A nine-month, 23,000-mile journey across America

Words and photos by Kali Kotoski

No Direction Home

It was near sunrise in Athens, Greece when I called my brother with a crazy idea. Earlier we had been out drinking and dancing at a large, open-air club at the base of the Acropolis and I was still riding high.

“What time is it there?” my brother asked.

“It is pretty early… but I want you to hear me out,” I said.

Back in Minnesota my brother had just returned home from high school and plotted for maybe an hour until my phone ran out of credit.

“You know how dad motorcycled throughout Europe for nearly two years in the 70s? Yes…camping out every night…seeing new stuff…Well, let’s do something bigger, or different, or whatever…some Jack Kerouac shit…ride across the U.S. like vagabonds!”

“Hell… Alright. Yes!” my brother said.

Living abroad was great but it made me realize how little I knew of my own country and I dreamed of aimlessly setting of on an adventure.

Also, I missed my brother and worried that we were no longer close–fearing that if we didn’t do something huge, adulthood would naturally push us apart. If we could pull off a trip of this magnitude, there was no question we could overtake our father’s legendary status. “Oh, we got some killer stories too, Pa!”

When I returned to Minnesota in the summer of 2008, it was a few months before the Great Recession tanked our father’s homebuilding business.

We had roughly 15 months to prepare for the road and to graduate from high school and college.

Our father’s lower vertebrae had finally disintegrated as a childhood injury left him lame, and us out of work. As he recuperated from an invasive surgery that sliced both from the back and front to attach metal rods to his spine, we worked on rebuilding the engine on my brother’s 1980 CB650 Custom and my 1981 Suzuki GS750GL.

I am a terrible mechanic, unlike my brother who understands the fundamentals. After painstakingly rebulding the top end of the GS750G, the engine seized at speed and nearly bucked me off.

While I avoided that premature ending, the CBR650 Custom was turning into a money pit.

But year later, I scooped up a 2004 Honda Shadow 1100 using graduation money and Weston found a 2002 Suzuki VL 800 Intruder Volusia. For months, we had been hyping up the trip. We listened to those who tried to persuade to give up the dream and focus on the materialistic pleasures of houses and sectional sofas. They said we were crazy, irresponsible and idealistic. And then there were the supporters, like our parents.

“You guys will cherish this trip forever,” our mother said. “I wish I was younger because I would be right there with you,” said our father.

We would look like chumps if we didn’t follow through, despite financial concerns and student debt.

Plus, we didn’t even have our motorcycle licenses yet, both having failed the test. Eventually we passed and (more importantly) I secured a fake ID for my brother from a friend that slanged dope. It was one of those expired IDs with the corners clipped.

By 2009, our father had finally recuperated, and we took a job remodeling our uncle’s old log cabin in Wisconsin.

We couldn’t have asked for a better way to train for the trip mentally. We spent the whole summer sleeping outside. My home was a hammock tent that I would slip into every night, sleeping peacefully until I could feel the cool lake breeze on my backside.

During the day we mixed cement, milled logs, built a roof, a porch and installed new windows. At dusk we would dive into the lake with a bar of soap to wash off layers of grime and swim until the grill was fired up. Then we would start a fire to warm up and watch it get dark and listen to our dad’s stories of youth.

Finally, the leaves started to turn red and we had to get going.

We packed two pairs of clothes, two sleeping bags each, bungy cords and rope for clothesline, steel wire, rain gear, boots, batteries, knives, a camping stove, matches, lighters, emergency blankets, wrenching tools, flashlights, tarps, maps, a compass, passports, insurance cards, bandages for blisters, hand sanitizer, wet wipes, a collapsible triangle saw and most importantly, a carbon hand pump water purifier from our dad.

All told, about a hundred pounds each stacked and strapped tightly to the rear saddle, fender and sissy bar.

To prepare, Weston shaved his beard into a cartoonish horseshoe, and we all agreed he looked like a sex offender.

We had one final breakfast together before we raised our kickstands. Everybody seemed excited, but right before we left, our dad asked us for a minute alone.

I had never seen such a look of terror on our father’s face, as if we had been drafted for a foreign war. It was just a momentary flash, but unmistakable. “This could be the last time I see my sons.”

“Be safe out there, alright sons? Be smart and ride safe…don’t ride at night if you can help it,” he said.

We crossed Wisconsin through some dense and tall pines and made it into Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and stopped at a campsite near the Porcupine Mountains. A nice 200-mile ride to mark the beginning.

New England

After crossing into Canada at Sault Ste. Marie, we hugged the coast of Lake Huron until meeting up with a friend in Toronto. Camping spots were plentiful, except near the town of Nobel where we got permission from a junkyard owner to grab a plot of land. With a clear forecast, we didn’t bother with the tent. The next morning, large brown slugs gripped the sleeping bags and had squirmed into our leather jackets, which we used for pillows. They wouldn’t shake off, so we had to pluck them with two fingers and clean off the sticky mucous.

It didn’t feel like we were on an adventure until we crossed back into the U.S. at Niagara Falls and rode through the rich, undulating farm country of upstate New York and into the Adirondacks, passing the decrepit concrete remnants built for the 1980 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid.

Then one night after riding, we realized we had logged over 1,500 miles and were the farthest we had ever been from home, via land transportation.

“Cheers, bro,” Weston said, knocking back a healthy gulp of whiskey as we huddled in the dirt near the fire. “We are really pulling this off and I had my doubts. But hell, we are free! We need to get drunk and celebrate.”

“I have a friend in New Hampshire, and she loves to party. We will be there soon,” I said.

The next day, we were soaked to the bone from a downpour and considered a motel but couldn’t find anything under $30—our budgeted limit. Our thin sleeping mats weren’t cutting it, waking up stiff and in pain, so we purchased two inflatable mattresses and a battery-powered pump from Walmart.

After following a muddy path along some railroad tracks in the Adirondacks, we found a nice cozy nook with a big evergreen for shelter. Weston dug out portable speakers and we performed a rain dance.The mood drove us insane and we leaped into big muddy puddles, wrestled on top of soggy grass and played a rock throwing drinking game. We were happy and ecstatic as the rain lashed through the trees and settled into a steady, windless downpour. I hoisted Weston up into the evergreen to snap off dead branches and we walked the railroad tracks looking for firewood. It reminded us of the kids from Stand By Me, except we were hunting for dead branches instead of a dead body.

But the fire wouldn’t start and were shivering from cold sweaty exhaustion. We tried birch bark, paper and kindling and nothing would light. We considered siphoning gasoline from our tanks and soaking our socks like a torch. Finally, we pulled out the battery pump and got a blaze roaring.

