Great things often come in small packages, and that saying rings true with the Bluegrass Motorcycle Museum in Hartford, Kentucky. What the museum lacks in square footage it makes up for in quality motorcycles and memorabilia.

Additionally, visitors experience personal tours of the place from a knowledgeable guide named Jack “Hombre” Embry. Embry has been the museum’s curator since its opening in 1996, operating it with his wife, Nancy.

After passing through the museum’s front door, we saw a bike we’d never seen before. Embry said it’s a 1902 Hafelfinger, but we had never heard of such a motorcycle. Find out what we learned about this machine in the sidebar below.

The next bike was a 1906 Indian. If you would like to know what Hafelfinger’s prototype bikes looked like, just look at this Indian. It was fabulously restored in the late 1990s and looks as if it rolled out of the factory a year or two ago. It uses a kerosene-fueled headlamp for lighting, while other motorcycles of that era used propane or carbide.

I had assumed that all the motorcycles of this era were likely to have their spark provided by a magneto, but I was mistaken. Some used a tube-shaped, dry-cell battery that fed that coil, but these systems had no generator or alternator, so riders could only go as far as the battery would last before it needed to be replaced with a new one. Since the type of battery that they came stock with is no longer available, restorers instead place four D-cell batteries in the tube like you would use for a large flashlight.

Next in line was a 1911 Yale, which was manufactured in Toledo, Ohio. The one in this collection had only three owners in its lifetime, and it came with its original title. It is an unrestored example in wonderful condition.

Sitting close to the Yale is a 1915 Shaw, produced in Galsburg, Kansas. Embry traded a basket-case 1935 Harley to obtain the Shaw, a motor-bicycle that sports wooden rims held to the hub with wire spokes. Wooden motorcycle rims are a rarity indeed, and Embry said that anytime he takes the Shaw out for a spin, the fear of breaking one of its wheels looms over him.

Take note that there was also a Shaw motorcycle made in England that may or may not have been connected to the American Shaw Motorcycle Company. We do know that at one point, the English manufacturer was buying engines from the American manufacturer, so a relationship of some sort existed between the two.

Another fascinating motorcycle in the collection is a 1912 Eagle manufactured in Brocton, Massachusetts. It’s powered by a 1,000cc V-Twin made by the Spacke Machine Company of Indianapolis, Indiana, claimed to produce 9 hp. The Eagle had a production run from 1910 to 1915, and less than eight have survived the 100-plus years since they rolled out of the Eagle factory.

In addition to the wonderful collection of awesome and very rare motorcycles, the Bluegrass Motorcycle Museum is also chock-full of cool memorabilia. Embry showed me a sweater from the Two Tired Motorcycle Club of Loraine, Ohio.

The club was founded in the 1930s, but the Loraine Ohio Chapter got its start in 1940. The sweater was donated to the museum by Peter Christianson, a Danish-American man with a thick accent who raced as an amateur during the early 1940s. He had two club sweaters. The second one was from the Two Tired Too Motorcycle Club, a women’s auxiliary branch of the Two Tired Club. It belonged to Christianson’s late wife, and he could not bear to part with it.

Christianson told Embry that when he was racing in the 1940s, many events offered things like tires, chains, and other parts and accessories as prizes in lieu of trophies. Later, Embry spotted a trophy displayed at Christianson’s house and said, “What’s the deal? I thought you did not care about trophies?”

The former Two Tired Motorcycle Club member answered, “My wife kept that one because I gave it to her when we first met. I would never think of getting rid of it now.” Christianson didn’t care about trophies, but he sure as heck cared about his wife.

A visit to the Bluegrass Motorcycle Museum will likely only take a couple of hours of your time. You will love the scenic ride down U.S. Route 231, which takes you through some beautiful countryside. The road is smooth and sparsely traveled, so you can relax and take in the scenery. Tours of the museum are done by appointment only, and you can reach Jack and Nancy Embry at 270-298-7764 to book one.

SIDEBAR: What’s a Hafelfinger?

