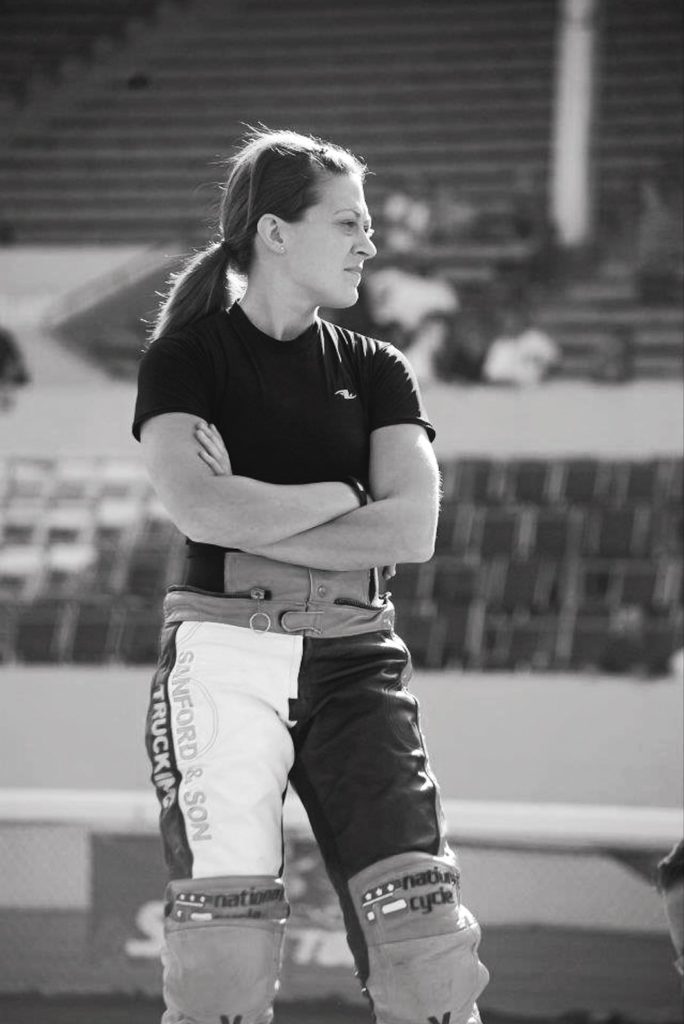

Rider, racer, race promoter, champion’s wife and now mom, Nichole Cheza Mees is a do-it-all whirlwind, and arguably the most talented woman ever in professional flat track’s premier class

Words by Joy Burgess

Photos by Mitch Friedman, Dave Hoenig, Jodi Johnson, Tom Stein, and Nicole Mees archives

We’ve written a lot about women in motorcycling over the last few months, especially women in racing: Shayna Texter, Sandriana Shipman, Michelle Disalvo, Leah Tokelove, Kayla Yaakov, Tammy Kirk and Diane Cox.

But there’s one woman racer we haven’t discussed much at all, and that’s hugely ironic given that she’s arguably the most accomplished female professional motorcycle racer ever.

Her name? Nichole Cheza Mees. And it’s entirely possible you’ve never heard her story, which is why we figured we needed to set the record straight.

In prestigious AMA Superbike – or even World Superbike or MotoGP – racing, there’s never been a serious female contender. In world-class AMA pro motocross and Supercross, Ashely Fiolek took home a handful of points in the 250cc division, but it hasn’t happened in the premier 450cc class – and likely never will.

And then there’s professional flat track racing. Six women have held national numbers, and only four have ever earned Grand National points. While Shayna Texter holds the record as the winningest Singles rider ever, no woman has ever done what Nichole did racing twins in the premier class against the best flat track racers in the world.

Cheza Mees made 32 main events, finished 20th overall in her final season among the best dirt trackers in the world, and once beat the fastest boys in the land in a Dash for Cash sprint at the Springfield Mile. And all on the ferocious Harley-Davidson XR750, the gnarliest, nastiest racebike in the land for over four decades. Many of the best riders in the world were challenged over the years trying to tame the XR, but despite being just 5’1” and 125 pounds, Nichole did just that.