Soon enough, we were in Vermont after crossing Lake Champlain. Then Smuggler’s Notch north of Mount Mansfield near Stowe, New Hampshire and up to the top of Mount Washington. We spent a day making passes on the Kancamagus to admire the vibrant fall colors and test our handling of speed.

When we met up with my friend in Concord, we looked, and smelled, terrible, we were told. It had been four weeks since we did laundry and had been turning clothes inside out. Still, we were welcomed with open arms. My friend, Sarah, is a loveable, beautiful and bubbly woman who like me had just graduated from college. She is a Greek-American who I had met while living in Greece, and she is also incredibly annoying, prescription level neurotic and fun.

We spent a week with her and her family, sleeping in the basement with the wood stove. Finally, we went out to party, with my brother’s fake ID failing the only time of the whole trip. On to the next bar along with Sarah’s two very attractive friends (one that happened to be a cute elementary school teacher), and back to one of their houses to drink and laugh and indulge in passions.

“Why didn’t you come home last night? I stayed up expecting you all,” Sarah’s dad asked the next morning when we came through the door.

“Walk, [cough] walk of shame,” Sarah blurted out.

“What is that?”

“Oh, nothing dad,” she said.

Youth is a wonderful thing, I thought at the time.

“We’re Rhode Island born, we’re Rhode Island bred. And when we die, we’ll be Rhode Island dead”—Rhode Island Fight Song

The first pilgrimage of the trip was a visit to the Elder Ballou Meeting House and Cemetery in Cumberland, Rhode Island. Our grandmother on our dad’s side is a Ballou—a prominent family that helped settle the Colony of Rhode Island with Roger Williams, a minister who was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1600s for his heretical views about the separation of church and state. Williams formed the colony in 1636. As followers of his vision, the Ballou family became economically and religiously powerful. In 1749, Obadiah Ballou established the meeting house and cemetery on two acres of land.

We had a hard time finding the meeting house, and every gas station attendant we asked claimed to have never heard of it. Luckily, we stumbled upon Elder Ballou Meeting House Road and found a small stone marker indicating its historical standing.

Arsonists had razed the meeting house to the ground in the 1960s, but the foundation and graves dating back to the Revolutionary War remained.

For hours we studied the graves, some fresh and clean and others hardly legible. It was surreal to look at hundreds of years of dead relatives whose bones rested beneath us. Ezekiel, Asa, Levi, Jesse, Lilles, Dexter, Reuben, Abner, Beulah, Nathan, Levina. Soldier in the Revolutionary War, 1776; Minister, 1798; Landowner, 1814; Infant, 1752; Infant, 1840; Infant, 1867; Union Army Officer, 1861; Beloved Wife, 1890.

As it started to get dark, we decided we would sleep behind the cemetery, out of view from traffic and in the woods. We rode our bikes up the worn walking path and lifted the bikes one by one over a boulder.

After dinner, we went back down to commune with the dead. It was cold and foggy.

“This is super creepy. I don’t like it at all,” I said. “Like, I know it is nothing, but this is sacred ground.”

“Yeah, I have the chills,” Weston said.

After taking turns at who could stay silent the longest next to the graves, we decided we should turn in for the night. In the tent, we rolled cigarettes and tried reading.

We didn’t know this at the time, but the Elder Ballou Meeting House is one of the most haunted places in New England. Besides rumors of ghosts, UFO sightings in the 1960s were popular in local papers. It is also home to the urban legend of Freddy Fingernails, a spirit that haunted the Ballou Cemetery and Cumberland. The legend dates back to the mid-nineteenth century and claims that a reclusive homesteader, Freddy, swore revenge on three boys that burned down his house, with his ill daughter still inside. Freddy was disfigured and some claim he was the inspiration for the Nightmare on Elm Street movies.

“What was that?” Weston said with just his mouth sticking out of the sleeping bag and his eyes covered. I could see his breath in the lantern light. “It is a beeping. Beep…beep…beep. You hear it?”

I heard a phone ring.

“What the hell?” I said.

“I don’t know. Listen…now you hear the beeps, like the battery is dying.”

The ring was close and distant at the same time, or at least it seemed in darkness. We were accustomed to inexplicable wilderness sounds, but this was a human sound. It rang again and then beep…beep…beep…silence.

We jumped every time it rang, seeing we had just played around in an ancient graveyard and ridden our motorcycles through it. Scenarios of a dead body hiding in the forest came to mind, grizzly and mutilated.

“Screw it,” Weston said, and we armed ourselves with knives and flashlights. It was 3 a.m.

Ring, beep…beep…beep.

“Let’s go! Now!” Weston said as we sprang up and bolted in the direction of the sound.

We hunted for the cellphone for hours, jumping at every ring and searching the darkness. We kicked through tall wet grass, struggled with branches clawing at our faces and made hand signals to stops and try to pinpoint the beeps. The sound wasn’t coming from the cemetery but deep in the woods.

We didn’t sleep that night until sunrise.

In the morning, we could see our tracks in matted grass. We thought we had strayed far, but in reality, we never went further then 50 yards from the tent. Still expecting to find a body, we talked over what we would tell the police, which sounded absurd. A couple of vagrants found a body. Just passing through. Carrying enough camping equipment to tie up and dismember a corpse. Just a couple brothers from the Midwest with no alibi.

Eventually, we found some large boulders with a fire pit in the middle and cases worth of empty beer bottles scattered around. Some had been broken against the rocks, empty cigarette packs stomped into the ground.

“Stupid drunk teenagers partying near a cemetery. Absolutely no respect,” I said looking at the mess.

“Like you in high school at the church when you got arrested?” my brother asked. “The second time, not the first.”

Get out of the tent! Hands up!

From Rhode Island, we rode south passed New York City and into Pennsylvania via the Delaware Water Gap.

My brother and I were getting along pretty well, but cracks were starting to form. I had been calling the shots and treating my little brother like a little brother.

It started to boil over when he signaled for us to stop on the shoulder of a busy freeway.

“Are you telling me we aren’t going into New York City? Why the hell not? We can see it from here,” he said pointing at the metropolis in the distance as traffic zipped by. “When else are we going to have a chance to ride into there?”

“I just don’t feel comfortable with the traffic there and it is too expensive,” I shouted.

“You know that is bullshit,” he said. “Stop being weak.”

Weston and I are extremely different and while growing up, we reinforced those differences. We had explosive, and violent levels of competition. But we are also extremely similar. I have a long fuse. My brother, a short one. That means that the end result is always the same, just depends on what lights the spark.