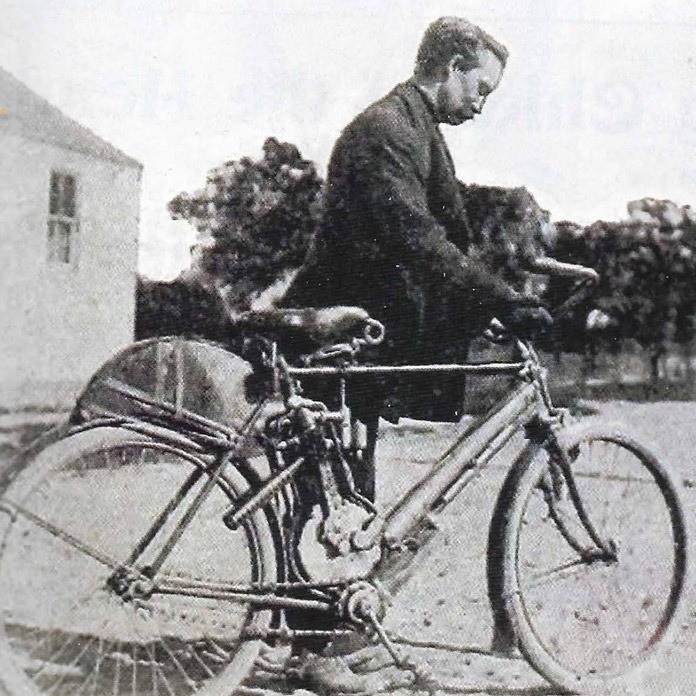

After an abundance of research, I am still not sure that a 1902 Hafelfinger ever existed, at least not as a production motorcycle. The Hafelfinger Motor Bicycle Company was founded by American-born inventor/musician Emil Hafelfinger, who was also a bicycle repairman. In 1901 he received a U.S. patent for a motorcycle with a crescent-shaped fuel tank on top of the rear fender, a so-called camelback.

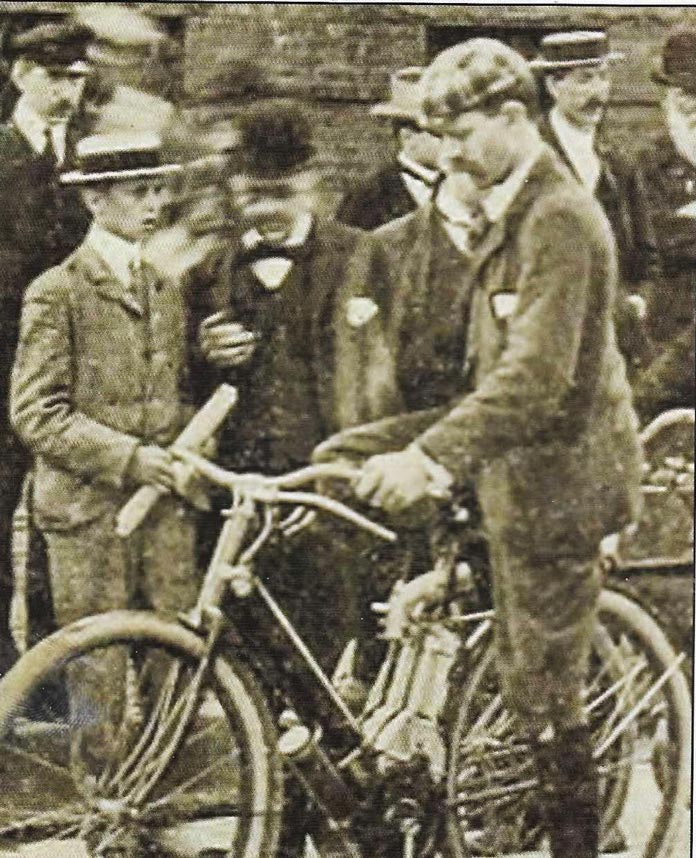

Hafelfinger built engines that could be installed on bicycles, like Whizzer motorcycle kits. Many sources insist that Hafelfinger never produced a complete motorcycle badged with the Hafelfinger name. However, Bicycling World & Motorcycle Review magazine ran a photo of Paul Hagenow standing beside his “1904 Hafelfinger,” along with a claim that Hagenow had accumulated 15,000 trouble-free miles on the bike by 1907.

This is a bit puzzling though, since Hafelfinger had, according to official records, gone into a partnership with Charles Persons and Will Pitman in 1901, and the Hafelfinger Motor Bicycle Company had changed its name to Royal Motor Works. This company would go on to produce the Royal Pioneer in 1909.