While friends describe her as one of the nicest people you’ll ever meet, and her husband – five-time Grand National Champion Jared Mees – talks about what a thoughtful, caring person she is, the woman is an absolute beast on the racetrack. American Flat Track announcer and flat track historian Scottie Deubler calls her something else. “She’s just a badass,” he says, “determined and dedicated. I’m a huge fan. She raced in the Premier class and ran right there with the guys. She rode hard. She’d shine at the tough tracks. And she was always someone you had to deal with if she was out there racing – a true contender.”

A badass. A beast. And perhaps – among female motorcycle racers – even the GOAT.

But it was never about being good for a woman. According to Nichole, “I just wanted to be the best of the best, not just the best of the women.”

Born to Race

Born in 1987 in Flint, Michigan, Nichole Cheza Mees was born three-and-a-half months prematurely (just 2 pounds 9 ounces) and spent several months in Neonatal Intensive Care. “At the time,” Nichole mentioned, “the doctors were concerned I’d grow up with some severe medical issues. But I started out as a miracle baby, and I’ve never given up since!”

She grew up in a racing family; competition was in her blood. “My dad grew up racing motocross,” she said, “along with all of his brothers. After I was born we’d go racing and trail riding, and I’ve had an interest in racing from a young age. When I was three my dad got me a PW50 for Christmas. We’d opened all our presents and were playing with our new gifts, and my dad said, ‘Hey, I have one more thing for you, but you have to come outside.’ There in the garage with a sheet over it and a bow was that PW. I don’t remember any of the other gifts I got that day, but I remember the bike and immediately wanting to go ride it, and my dad took me ice riding the next day.”

That PW50 was where it all started, and as a child she was out on the ice riding with none other than the GOAT – nine-time Grand National Champion and Motorsports Hall of Famer Scott Parker. “I remember ice riding with Scott Parker. He was on a XR750 and I was on my PW50, and that’s where my roots started. Then I started riding in my yard and went to the track, practicing on the kid’s track.”

At the age of five, she raced amateur nationals for the first time on a borrowed Cobra 50. “I just jumped out there and raced,” Nichole remembered, “and I did really well. My dad told me if I fell down I should just lay there and play possum so they’d stop the race for me.”

But that wasn’t her style. “I went out and was leading the race,” she continued, “and sure enough, I fell down. But I jumped up and kept going. My dad asked me why I didn’t just lay there and get a red flag. But I just wanted to race.”

After that taste of racing as a young girl, she raced both motocross and flat track for some time. Once she got into the 85s and 125s she had motorcycles set up for both styles of racing, and her dad told her it was time to make a decision: flat track or motocross. “I was doing really well in flat track,” Nichole said, “and I loved the adrenaline rush. In motocross, they had a women’s class. While we didn’t have to race in the women’s class, it was expected that we would, although I also raced with the boys. In flat track I just raced the guys. There was no separation and no different class. I just wanted to be the best of the best, not the best of the women, so that made me decide to go with flat track.”

Once the decision was made she did well as a racer through her early teen years, placing on the podium in flat track races and in ice racing during the winter months. Through her early racing career, she’d win amateur national championships in both flat track and ice racing.

“Growing up in Michigan,” Nichole told us, “we always had an ice season, and I rode on the ice my entire life. It’s always been one of my favorite times to go riding. There was no pressure. We’d just go to the lake all day long and run tankfuls of gas through the bikes over and over again. The cool thing about ice racing is that you get a ton of traction because we put studs in the tires. We could do oval tracks and TT style tracks (without a jump), and we’d make courses a mile long or more, go out and ride, and have a great time.”