In Pennsylvania we passed the Amish in buggies and went to Gettysburg to tour the battlefield. Then to Washington D.C. to meet up with a friend. We marveled at the capital, the museums, the architecture, the power of the richest nation human history has ever seen. The Holocaust Memorial Museum was deeply depressing and embarrassing to feel how evil we can be.

After a few days in Washington, we crossed the Chesapeake Bay Bridge to explore the Delmarva Peninsula. It was mid or late November, and the weather was still pleasant and we went to a movie, Harry Potter, I think.

So far, we had been very careful in choosing our camping spots, making sure that we were never visible from the road. We often would have to scout out three or four possible spots to make sure we could have a cooking fire. Houses couldn’t be within view, never out in the open, especially along the densely populated East Coast. We also knew state forests were most promising, with few restrictions.

There were few options that night after the movie, and eventually we decided on a path with an open gate leading into the forest. We rode a couple hundred yards back, turned down a deer trail and found a small cramped spot.

It was humid and we slept in our underwear.

When I awoke from the light, I thought it was way too early for sunrise.

“Whoever is in the tent get out now with your hands up!”

“What? Who the hell?” one of us replied.

“This is a Maryland Police Officer. I said get out of the tent with your hands up and don’t make any sudden movements. I have my weapon drawn,” the officer said. “How many of you are in the tent?”

“Two. Just two,” I said.

“Male and female?” the officer asked.

“Two males,” I said.

“Hurry up and get out of the tent,” he said.

“Okay, okay, relax… we are pretty much naked so let us slip on some clothes,” I said, trying to find my jeans. I couldn’t get my zipper to close before stepping out.

“Jesus,” the cop muttered.

I could see the officer’s gun pointing at me from his waist.

“You can put that down,” I said.

“What are you two doing here? This is private property,” the officer said.

“We thought it was a state forest,” Weston replied.

“A state forest with a gate at the entrance?” said the officer.

“The gate was open, and it wasn’t posted ‘No trespassing,’” I said.

“What were you two doing in the tent?” the officer asked.

“What do you think? We were sleeping,” I said.

“Two men, with Minnesota plates, sleeping out in the damn woods. Is that right? This is Maryland, not some city where anything goes,” the officer said.

“We are effing brothers, officer,” Weston said.

“Watch your mouth… You, the big one, give me some identification and then step back. You, the small one, wait for him to step back and give me some ID,” the officer said.

“I’ll be damned. You two are brothers,” he said, visibly relieved. At some point he had holstered his pistol. “Okay, so what the hell is going on?”

We gave him the whole shtick, riding around the country, visiting friends, wanting to explore the Chesapeake Bay because we had always seen it in movies. Told him we were on our way to Virginia Beach to see a friend that served in Iraq, which was true, and that we swore we thought this was a state forest.

After a condescending lecture and performance, the officer said he was originally from Georgia and that two men sharing a tent “is just something we don’t like to see.”

At this point, the adreniline had faded and we were barely awake and sick of the officer’s blatant homophobia, but we remained silent despite the look of contempt on our faces being far from apologetic.

“You aren’t getting a ticket, but I want you out of here. You got five minutes then I am following you to the county line and I want you out of the state by sunset,” the officer said.

He actually did follow us to the county line, pulling a U-turn in pure cinematic gold once we crossed. We rode for 20 minutes or so and stopped at a rest area to cook rice for breakfast. I can’t recall what happened next, but one of us said something, and then another thing and Weston exploded. He tore out of the parking lot leaving me there to fume and curse. It was something about how I wasn’t respecting him, or how he disliked the way I treated him compared to how I acted when we visited friends. Or something not like that at all, where I arrogantly mocked him. Something sharp and deeply critical. As he sped off, I was so angry that I could have cared less if he turned headfirst into oncoming traffic.

After I cooled down and got my thoughts straight, I searched for him in the next town for about an hour and feared that he had just kept on going. I panicked until I saw his motorcycle parked outside of a laundromat in a strip mall. We reconciled and fell asleep for a couple hours on the laundromat’s tiled floor. Women stared down at us while they washed and dried their clothes.

Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

Some of the best riding we encountered was on the Blue Ridge Parkway, which we connected with at the town of Boone, North Carolina after visiting our military friend and his family in Virginia Beach. Our friend Sean had served as a US Navy Corpsmen in Iraq and seemed well-adjusted. In high school, he was a skater kid and a druggy like the rest of us. But now, he was a father of two and a literal giant.

From Boone, to the town of Murphy in southwestern North Carolina, we zipped in and out of the mountains where the camping spots were plentiful without a single day of rain. The leaves were still changing, and the riding was fun and challenging, especially when we spent a day riding the Tail of the Dragon at Deal’s Gap. Ditching our gear and testing our limits, we furiously scraped pegs and felt truly alive and in control. It was that feeling of pure pleasure and happiness that never lasts.

A couple days later Weston got a flat rear tire near a small Appalachian town. The town didn’t have any services, but luckily we struck up a conversation with a bearded gentleman that said he could patch it up at his home. We spent the afternoon in his cluttered barn filled to the brim with worthless rusty cars and machinery and learned the proper way to say Appalachia. Over a few beers, he spoke of local problems, like the ubiquity of methamphetamine and opiod use and fewer job opportunities—the overall decline of the American dream.

Our next destination was Charleston, South Carolina, where we planned to stay for a month and find some work before heading down to Florida to stay with our aunt and uncle.

As we approached Charleston, a tropical depression was battering the coast. Drenched, we found a public library and searched for rental listings on craigslist.

“I don’t have a room to rent for as little as four or five weeks, but I got a garage at one of my properties on James Island that I could do under the table,” the women said. “It doesn’t flood in there and it has a bed with clean linens.”

The house was about 15 miles from our location, and the rain was making visibility near impossible at high speeds. To make it worse, when we got off the freeway, the rear-tire Appalachian flat-fix failed on Weston’s motorcycle and he had to quickly wrestle control of the bike.

We knew we shouldn’t press on after examining the tire, but the thought of a warm shower and a dry bed with actual blankets and washer and dryer and a proper stove and microwave was too promising. So, we filled up the tire and persisted. As the pressure dropped, Weston went sliding back and forth on the road and I signaled traffic to give us a wide berth. It almost ended horribly when a car cut Weston off and he had to pull a professional maneuver to stop from going down. Up went the middle fingers and other violent gestures.