It should also be noted that the “motor-bicycle” in the old photo doesn’t seem to have the Hafelfinger name imprinted on it anywhere. Granted, there are records of Hafelfinger entering his machines in various endurance contests, races, and shows, but it is my opinion that those machines were built to showcase Hafelfinger’s engines more than anything else. Sure, there is a chance that a cycle or two built by Emil wore a badge with his name on it and were sold to the general public. There is not, however, enough evidence to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt.

When Hafelfinger showed his patented machine at Madison Square Garden during a New York City bike show, motor-bicycle companies like Pope, Marsh, Thomas, and Indian took notice of Hafelfinger’s design. They were impressed enough to ignore Hafelfinger’s patent rights and adopt them as their own. The American camelback was later employed by Indian Motorcycle.

One could argue that there never was a 1902 production motorbike manufactured under the name of the Hafelfinger Motor Bicycle Company, but what cannot be disputed is that the Hafelfinger at the Bluegrass Motorcycle Museum is a very sweet creation. It uses an original Hafelfinger engine that Embry found in Colorado 20 years ago, and most of the remainder of the bike is made up of motorcycle parts circa 1901 to 1904 (the carburetor is a 1904 Schebler) or handmade by Embry and various associates of his. It took a decade to complete the project.

Embry did not attempt to make his Hafelfinger look like a stock from-the-factory motorcycle. Instead, he built it to resemble a highly modified race machine, ready to compete on the early 20th-century American boardtracks. Perhaps the motorcycle could be called a fantasy piece. Whatever you want to call it, the machine is beautiful. The paint and chrome plating are first-rate, and it truly is a two-wheeled piece of artwork.

SIDEBAR: More to See in Kentucky

If you’re in the area, there are two other places of interest that you might want to visit. The historic Talbott Tavern and Inn in Bardstown, Kentucky, is less than a 90-minute ride north from the BMM, and the National Corvette Museum is a 45-minute ride southeast to Bowling Green, Kentucky.

The Talbott Tavern and Inn was originally built in 1779 and has great food and rooms that are much more luxurious (and far more interesting) than your average Motel 6. Jesse James (the Confederate raider, not the guy from West Coast Choppers) supposedly stayed in what is now known as “The Jesse James Room” and allegedly shot several holes in the wall that can still be seen today. One of Mr. James’ cap-and-ball pistols is on display outside the room. I think if the members of the James Gang were alive today, most would be bikers.

Rooms are reasonably priced, from about $80 to $117 for Jesse’s room. There is no extra charge for any ghost experience that might come your way. Waitresses told us tales of hamburgers flying off trays for no explainable reason and receipt slips blowing through the air when there was no draft. When we were there, Becky and I heard footsteps coming up behind us in the room where the old bar is even though we were the only two there.

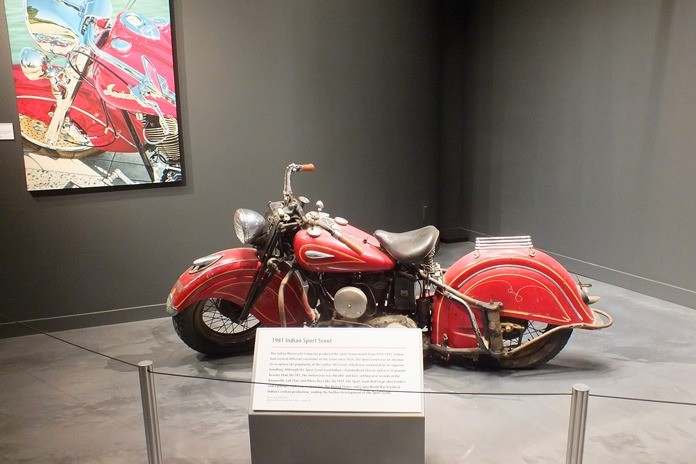

The National Corvette Museum had an American motorcycle display tucked away in one of its rooms, consisting of a nice little collection of motorcycle artwork and a 1941 Indian Sport Scout loaned to the museum by Mike Wolfe of American Pickers fame. The museum is located at 350 Corvette Drive in Bowling Green, Kentucky.