“At the dirt track,” she continued, “you’re always in serious competition mode. I have a soft side, but I had to have that ‘ready-to-go’ mode at the track. There, you’re either in race mode or job mode. You’re there to perform and you’re out there making sponsors happy and showing fans what you can do. It’s a job, and when you go to your job it’s not always fun and games. Sometimes you have a great time and sometimes you have a day you don’t want to think about for 10 years. But ice riding was really fun. And while I didn’t like it better than flat track, it was a more fun time for me during my career.”

As a teenager, racing meant she had an intense schedule, juggling both school and time at the track. “I missed a lot of Fridays at school to go racing,” she says, “but the rule was I had to have good grades. And I had to go to school when I got back from the races, no matter what time we got back. Some days we’d pull in at 6 am Monday morning, I’d shower and go to school. That’s what I had to do if I wanted to race.”

Her dedication to racing and her success winning championships in both ice racing and flat track racing grabbed the attention of the American Motorcyclist Association. And in 2003, she won AMA Female Rider of the Year in a stacked field of females from motocross, ATV and other types of racing. It was a big moment for her, and a foreshadowing of what the future held for her as a racer.

Taming the V-Twin Beast

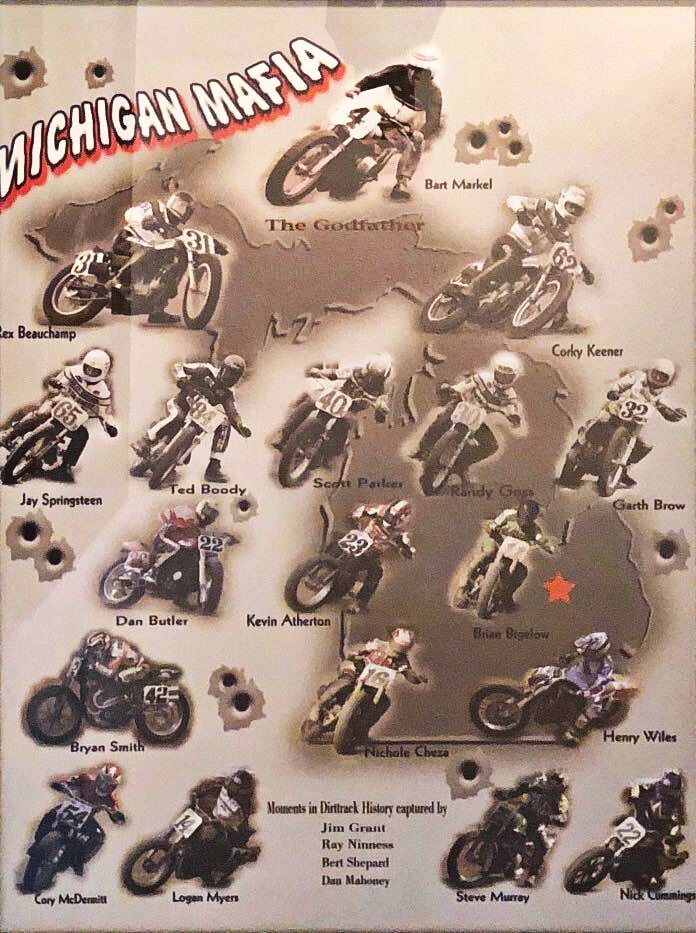

Growing up in Flint, Michigan, an area known for spawning some of the biggest flat track racers of all time, Nichole was heavily influenced by members of what’s known as the ‘Michigan Mafia.’ Legendary 1960s racer Bart Markel (The Godfather) was key to the formation of the group, and although it wasn’t a formal team, the moniker was given to the many talented riders from the Flint area. From the 1960s to the early 2000s, if you went to a flat track race, you’d usually find a Michigan rider out there on the track…and there was a good chance you’d get beaten by one of the Michigan Mafia, too. Guys like nine-time Grand National Champion Scott Parker, three-time Grand National Champ Jay ‘Springer’ Springsteen, and flat track legend Kevin Atherton were just a few of the guys she grew up around. And eventually, Nichole, along with current AFT riders Bryan Smith and Henry Wiles, became a part of that Michigan Mafia themselves.

