Bringing a clever concept home

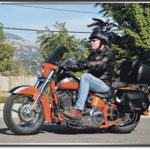

With Tour Pak affixed, the horizon’s the limit

With the introduction of the 2010 FLSTSE CVO Softail Convertible, The Motor Company not only resurrected their “convertible” concept and nomenclature which last saw usage a decade ago, they took it to a new extreme, applying the quick-change dual-personality discipline to a Softail chassis for the first time and presenting it as one of the exclusive Custom Vehicle Operations models, another first. Breaking even more new ground, the underlying platform of the CVO Convertible is a unique design, distinct from any Softail model in the Harley-Davidson core collection. As a fan of function and thus someone who rued the passing of the convertible approach from the Milwaukee design play book, I was enthused by this creation and impressed with the execution of the concept which, given the very different roles the model was being asked to fulfill, demanded a delicate balancing of custom panache and practical road chops.

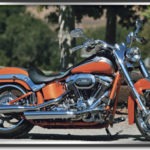

In full dress the Convertible’s windscreen, saddlebags, passenger pillion and backrest give it some authentic touring credentials. Stripped of those quick-detach components, the bike becomes a sleek custom stunner awash in chrome and eye-popping paint. The thin saddle and slammed rear suspension contribute to the bike’s dashing profile, and combine to give it a seat height of just 24.4 inches. Of all 2010 Harley models, only the new Fat Boy Lo plants the operator closer to the ground. With the detachables detached, the dazzling 18-inch, five-spoke chrome aluminum Stinger wheels and matching sprocket and rotors take on an added prominence, and the removal of the passenger pillion reveals a trio of trick rubber/chrome fender rails. The Convertible’s hind quarters hammer the custom theme home with new full-coverage rear fender, low-profile 200 series radial tire, and a super-sanitary lighting configuration that integrates all functions—running lights, brake lights, turn indicators and license illumination—in one svelte two-fixture light bar. At the heart of the matter is that elegantly-finished and granite-hued TC110B motor.

It was at the Custom Vehicle Operations model launch last summer that Jeff Smith, the CVO Convertible team manager, mentioned in passing that in addition to the stock suite of detachable gear on the model there would also be a detachable Tour Pak available as an option, one dressed in leather and buffalo hide to match the saddlebags. That piqued my interest mightily. That, I figured, would be just the thing the Convertible needed to bring it into full long-distance touring readiness. I requested a test bike equipped with the box from Harley’s Fleet Center and they were kind enough to hook me up. Hot damn.

Practically speaking, the addition of the Tour Pak resulted in a mount that might well live up to its hype as being fully capable of a comfortable fully-loaded cross-country trip to Sturgis, and once there, capable of transforming effortlessly into a real head-turner on Main Street. With that said, it remained to be seen how adept the Convertible would prove in real-world long-distance duty, the big question mark being whether or not something that slammed and glammed-out could provide reasonable ergonomics and all-day long-mile comfort.

The answer to that question came on the first day I took possession of the bike down in Carson, California, and proceeded to pound 475 miles on the odometer in seven and a half hours, carving through commute traffic in both the L.A. Basin and the San Francisco Bay Area, and spending the intervening distance hammering from fuel stop to fuel stop up the asphalt catatonia of I-5. The answer to that question was, for me, a qualified yes.

For a long-legged rider like myself, the accommodations on the Convertible are compact, owing to that skinny seat and placement of the floorboards. For those with shorter inseams (i.e., most of humanity) that’s most likely a nonissue, but it took me a number of miles to adapt to the riding position and find the sweet spot for my long bones. It helped in that regard that unlike every other FL model in Milwaukee’s stable, the Convertible dispenses with the heel shifter that restricts boot movement, and thus seating position possibilities over the multi-hour spells between gas stops. Also helping is the handsome color-matched tinted windscreen, which does an adequate job of keeping the wind off the torso allowing an upright operating posture. Considering the windscreen’s modest proportions, that’s about as much as you could reasonably ask of it.

Like every CVO creation, the Convertible is accessorized with an exhaustive list of custom components, components that are rarely there for practical purposes. It’s all about cosmetics for the most part, but I’m happy to report that the Rumble Collection of parts applied to this bike include hand grips and floorboards with sufficient rubber surfaces to give both boots and gloves a good grip and some measure of isolation from the vibration of the big solid-mount motor, which at certain engine and road speeds can be buzzy. One custom component—unique to this model—that also serves a functional purpose is the digital speedometer that displays miles per hour in big easy-to-read numerals. That’s a real boon for the far-sighted among us. Less easy to read is the tachometer surrounding the display which has a little arrow poking in from the periphery to indicate rpms. It’s also only marginally necessary with the TC110B grunting out gobs of torque across a wide range of engine speeds.

Overall, the Convertible earned high marks in the high-mile high-speed punishment exercise, but in order to meaningfully assess the packing capacity and convenience of the Tour Pak-equipped test bike as well as its suitability for the type of back-road weekend overnighter ramble duty it’s most likely to be put to in practice, a more scenic and leisurely outing was called for. A three-day excursion, one that covered a wide variety of terrain and two-lane blacktop, would be just the ticket. Out came the maps, and after some consideration I settled on a run up to Buck’s Lake at the northern end of the Sierra Nevada Crest in the Feather River Country. I reserved a couple of nights in an old log cabin with a kitchen at Buck’s Lake Lodge, enlisted My Personal Attorney, Mad Dog Esq., to ride along as wing man and set to packing.

