly after I first met him, I told him he should have been a Playboy photographer. I think he missed his true calling.

In ’46, Earl finally settled down and married a woman named Lois, who he met at the flat track races. She loved motorcycles too, so that sealed the deal. They had a son that same year named Lyle. Also, in ’46, Wino Willy—who split from the 13 Rebels to form his own club, Boozefighters MC— asked Earl to join him. But Earl declined because he wouldn’t be able to participate in AMA-sanctioned races and he was still a loyally devout Rebel.

Despite settling down with his wife and son, he managed to make it to Hollister for that fateful day in American motorcycling history that spawned a counterculture of rolled Levi 501 jeans, leather jackets and boots. It was a culture that polite society demonized.

As life went on, the pressure of providing for his family increased. In 1950, he and a friend went in on a restaurant in Bouget Canyon, but that venture fizzled and Earl bolted to Tempe, Arizona where, as a bartender, he managed to stay drunk most the time.

After a year or two in Arizona he felt his life was at a dead end, so he moved back to Southern California with his family in tow. They settled in Granada Hills, a suburb just north of Los Angeles. It was still the 1950’s when he got a job with Helm’s Bakery driving a truck. In the sixties and seventies, he worked a variety of jobs: installing sound systems, burglar alarms and television antennas. He was also an electrician before he retired. During those years he kept in touch with his biker friends, but he was too busy raising a family to do much else. After his son was old enough to be on his own, Earl and Lois rented a friend’s house in Venice just off Rose and Lincoln in 1975. He lived in that house for the rest of his days.

Now, just because Earl stopped riding with the 13 Rebels doesn’t mean his life became boring or that he stopped riding. And sure, Earl could tell you stories about those days better than me, but as I recall here are two funny tales he shared with me:

One time he was riding at the back of the pack with a bunch of guys going wide-open when he noticed blue and red lights in his mirror. To avoid getting a ticket, he immediately exited the next off ramp thinking the cop would rather chase after the pack and not one rider. He was right. From the top of the overpass, he smugly sat back and took in the view.

When he rejoined his friends, they wondered where the hell he went. Needless to say they were pretty pissed when he told them he enjoyed watching the cop giving them shit. And yep, Earl gloated when he was the only one without a ticket.

Another time, when Earl was in his 80s, he was speeding at around 85 mph on an open road when he got pulled over. The cop looked at his license, then at Earl, and back to his license and asked him if that was his real age. He nodded in the affirmative. The officer paused and said “I can’t give you a ticket. you’re old enough to be my grandfather and I just don’t have it in me to write you up.” Keep it safe and don’t speed anymore. Now get outta here before I change my mind!”

In the 1990s, Earl purchased the last bike he would own—a Sportster that he bored out and added some racing mods to. His wife Lois loved to ride as a passenger, but she passed in ’92 and he started to rely more and more on the Sportster. After 46 years of marriage, he would always pause to gather his emotions when we spoke about Lois. Earl started to take that bike everywhere, even to jam with his music buddies, strapping his old autoharp on his back.

Even as the years ticked up, Earl was never one to just sit back and cruise. He would chew up and spit out the twisties, leaving me in his rearview mirror. It wasn’t easy keeping up with him and I cherish those times. I lost my dad in 1971, so Earl kinda filled that gap as they were both about the same age.

Eventually, time caught up to the old rebel. He had already licked cancer and suffered a heart attack years ago, but this decline was different. One time he passed out on his bike at a red light and with Venice getting crowded, he grew tired of fighting traffic. After a minor sideswipe when a car merged into him, he decided enough was enough and he hung up his helmet for good at age 90.

Even though Earl lost a lot of his old photos of friends in a flood, he was okay because most of them were already gone. I told him at least he was still around and joked that he could hit 100.

“I hope not. I’ve already outdid my stay here,” he said.

In his last years, he walked everywhere he needed to go. Mostly a mile down to the waves and sand of Venice Beach, usually taking his dog along the way. Oh, and he would drive his car sometimes, even though the DMV took his license away for medical reasons. He still had that rebel “I’ll do what I want” attitude to the end.

We would often meet for coffee at a hole-in-the-wall coffeehouse on Rose Avenue where the regulars knew him. He was well liked and never without company. It was at that place, that I got to write down most of the details you are reading.

When I asked him what the secret is to long life, he said: “It’s bad luck. With my health I should have been gone a long time ago. You got to just take it one day at a time.”

It was around that time I heard the Boozefighters were hosting a memorial event, so I decided to ride up and pay my respects. I got to chattin’ with one of the members about Earl and he told me to bring him up to the Clubhouse sometime as he wanted to hear the stories about the old days with Wino and how it was back then. I told him I would as soon as Earl was feeling better. It was at this time that he had another setback and was bedridden. I thought he would soon recover as he had these bouts before. This time I was wrong.

The last time I saw Earl was on July 7, 2018, six days before he passed. I told him he had to get back on his feet because the guys from the Boozefighters wanted to hear about his days with Wino Willie.

“Who?” (he had his hearing aid out.) “You know, the Boozefighters,” I replied louder.

He grumbled a bit. “Oh, I dunno. Why do they want to see me? Besides all the Boozefighters I’ve known are long gone.”

Well, old friend, it looks like you got another chance to meet them. Tell them “howdy” for me.

His son, Lyle, took up riding from his dad, and has a Shovelhead that he scoots around the Redondo Beach area. Earl used to put him on his gas tank when he was a kid and ride him around the neighborhood and sometimes on the dirt track between races, Lyle told me.

His tricked-out Sportster now belongs to his grandson. Earl wanted it to stay in the family.

Earl’s favorite hangout when riding in the canyons “Rustic Canyon General Store & Grill” was destroyed in the Woolsey Fire five months after his passing. “The Rock Store”, just a couple miles away still stands.