“I watched people like Parker, Springsteen and Kenny Coolbeth growing up,” Nichole mentioned, “and as a kid, I don’t think it ever crossed my mind that I’d go flat track racing professionally. But as time passed I thought maybe I could go professional and do this thing. I could ask them for advice, and when I started to get into the pro ranks and began riding big bikes, they were a great resource for me. And they saw I had some potential.”

But while riding a 450 flat tracker is one thing, jumping aboard a Harley-Davidson XR750 V-twin and wrangling that heavier bike at speeds of up to 130 mph is another level of racing altogether. Even full-grown men often struggle with the transition to the bigger, heavier twins.

“I think the biggest challenge when you go from a 450 to a twin,” noted Chris Carr – seven-time Grand National Champion and former fastest man on two wheels – “is first the weight, and second, that newer twins are starting to get a bit taller. The shorter you are [and remember Nichole is only 5’1” — Ed.] the harder it is to maintain proper leverage when you’re leaned over in the corners and wrestling a bike that’s now 90 pounds heavier than what you used to ride. It definitely helps to have leverage and upper body strength. If I compared Nichole to current Singles rider Shayna Texter, Nichole has a tiny bit of a height advantage and more upper body strength. And if they raced each other, you’d see that advantage. When you have to get physical, that leverage and that extra strength pays dividends.”

But while some racers struggled with the transition from 450s to twins, Nichole excelled. AFT announcer Scottie Deubler says this: “You can’t just throw twins around like a 450, but Nichole could handle the XR750 just as good as the guys could, and she kept going to the gym so she could be competitive with the boys.”

Husband and five-time Grand National Champion Jared Mees echoes that. “Nichole was really strong, especially for a female. It’s easier to ride a 450 single, but she jumped on the twin, she excelled at it, and she did an outstanding job.”

One thing Nichole had going for her was the chance to jump on a twin at a young age. “I was very fortunate to get on a twin very early in my career,” she said, “and few racers (not to mention females) get to do that. I got to ride a twin in Ohio in some of the pro classes when I was just 15, and then I went to Canada to race full-on championships on the twin that year.”

“I knew I wasn’t as strong as some of the guys I was competing against,” Nichole continued, “so I was in the gym and lifting weights every day. I did a lot of endurance training, bicycling and running. I was always riding my motorcycle to keep my skills sharp. I knew my biggest disadvantage was strength, so I was diligent about training and building muscle in the off-season, then maintaining it during the racing season. I put in a lot more work than some of the guys out there, and I enjoyed that part of it.”

All that hard work and training paid off, and on 07-07-07 Nichole made her first Main Event at the Joliet Half-Mile in Illinois, and did it in spectacular form by beating out another flat track legend, 2000 Grand National Champion ‘Smokin’ Joe Kopp. “I had to go to the last chance qualifier,” Nichole remembered, “and then Joe Kopp was in my Semi Final. At the time you had to get first and second to transfer, and I knew I had tough competition racing Joe. But I got the holeshot and led the entire time. I remember my last lap was intense because I didn’t know how close the guys behind me were, and the nerves sorta got me on that last lap. And that was an awesome moment for me to make my first Main Event and earn my Grand National Number in the Premier class.”

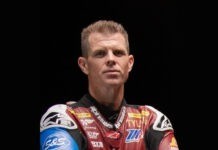

Through her years as a pro racer she made 32 Main Events and had some excellent top-10 finishes along the way. In 2011 she pulled off the best finish a female racer has ever had in the Premier GNC class, and Chris Carr just happened to be racing alongside her at the time.