At the house, we met our new temporary roommates, David and Zeke. Spanish moss hung thick in the property’s trees, the lawn was flooded, and geckos had invaded our room—the garage.

Our father had served at the Charleston Naval Shipyard in the late 1960s after he enlisted at the age of 17, when he was still a young brawler like Weston. He was stationed on the USS Fearless—an aggressive-class minesweeper that was built with a wooden hull for magnetic sweeping—as an electrician. The Fearless was launched in 1952, when our dad was 5 years old, and participated in NATO exercises in the Mediterranean during his time aboard.

When our dad was in Charleston, segregation had only recently been abolished and despite the shocking level of inequality he witnessed as a Minnesotan less accustomed to blatant racism, he would speak fondly about the architectural beauty of the city and romanticized Southern hospitality. To me, racism seemed alive and well. One afternoon I enjoyed a beer in downtown Charleston and was appalled when a well-dressed black man was denied service. “We just don’t serve them,” the bartender explained when I protested.

With a roof over our heads, we took to maintaining the motorcycles. Changing the oil, checking the fluid levels, getting new tires and waxing and polishing out the scratches on the bikes. We also inspected all the camping gear and reinforced the zipper on the tent. The neighbors would come by to chat and we would have pleasant conversations about the freedom of the road.

We also found the devil in the form of Kentucky Gentleman—a poison so unholy and cheap that its only benefit is that it teaches the drinker a lesson. A lesson of who they don’t want to be as that “bourbon” nurses demons.

One night David, Weston and I brought the Gentleman out to a house party and proceeded to make fools of ourselves.

After breaking a glass table, we were shown the door and decided to take a shortcut home through the woods. David is a great guy, warm, energetic and full-blown crazy in that foot-stomping, knee-slapping, hooting-and-hollering way that leads to awful decisions.

David led the way, and we flicked our lighters. We were soldiers on a mission until we ran into a 12-foot-high chain-link fence topped with barbed wire. David was convinced we could climb it and Weston volunteered, tossing the Gentleman over.

Up he went and down he fell, hooking his jeans near the thigh and slicing right up into the crotch. From our side of the fence, Weston looked like a mound of dirt. For an instant, we considered calling ambulance. But he finally stood and came close enough to the fence. Blood trickled from his forearm and Weston carefully inspected his leg and crotch to make sure everything was intact.

“That was too close,” he said, calmly. “There is no way you two are climbing that.”

“How are you going to get out?” David asked. “What if we climbed up and tried to pull you back over to this side?”

“No. No way,” Weston said, finally inspecting the shallow gash on his arm and applying pressure. “I will meet you at the house.”

We laughed at our stupidity and then Weston vanished. I had given him my cellphone in case he got lost. By the time David and I made it to the house it was 11:30 p.m. David ran to the garage, planning to belly flop on Weston who was surely passed out.

“Kali! He isn’t here,” David shouted. We searched the rooms, even checking the front lawn and backyard, thinking he may have lost his keys.

“He’ll turn up,” David said. “We still got time to make it for a few before last call at the bar.”

It was 1:30 a.m. when we returned, and Weston was still missing. We tried calling my phone, but he didn’t answer.

In Weston’s condition, we figured one of two things could have happened. Either a cop picked him up and brought him to jail, or to the hospital for detox. A sinking feeling of dread sobered us up.

David grabbed the phone book and flipped to the emergency services page. We called two police stations and three hospitals.

“Nobody by the name of Weston Kotoski has been admitted into the hospital?” I asked, trying to stay calm. “Please ma’am, can you check again. Yes, we last some him three or four hours ago. No ma’am, no drugs, just been drinking.”

There was no way we were going to sleep without finding him. And at 3 a.m., David packed a backpack with beer and we went out to retrace our steps.

We made it no further than a block when I tried calling Weston with David’s phone one last time. The ring was close.

“Are you kidding me!” I said as we walked toward a neighbor’s garage.

There was Weston, splayed out flat behind a tree, with the Gentleman still in hand. We slapped him awake and got him on his feet. It took both of us to steady his steps.

“Weston, what were you doing there?” I asked.

“I saw you two walking to the house, so I hid and was going to jump out and scare you,” he said. “Must have passed out…”

After two job interviews, one at an auto parts store and another at a mall, I gave up trying to find work as they had no interest in hiring a “Northerner.” They even tried to claim that I was a Canadian trying to steal jobs during the Great Recession.

Weston, however, landed a gig with a lawn maintenance crew. Starting at 6:00 a.m., he’d weed whip the ditches, remove dead branches and kick rocks at alligators. He maintained the area around the Naval Weapons Station Joint Base Charleston and its nuclear power training facility, which was a couple miles north of the shipyard our father was stationed at. It was hard, good paying work and under the table.

“Maybe it is the culture, but man, people are really lazy down here,” Weston often explained. “I am typically covering double the area than any of the other guys. You are not going to believe this, but the boss watches porn before work in his truck, pounds two tall boys and then gives us the day’s orders.”

I welcomed the chance to relax after four months on the road. I would stay up late with David and Zeke, not waking until noon before heading to the beach to meditate and read. Understandably, Weston thought he was getting hosed.

It was easy to blame the work as the cause of the problems, when in fact all the animosity we held against each other was ready to spill out and wreak havoc. Meanwhile, Zeke—who didn’t seem happy with his life, having recently been dumped and playing shows at local pubs like a Jack Johnson wannabe—was planting ideas in Weston’s head. “You don’t need your brother. He is holding you back and you are standing in his shadow. Be your own man. It is your money.”

That next Friday, Weston and I pre-gamed with the Gentleman and skipped dinner to watch college basketball at a bar that served free popcorn. When I came back in after a cigarette and chatting up some ladies, Weston was already chest to chest with a short, but solid, dwarf. The dwarf’s two friends were ready to spring.

“You feeling froggy? So effing leap!” Weston shouted, using one of David’s favorite catch phrases.

As I stepped in to try to defuse the tension, I caught the look in my brother’s eyes. I have had that same look before. It was that dangerously primal look when drunken rage causes the brain to short circuit.

“I don’t like these guys,” Weston said. “They think they own this place and wouldn’t stop pushing into me to get to the bartender.”

“We were just trying to get a drink and you started talking shit,” the dwarf’s friend said. “We will kick your ass!”

I barely convinced Weston that we needed to leave. Together, we were formidable, but simple math gave us low odds.

As we walked home, I lit into him.

“Weston, what the hell were you thinking? You think you can just fight anybody? You are a damn child and I always have to take care of you. Are you stupid or something? It is a burden to be always watching out for you, holding your hand. Bailing you out,” I said.