My full kit of clothes, tools, cameras and a cooler disappeared without a fuss or hard decision into the saddlebags and TourPak. Included were the gauntlets and chaps that could prove useful at elevations above 5,000 feet in what were developing at the time of departure to be unseasonably cool conditions. I also packed all the fixings for a steak dinner at our destination. No gear had to ride on the pillion.

I said this would be a leisurely excursion, and the Convertible agreed since the bike’s chief downside as a multi-purpose mount is that, compared to Harley’s touring-dedicated and more function-minded machines, this bike has a stunted cornering clearance. That’s the glaringly obvious trade-off the model makes for its slammed custom stance, so it came as no surprise. Knowing that fact going in, I tooled pleasantly along, winding up and over the Mayacamas Mountains with no illusions about the bike’s cornering prowess. After a fast dash across the Sacramento Valley to Oroville, the Sierras loomed and again I went into the relaxed sightseer mode I tend to adopt anyway when there’s beauty to behold. The pavement on National Forest Road 119 leading up to Buck’s Lake is pure velvet and marvelously twisty, and the Convertible’s general handling manners in those conditions are downright polite, and pushing the bike to the floorboard-grinding limits of its lean angles revealed no other unwelcome deficiencies.

A couple of hundred miles later we arrived at Buck’s Lake Lodge, and discovered to our satisfaction that the place had a bar, store and restaurant. Less satisfactory was Cabin One, the 75 year-old relic of a log cabin where we’d be spending the next two nights. I have the lowest standards of cleanliness and décor in lodgings of anyone I know, with the possible exception of Mad Dog, and that attribute is actually a source of pride for the both of us. Cabin One tested our faith.

“European housekeeping” is the Lodge’s charming promotional enticement and has been since the place opened as a romantic Alpine retreat on the shores of the recently-filled Buck’s Lake reservoir back in the early ’30s when extensive hydroelectric projects were taming the wild Feather River country. I have no idea what that phrase’s original meaning was, but it currently translates to “broken, dirty and neglected.” And, at $141 a night, “overpriced.” The bounty of physical hazards offered by Cabin One, from the haphazardly patched and ankle-breakingly uneven stair steps to the hoary exposed wiring tacked to bare logs inspired attorney Mad Dog to rename the resort “Tort Mountain Lodge.”

But enough of that. We’re here to talk touring, and after a lovely night’s slumber disturbed only by Mad Dog’s apneaic impressions of taking a dull chainsaw to a chunk of reinforced concrete, and the 5 a.m. reveille furnished by the lodge owners’ lonesome chained-up hound dog, I was up and rearing.

A day of sightseeing on the back side of the Sierras from Quincy to Portola ensued, and for that laid-back gambol I’d stripped the Convertible down to its glamorous alter-ego. In so doing I put to the test Jeff Smith’s boast at the time of the model’s introduction that it could go from “a bona fide touring-capable vehicle to an extremely clean-looking custom cruiser,” and that the morphing would happen “in less than two minutes, no tools required.”

That’s mostly true, it turns out, but not entirely. After practicing the procedure and figuring out the subtleties of the docking apparatus I was able to get it down to three minutes—but since that included the Tour Pack rather than the stock passenger backrest, the two-minute figure is doubtless feasible. However, to truly complete the transformation, you also need to remove the passenger grab strap after the pillion’s removed. That takes a tool. Hah! A small Crescent works. I should also mention that while removing the saddlebags doesn’t require them to be unloaded, as a practical matter the Tour Pak does—it’s unwieldy enough empty. Putting all that stuff back on is every bit as speedy.

More importantly, unlike the old Convertible models where stripping the gear off left you with a garden variety FXR or FXD, undressing the Convertible is more like a magic act that suddenly reveals a truly arresting and mouth-watering work of Softail beauty. It’s a night-and-day transformation.

For our testing purposes here, the only information that the day of riding around the Sierra Valley region added to what we already knew came on Highway 70 heading into Portola. That stretch of road features some truly battered and deeply rutted pavement and challenged the Convertible’s short-travel rear suspension. The bike soaked up most of the rough stuff without undue jarring, but on the worst of it I took to rising out of the saddle to avoid the whack.

In terms of the Convertible’s suitability for the two-up touring purposes it will often be put to, the Tour Pak’s integrated backrest is a fat plush cushion, and in combination with the generous padding of the pillion makes for outstanding passenger accommodations. From a packing standpoint, if you’re not planning on hauling the bulky photo gear and dinner fixings I hauled, there’s adequate capacity for a light-packing couple to hit the road for multi-day stints. Also making the Convertible attractive as a Sturgis-bound custom touring mount is the bike’s fuel economy. Over the course of 1,463 miles, riding the bike in a wide variety of modes from high-speed Interstate duty to mountain tourist lollygagging produced an average fuel consumption of an impressive 42.23 mpg. The CVO Convertible lists for $27,999. The matched Tour Pak and docking hardware add another $679.90.