“To this day,” Carr said, “she’s had the best finish ever for a female – seventh place at Knoxville, Iowa on September 10, 2011. I finished right behind her in eighth place that night; the one time in my career I got beat by a girl. She was a very accomplished racer. I think she did really well and paved the way a bit for someone like Shayna Texter to come along. She proved to the world that a woman could contend in one of the toughest sports to compete in against the men. She set a standard for the women coming along behind her. I couldn’t figure out how to pass her that night. She could turn the throttle, and she did a great job.”

[Ironically, that weekend was extra special for Texter, too, who won her first National – becoming the first female to win an AMA National – by beating current fiancé Briar Bauman in the Singles Main event. Ed.]

Unfortunately, while Nichole was breaking records for women, professional dirt track racing was in the doldrums. Not much money, not much outside sponsorship, and not much clear direction, either. “She was in the sport when it was at its ultimate low for visibility and sponsorship,” says husband Jared. “She’d do what people called the ‘Nichole shindig’ – a party held at Scott Parker’s bar to raise money to go racing. When that money ran out she was pulling money out of her own pocket and trying to team up with other riders to reduce costs. She went racing on a very small budget and did what she could with what she had.”

One of the frustrations of racing on a tight budget is equipment failure. “She had a lot of races where she was doing so good, and then the bike would break,” Jared says. “She probably missed 10 main events due to the bike breaking or a flat tire. She had some rough luck on her side but still had some really good runs in the series.”

In 2014, Nichole ended up teaming with Harley-Davidson with some help from Terry Rymer and Black Hills Harley-Davidson. “Nichole had an opportunity to get funded by Harley-Davidson,” Rymer told us, “and the only way they could do that was to line her up with a dealer. She called me at Black Hills Harley and I agreed. I loved the opportunity of doing that and having an XR750 from Black Hills out there with her on it. We threw in some money, H-D threw in some money, and we got a plan together to go racing.”

“What stands out about Nichole,” Rymer adds, “is her tenacity and refusal to give up. She worked hard, put in the effort with training, and presented herself well. That’s what makes you want to get behind someone. She was always such a fan favorite in the pits – everyone just loves her, and she was into racing whole-heartedly, no matter what. I used to show up, help her out and clean her leathers for her, and [current Singles rider] Shayna Texter said, ‘Geez, how do I get a sponsor like that?’ [Laughs]”

Her very last race was in 2015 at Delmar, Delaware, and it didn’t end the way she’d planned. “I had a bad crash there,” Nichole told us, “and that kind of ended my last season. I was having such an awesome season, but I broke my eye socket in that crash, losing my vision for some time until they could repair it. Out of all the crashes I’ve had, that one made me think that maybe I wanted to step back from racing. Broken bones in the past didn’t scare me away, but when you lose a major sense like that, you realize ‘whoa, I’ve got a lot to lose here.’”