“Drop it Kal. Drop it,” Weston said. “I am warning you.”

“We are on the adventure of a lifetime and you are always pulling this crap. I thought this trip would make you a man. Be responsible, but instead you just get piss drunk and angry for what? For why? If you are going to fight someone fight me, not some random dudes,” I said.

By this time, we were crossing an empty church parking lot.

“I didn’t even want to come on this trip, but you forced me. It has been a waste of time and money and you are doing nothing while I am working my ass off,” he said, turning to shove me. “I am missing out on a year of my life. I should be in school but instead I am here, with you. You are so damn spoiled you don’t realize it. Oh, Kal wants to go abroad, while I work for dad. Oh, Kal wants to do this. You don’t care about anybody but yourself. Everything is always about you!”

“You are an idiot! A total piece of shit. Everybody knows you are the screw up in the family,” I said, knowing that I was lying but trying to hurt him. “Now what, you going to pump your chest? You want to fight me? Hit me! Do it! I dare you. But you are just too much of a…”

That was the last thing I remembered before coming to and seeing Weston over a block away walking beneath the Spanish moss. I was dizzy and disoriented. My jaw felt backwards. I didn’t remember him winding up, connecting, or falling to the ground. But the church looked weird from my angle. As soon as Weston hit puberty, he had one singular goal that inspired him to lift weights, learn to box and play football in high school. It was to be able to beat his older brother.

And there I was, unable to stand after an easy 900-pounds of force from a long right haymaker hit me right on the button. The type of haymaker, with feet firmly planted and hips and torso working in fluid unison, that was more of a shotgun slug than skin and bone. Plus, Weston is one of those lucky people that are blessed with bricks for hands.

Back at the house, I kicked holes in the wooden side door to the garage and Weston ripped my hammock tent. David came home and we wrestled Weston to the ground after he started breaking kitchen plates and glasses. A foot went up and David got a boot to the chin. “It is either you or me, but it should be you,” David said to me. I hit Weston in the face probably 25 times before David stopped me. The first 10 were full force, but then I started to feel bad. Weston stood up and went to bed and David and I cleaned up the blood. “He isn’t going to remember this in the morning,” David said. “You could see that in his eyes.”

The next day, I divided up the gear and rode to Savannah, Georgia with no intention of returning. It was Thanksgiving weekend and hotels in the historic downtown were full. Savannah is a weird place. The historic downtown is just as opulent and beautiful as in the movies, with large open square parks and confederate statues. Meanwhile, on the northern side of the Talmadge Memorial Bridge is a post-industrial wasteland, brimming with poverty along Bay Street.

I found a cheap motel that flew a large American flag on Bay Street. An Indian couple ran the joint, with paintings of their Hindu deities hung on the wall, behind a thick pane of bulletproof glass. I noticed various brands of condoms taped to the inside of the glass.

Earlier, I had asked a police officer if it was safe to stay across the bridge. “It should be, but that is where all the minorities and prostitutes live and you’re a white guy. Stay on this side if you can.”

I tried to get the Indian to give me back my card as he swiped and swiped, but it was too late and the payment went through. I backed my motorcycle close to the motel door and a woman sauntered by, holding a can of beer.

“You need any company in there tonight?” she asked.

“No thank you,” I said.

“Oh, sure you do. We will be in there later, honey. Don’t you worry about that,” she said.

I laid on the bed and turned on the TV. I tried to relax and reached for Kentucky Gentleman in my backpack, but it wasn’t there. I left it in Charleston and panicked because Georgia stores are closed on Sunday.

Then the phone rang in the room, startling me. It was a woman’s voice.

“Hey Mike, longtime,” she said. “Everybody has been waiting for you to show up.”

“Sorry, but this isn’t Mike,” I said, wondering what she meant by everybody. Besides the woman offering her services, the motel was a ghost town.

“Come on Mike, we know it’s you. Who else comes here on a black motorcycle? You been missing for weeks,” she said.

“I am sorry, but I really don’t know what you are talking about,” I said, disconnecting the phone from the wall.

That night, I had never been more scared in my entire life and the anxious hangover and concussion didn’t help. I became convinced that a small circular hole in the wall was from a bullet.

Two men came beating on the door and I eyed them through the peephole. It was dark and I couldn’t see their features.

“Mike! Open up man. We don’t need this to get ugly,” one said.

I turned off the lights and the TV. It was pitch black.

The next time they tried breaking in, I was more prepared, clutching my buck knife and leaning on the wall next to the door so that I would get the first move if the lock gave way. Thud, thud, thud. The door flexed, and judging by how loose the handle was, it had been kicked in before.

“Come on Mikey! We will destroy your bike if you don’t come out!”

They retreated from the peephole and I prepared to storm out if they touched my motorcycle. Luckily, they didn’t.

“Thought Mike had a Harley,” one of them said. “Nope, this is his. Has to be,” the other said.

An hour later, they tried again and again I stayed quiet and cursed myself for being a fool and wished I was anybody but me and anywhere but here.

The next knock on the door came near dawn.

“Sir, are you okay? Sir, I think people have you confused with someone else, so I am just checking on you,” it was the Indian owner this time. I stayed silent.

As soon as it was light, I rode back to Charleston and was never happier to see Weston, who wasn’t as bruised as I expected.

“Livin’ la Vida Loca”

David and Zeke were sad to see us go, as we had all become close friends. The neighbors threw a huge oyster roast for New Year’s before we left. Salty warm oysters, bushel after bushel poured into the cooking pot with beer. Saltine crackers, tabasco sauce, oysters and vodka. We hugged the friends we had made and friended them on Facebook.

In Florida, we stayed with our aunt and uncle in a retiree complex in Bradenton, outside of Tampa. As retired teachers, they had mastered old age while always keeping themselves busy learning new things.

Weston and I still fought, but instead of overturned tables and shots to the jaw, we took out our frustrations by…playing tennis, four hours a day, every day. Our parents flew down for a week to escape the Minnesota winter and they encouraged us to see the trip all the way through. They also gave us money.

After they left, we went to Miami for a week to stay with a high school friend that had a penthouse with his Mexican roommate, Jhordy. The four of us got our asses kicked by bouncers over a misunderstanding, and paramedics cleaned us up and let us go. My friend’s Cuban neighbors took us fishing for a day, and Jhordy (a pilot in training) got his instructor to take us up over the city. Some other things happened in Miami, which led to a turning point with my relationship with Weston. We learned no matter what the secrets are, nothing would stop us from being brothers. Then we got the DTs in the Florida Keys.