A Flat Track Love Story

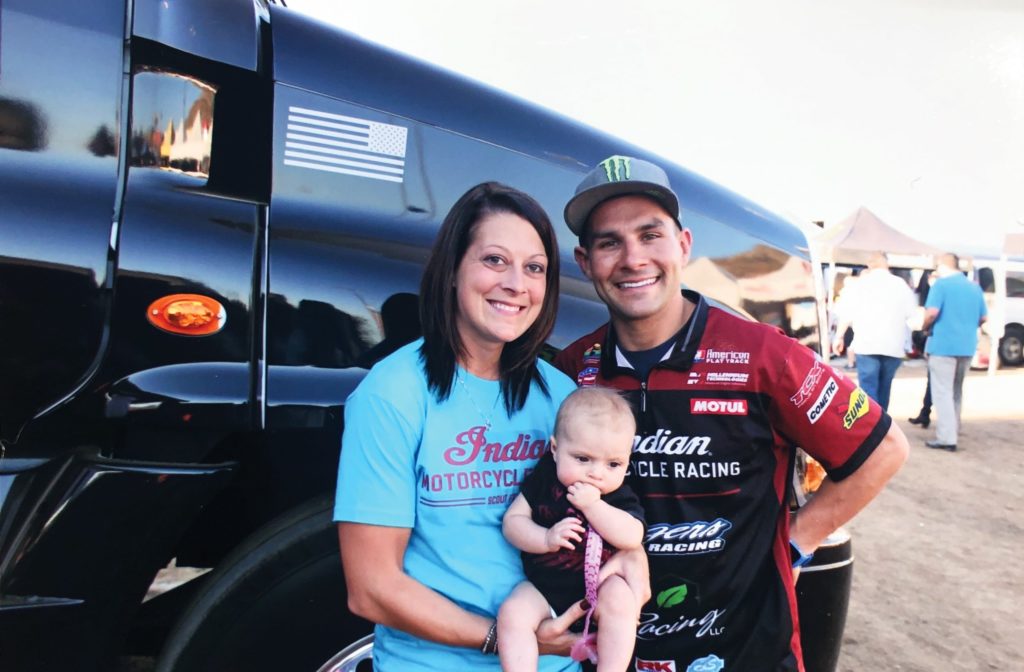

As much time as Nichole spent in the dirt as a kid and young adult, it’s no surprise that’s where she found love, too. While she and now-husband Jared Mees lived in different parts of the country, they saw each other from time to time at the Amateur Nationals that took place at tracks like Springfield. “I was the shy kid,” Nichole said, “and I wasn’t the person who would walk up and start a conversion. I’d walk by, and Jared’s dad was a big burly guy, so I wouldn’t go over into Jared’s pits.”

“When I was 14 or so,” she continued, “we went to a race at Laconia. They did a Dash for Cash and took the three fastest pros and the three fastest amateurs for the dash. I didn’t get a great start, but I passed Jared! He later said when I passed him that he was hoping I’d pass everyone else, too. That was the first time we hung out. I asked for one of his posters that night, and he had me come over to his box truck and asked if I’d like him to sign it. After signing it, he handed it to me and kissed me. I was in so much shock I didn’t even say anything to him! I just walked away [laughs]. But that’s where it all started.”

For a long time the two said they were just friends. “We were sorta afraid to say we were a couple,” Nichole remembered. “Would people take us serious in racing if we were dating? One Christmas he and one of his buddies drove all night, spent the day with me, and then drove home all night. My dad said, ‘I thought you were just friends? No friend drives all night to see somebody!’ But once we established that we were competitive, then we told everyone.”

The Springfield Mile – the spot where Nichole beat the best of the best in the Dash for Cash – has always been a special spot for the two. “Jared proposed to me right in front of the fans at the Springfield Mile in 2012,” Nichole mentioned. “They asked me to be a part of opening ceremonies, and I thought Jared had been acting weird, but I didn’t think anything of it. I went up for opening ceremonies, and he proposed to me right there. I thought, ‘Is he for real?’ He was always the guy who said he wasn’t getting married or having kids. I actually said into the mic, ‘Are you serious right now?’ He asked, ‘Is that a yes?’”

AFT Announcer Scottie Deubler did the honors. “Everyone was kinda nervous,” Deubler said. “We didn’t have much of a rehearsal, but she put on a dress, Jared changed, we had a short ceremony, and they cruised off on Jared’s #1 XR750 around that mile track.”

Motherhood: A New Challenge

A few years later on May 24, 2017, just four days before the Springfield Mile I, a little girl joined the Mees family. And the birth of Hayden – named in honor of the late Nicky Hayden and his family – changed Nichole’s life. “Parenthood kinda changes you,” she said. “The year I found out I was pregnant was the year that we lost two racers. I just found out I was pregnant and I thought ‘OMG, do I really want Jared to race anymore?’ I could be a single mom in just a second. We know those risks are there; we’ve known it our entire lives. But it’s been more prevalent in the last five years.”

She wasn’t the only one seeing things differently as a parent. “I remember the first time I went riding after I had Hayden,” Nichole laughs. “Jared was like, ‘Whoa, are you sure you’re going riding? Do you have the right equipment? You won’t go out there and really go for it, right?’ He was concerned. But I told him I was pretty sure I could handle it. But it does make you both think twice and change your mindset a bit.”