My high school friend John was a sound technician for Carnival Cruise Lines. He had already spent a couple years at sea, and we rode to Tampa and met him and his Australian-Chinese girlfriend at a Hooters near the port terminal.

The plan was simple. To get on the cruise ship for free, John would register us as stepbrothers because he was allotted to give four free trips a year, but only to family.

“Nobody really checks if we are related and plus, I know everybody that works on the ship,” he said. “Okay good, the only thing though, is my girlfriend is a dancer and we have this end-of-the-cruise karaoke performance and nobody ever wants to be Ricky Martin. So, Kal, you have to promise that you will sing in front of thousands of people.”

I agreed, thinking it was a joke and looked forward to venturing to Mexico, Belize and Honduras. It wasn’t a joke, at all.

Staying in crew quarters beneath deck is like a microcosm of the world. There were so many different races and ethnicities on the ship, divided by language. The Italians in charge of steering the ship stuck together, same with the Filipinos that cooked and made up the suites, while the Americans, Canadians, Brits and Australians in charge of handling entertainment, were one group.

John had already fixed the karaoke competition by the time they dragged me to the tryouts. If anybody else wanted to be Ricky Martin, they would have to book another cruise, paying customers be damned. I sang terribly and Weston and John booed and heckled me from the crowd. “Get off the stage you hack!” John yelled.

“Hey! Give him a chance! This is all about fun,” one guest yelled back.

After that failure, John took us to down to his room and gave me a tape recorder.

“During the show, there is no screen so you have to memorize the lyrics and I am worried that you are so bad right now, like way worse than I imagined, that you will embarrass me,” he said.

For the next three days I practiced over and over, singing in our cabin, which drove Weston wild. He endured the pain, but barely. Honestly, the night he fell off the top bunk and landed like a dead fish on the floor, I was more convinced that he wanted to die rather than turning in his sleep as I continued to sing.

Finally, the day came for the performance and at the backstage bar I crushed six shots of whiskey in less than five minutes. The anxiety was killing me.

“AND NOW, WE HAVE KALI KOTOSKI AS RICKY MARTIN, THE LATIN SENSATION OF THE NINETIES!” the announcer yelled, and I stepped into the spotlight. John and Weston had made signs to distract me and I quickly found them in the crowd.

I went all in, singing and shaking my hips in that stilted white way of dancing. I got a standing ovation from middle-aged women and they said I was a heartthrob and acted as if they swooned when they passed me after the show. I could have died happy that night, as I had reached my apex and anything I was going to do during the rest of my life couldn’t beat that moment.

It wasn’t until we reached New Mexico that Weston finally admitted that he was jealous of the experience, as if I had a choice.

It was late January when we finally reached Texas, stopping only in New Orleans after we left Tampa. We crashed with a friend in Houston, got a hotel room in San Antonio and then rode straight to Big Bend National Park along the Mexican border.

Out in the desert along Highway 10, before turning south to Big Bend, everything seemed new and fresh and revitalizing. We were back to riding every day and talking little as we reached moments of Zen with the road speeding beneath us. It was peaceful. All the drama of the East Coast, and the proximity to civilization that caused it, was stripped away by the vast openness of the country. A thin horizon in the distance, travelling west into the burning sun with everything we could ever need strapped on the motorcycles. It only took 10,000 miles for us to remember why we were doing this and to regain those uncorrupted feelings that inspired us in the first place. When camping, our conversations were now like philosophical undertakings, talking about what we had seen and the books we read and remembering our childhood. The bickering was gone, and we weren’t just brothers, but friends.

After I ran out of gas in the middle of nowhere, we each started carrying an extra gallon of gasoline in our saddlebags. Neither one of us had ever been to a desert before and the absence of life was purifying.

The Stillwell Ranch and RV Park outside of Big Bend sold tent spots for only $5 a person, per night. But the old, unfriendly woman that ran the place seemed hellbent on playing the role cowboy. The office was old and the wood was stripped of paint.

“Alright boys, you got three nights and can extend to four if y’all like. But no funny business. Power goes off at 7 p.m., dinner is early. Make sure you have water and if you plan on doing anything criminal, I will call the sheriff because in these parts, the sheriff still means business,” she said.

“What do you mean?” Weston asked.

“We been having a lot more drugs coming through this way and some of the folks I let stay here have that look of no-good on their faces,” she said. “I won’t be tolerating anymore of that kind behavior at my establishment.”

The next day we went for a long, 14-mile hike to the South Rim of the Chisos Mountains, a 7,400-foot cliff face where the sweltering dry wind from Mexico makes it feel that if you jumped, you would float back up. We didn’t have proper gear for this strenuous hike, or enough water, so that by the time we finished, our eyes were messed up and everything in the distance seemed to be bobbing up and down as if we were on a ship. Weston, in far better shape than me, was less sore and wanted to go for another hike after we had root beer and water.

But when we approached the bikes, we noticed two Harley’s had just backed in next to us. We had never bothered to back in, because we didn’t care about looking good.

“Who the hell taught you to park you bike like that,” the biker said, wearing a denim vest with confederate flag patches and a large knife hooked to his belt.

“Really man? You got a problem with how we parked?” Weston said.

“I see you boys are real far from home. From Minnesota, it looks like,” the biker said, mischievously. After that, the mood grew less tense and before we left, he offered to let us stay with him.

“We brought our truck and trailer and are camped down on River Road to the south. You should come out tonight. Road is perfect. And let me tell you a little secret, you can ride from there straight into Mexico for about 50 miles with no border patrol. I know this pharmacy down there where you can get all kinds of stuff that you can’t get here. No problem whatsoever. Think about it and I hope to be seeing ya.”

We said sure, knowing that we weren’t going to head down there. The guy reeked of trouble. That night, Weston and I had never before felt such drastic temperature swings, going from the low 80s with sun to below freezing at night and staying cold until the afternoon. We imagined it must be similar to the surface of the moon.

We stopped at the park office to ask a ranger about River Road on our way to the Santa Elena Canyon.

“He said to take you bikes down River Road? That path is only for off-road Jeeps and is in the middle of nowhere. Drive down to Mexico from there? No, no, no. This isn’t right. You boys are lucky because we get a lot dead bodies out of that area and he could have taken your bikes on his trailer and left you for dead. That is a good 30 miles into the desert,” the ranger said. “You didn’t happen to get this fella’s name, did ya?”