Nichole and Jared are the promoters of the Lima Half-Mile race in the American Flat Track series, and Nichole was out there taking charge just three weeks after Hayden was born. “Three weeks after I had Hayden,” she told us, “we promoted that event and Jared was racing that day. I just had to hand my child off and deal with it, working all day taking care of ticket sales, vendors and all the things that go on behind the scenes. Being a new mom and passing my baby off to others while dealing with Lima was tough, but I had people I love helping with her. I made it through a 15-hour day with a newborn while breastfeeding, and I just thought if I could handle that, I could do anything.”

Motherhood was definitely a new challenge for Nichole. “I stepped back and took on the mom role,” she said, “and while I love every moment of it, it was a struggle at first because my lifestyle changed so much. I was used to being on the go, training and racing. In one year everything stopped. I stopped teaching [Nichole has a BA in Elementary Education and a MA in Special Education], stopped racing and had a baby. At that time I wasn’t really training, I had a newborn, and I was figuring out my body again and my child. It took me a good year to adjust. I put my life on hold, but then I thought, ‘Why am I putting my life on hold.’ I figured I should be doing things I love, so I got back to working out again, we always do Lima, I travel to pretty much every race with Jared, and Hayden gets to be a part of that same lifestyle we had when we grew up.”

Of course, that lifestyle isn’t always easy. “Jared does his own program,” Nichole went on, “and spends a lot of time training and traveling and marketing himself. Sometimes he’s out on the road and has been gone weeks or even a month. That’s a lot of time being missed with Hayden, and sometimes we wonder if we’re doing the right thing.”

“She’s an outstanding mom,” Jared told us. “There are a lot of days during crunch time where I’m up and out of the house going riding and training, and I don’t get back until dinnertime. That’s hard. It’s hard on everybody, but it’s awesome that Nichole’s able to take things over and be such an awesome mom, and she also does a great job helping me with my program, especially on race day.”

“Now that Hayden’s turned three,” Nichole said, “I finally figured out what I’m supposed to do. I created a new business so I can stay home with her and still use my degrees. I’m creating a subscription box for moms (www.mommyandmees.com) with self-care items, matching items for mom and child, and then activities for moms to do with kids. I want to help women figure out they’re still human after parenthood.”

Friend and flat track photographer Jodi Johnson (known as Mrs. JJ5 around the paddock) had this to say about Nichole: “It’s been amazing to watch Nichole over the years. I’ve seen her transform from a talented racer to race wife to race promoter. But my favorite role to watch her in has been Hayden’s mom. She’s someone who has drive and passion for whatever she’s doing, and she’s one of the kindest souls you’ll ever meet. You’ll love her instantly!”

Often it’s what peers have to say about a person that’s most true and most honest – and Nichole certainly has plenty of friends that’ll speak on her behalf.

“I saw her race the best of the best,” Scottie Deubler said, “and she wasn’t scared or intimidated by anybody. I think she trained harder than most of the guys did, and she was built. She knew what she had to do to race the Harley. She always rode well on the 750 at Lima, and that’s the toughest track on the schedule to me. And she always did great at the Springfield Mile. The crowd noise when she’d pass someone was just crazy. When she made a move, the crowd was always behind her cheering her on.”

“In addition to that seventh-place finish and me following her across the finish line,” says Chris Carr with a laugh, “Nichole did herself proud in a very male-dominated sport. For that, I think we’re all very proud of what she was able to do under some tough physical circumstances. We guys never want to get beat by someone wearing pigtails, but Nichole and then later Shayna Texter…well, they have embarrassed a lot of boys and men along the way, including me, and that’s a good thing!”

All of which, of course, begs a pretty good question: What if Nichole Cheza Mees had been born a little later and was racing on the super-capable Indian FTR750 right now?

Food for thought!

Great story, well done.