The West

We could see the dark billowing smoke from miles away. It was dark like a petroleum fire and unsettling because we hadn’t seen another car for hours. We were on the way from Fort Stockton, Texas to Carlsbad, New Mexico. But there was only one way to our destination and that was straight.

We slowed as we came up to the burning abandoned building, with smoke so dense you couldn’t see through to the other side. Covering our faces, we pushed forward and in the middle of the smoke, on the right shoulder, sat a dirty homeless man with the biggest shit grin on his face. He didn’t notice us until we were close because he was fixated on the blaze. I signaled to Weston to stop, but he blew passed me. We pulled over once the smoke was far enough in the distance.

“What if that guy needed help,” I said.

“Did you see him? That guy was fine. He didn’t need any help. That grin, chills man. There was something not right with him and I wasn’t going to stop” Weston said.

True, he was like a weird homeless specter and I felt the same way Weston did. Never going to forget that grin.

Soon, we were in Tuscon staying with a cousin, Daniel, who was finishing his master’s degree at the University of Arizona. The desert mountains were green with that short-lived spring bloom that changes the landscape. We had some wild nights with Daniel, checking out local bands while trying to talk to women. I made the mistake of grabbing a soft cactus that looked harmless. The next thing I knew, my hand felt like fire and my pocket was filled with razor blades. Tiny, microscopic barbs like fiberglass. The drink helped me ignore the pain, until I had to use the bathroom. When I came back, Weston had vanished.

“Daniel, where did he go?” I asked.

“Saw him leaving with some girl. Don’t worry. He will be fine,” Daniel said. “She is one of my friends.”

At the end of the night, after taking a cab, there was Weston sitting in front of the garage door with at least five empty packages of Skittles around him. “She wanted me to go home with her. I wanted Skittles,” he said.

We tumbled into the house laughing. The trip really had come full circle and was now light and easy and fun. We had about three months left to get back to Minnesota and we were committed to making it the best time of our lives. And because it was easy, time and memories all started to blend into each other, like the muddled countryside that blurred as we sped past.

The stepdad of Weston’s friend lived in Apache Junction, and he took us “Jeeping” in the Superstitious Mountains and borrowed us his pistol when we headed up to Sedona and Flagstaff to fend off any cougars we might cross. He also gave us some advice.

“When you are in a sandstorm, pull way, way off the road because the big rigs won’t see you when they make emergency stops,” he said. “Best to stay clear of sandstorms altogether.”

But we were still fools and didn’t the heed wisdom at first. From the edge of the observation deck of Meteor Crater, an impact site created some 50,000 years ago when mammoths and giant ground sloths roamed the area, we could see a massive sandstorm in the distance. Being from the Midwest, we were accustomed to tornadoes, but this was ominous in its size. After studying the crater and contemplating the heavens, we thought it was safe to push forward to Winslow as the storm appeared to be dissipating.

We were wrong and before we knew it there was zero visibility and we pulled off, covering every inch of flesh and hunkering behind the bikes using our backs to push against the gusts of wind that threatened to topple the motorcycles. Big rigs swayed in the wind as they barreled past. The storm lasted for about 30 minutes and did a number on our paint.

From Winslow, we rode south through the mountains after word came that the authorities had reopened the highway after a snowstorm. It was so cold that every 15 minutes we had to stop and hug our engines to warm our hands.

After returning the pistol, we road from Phoenix to Los Angeles via San Diego, the single longest day of riding we experienced on our small cruisers. But we were finally in magical California and it was plentiful.

There and Back Again

Weston hadn’t seen his friend for a couple years when we met up with her in Dana Point. She was doing some sort of work out there, but it wasn’t clear. Weston remembered her as a sweet innocent girl in high school who was now covered with tattoos and piercings. One morning after a house party, we had to break into her apartment after she informed us that she was kicked out of by her roommates earlier that week. All of our gear was in that apartment, so I hoisted Weston over a brick wall, and he slid through an open window.

We hopped in her car and went to Venice Beach to look at freaks before she had to meet someone at their house in Bel-Air. She went into that house and stayed for hours as we slept in the car. When she finally came back, she was high as a kite and drove back to Dana Point at over 100 mph. We had to keep her from nodding off and held on for dear life. When a car in front of us blew a tire, Weston helped her with the wheel. And then he took over driving as we yelled at her. She never told us what she was on, but it was clear it was heroin. The next day we left without a goodbye.

Now, Weston is a good-looking guy. Far better looking than myself. And while I had always been jealous of him for that, I flipped the script in Santa Barbara, our last destination before going up the 1.

Money was pretty tight, but we needed a drink, so we went to a tequila bar on a Monday night. This large middle-aged man took a liking to Weston, moving his stool close to him at the bar. He bought us shot after shot.

“This dude is hitting on you, bro,” I said, when the guy went to the bathroom. “Work it.”

“What the hell! No he isn’t. He just friendly, buying us drinks,” Weston said.

A few shots later I looked over and watched the guy put his hand on Weston’s thigh and burst out laughing, almost falling out of my chair. Weston flipped, shoving the dude off his stool.

“I AM NOT GAY!” Weston yelled.

“I am sorry. I thought it was cool. Here, one more round,” the guy said.

We were drinking top shelf tequila, and the guy easy spent $250 trying to seduce Weston.

“I think I shall be your pimp from now on, Weston,” I said back in the tent.

Every motorcyclist owes it to themselves to ride the 1. The vast Pacific to one side, and the end of America on the other. The terminus of manifest destiny. A rugged, beautiful shoreline with smooth roads. The only time I “crashed” was on the Pacific Coast Highway, when taking a slow left hander down into a parking lot at Limekiln State Park. I was trapped under the motorcycle and Weston, typically oblivious to what is behind him, took a good 10 minutes before turning around and rescuing me as I expected to get hit by a distracted driver.

After Monterey Bay and San Francisco, we doubled back to check out the Giant Sequoias and Redwoods in Kings Canyon, before staying with a friend that was working in Yosemite. There, we hiked to the top of Yosemite Falls and marveled at Half Dome and went rock climbing on a short beginners’ trail near El Capitan.

Later that night, our friend invited us to a drag party and potluck. Weston and I both have no memory of the night, but I awoke on the couch wearing a scarf and Weston was on the floor, in a dress. He did a double take before asking me what happened.

“Weston, if I knew, I would tell you,” I said.

From Yosemite, we made a pretty straight shot up to Seattle where we were supposed to stay with friends. On the way up, we tried to ride up Mount Shasta, but the road was closed halfway. We braved the cold and made it up to Crater Lake National Park in Oregon and then headed for the coast, were we camped in soggy rainforests miles up from the Pacific.

When we got to Seattle, we realized we were there a week ahead of schedule, so we decided to kill some time in Vancouver. The Canadians had different ideas and we were pulled aside at the border crossing and interrogated. We had been camping in the rain for days, had duct taped our rain suite to our boots and hadn’t shaved since Tucson. The border patrol were emptying cars, inspecting for contraband.

Inside, they grilled us separately, trying to catch us in a lie.

“Why are you trying to cross into Canada? What is your most recent address? It shows you were in Canada eight months ago. Where are you staying in Vancouver? ‘Some hotel’ doesn’t cut it. Why does it show you were in Central America? What were you doing there? Do you have utility or phone bills to show us? No, a credit card doesn’t work. When did you last work? Where? Do you have relatives in Canada? Sorry, access denied.”

We pleaded with them to let us through and offered to unpack all our gear for them to inspect but still they said no. Weston had left his lights on during the interrogation and it killed the battery. On the way back to the U.S. side we had to push start the bike every 20 feet because traffic was jammed up. It was infuriating to watch hikers casually cross from Canada into the U.S. as we pushed, dropped the clutch and sputtered a few feet forward before the engine died. The U.S. side wanted to talk to us before letting us go.

“You two don’t have criminal records, do you? Hmmm. Was it a short woman you talked to on their side? Sorry guys, she makes our life a nightmare. Get some documents and maybe try again.”

I was willing to forgive the Canadians until a few years later when I was flying to Mumbai, India, via Toronto and they pulled me out of immigration to interrogate me. While they eventually let me board my plane last minute, they informed me I was permanently red flagged.

After the border fiasco, we camped near Mount Baker across the street from a summer cabin. It was still raining, and I accidently popped Weston’s inflatable mattress. The next day the bikes were stuck in the mud.

“Just go for it,” Weston said.

I spun the tire and broke free. When I looked back, he was covered from head to toe in mud and furious. We found a hose at a gas station and I washed him off and he said he would never forgive me.

The last major pilgrimage we had to make was finding our dad’s house along the Columbia Gorge. He had lived there in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s while working at a paper mill and going to school for boatbuilding. He owned a horse and a dog named Damascus and never planned on moving back to Minnesota. Out of all the places he had been, Washington was the one he talked about the most. He almost married there, but luckily didn’t. We couldn’t find the house and he couldn’t remember the address, he claimed.

From Washington we crossed into Idaho and then Montana, getting snowed out of Glacier National Park and the Going-to-the-Sun Road.

We checked our bank accounts and there was nothing left besides enough for one last set of tires. So, we charged back to Minnesota thinking we could make it in a couple days. It was still too early in the year to visit Yellowstone.

Across Montana we adopted a steady 100mph pace. We were near Billings, Montana when we saw a woman trying to wrangle up her dogs in the ditch. Before we knew it, one of the dogs was charging us. I slowed to 60mph and watched its neck fold beneath my front wheel as I braced to lose control. We stopped and the woman clutched her dog, whose neck had been snapped in two. We helped her load the dead dog in her truck and off she went to town as her mother came out to see what was going on.

“Oh, hell. The dog is dead. Serves her right for never taking care of him. Don’t feel bad. You want to come inside and smoke a bowl? I got some weed,” she said with a toothless smile.

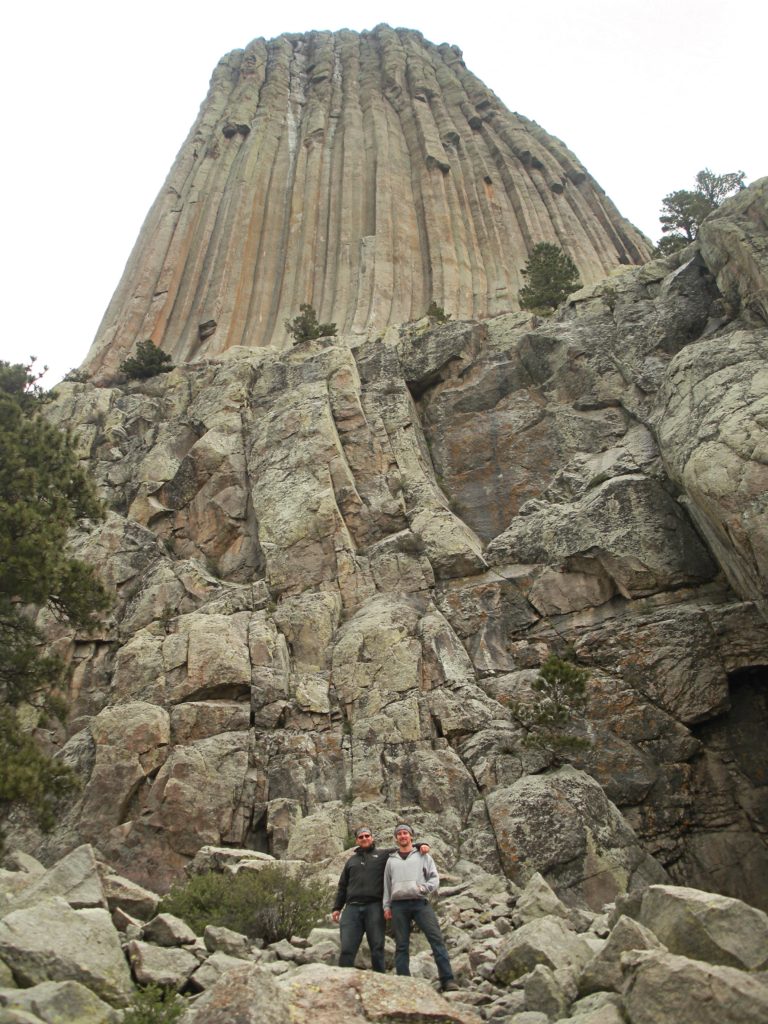

We rode the Black Hills in South Dakota and then took the mind-numbing drive across the state, with our final camping spot of the trip in the rugged austere Badlands. In Sioux Falls, South Dakota, we loaded up on fireworks and mini-American flags.

The plan was to rig our bikes near our parents’ house, light them and come storming into the driveway. We still hadn’t told them when we planned to arrive.

Our parents came out to the sound of Roman Candles exploding. It was a warm spring day, and the grass was green and vibrant. We hugged our parents and played with the dogs. It was complete. 23,000 miles across the U.S. to prove to ourselves we could do it. That there really is nothing in life to be afraid of as long as you have an adventurous spirit–and a motorcycle.