Unlikely lord of the long haul

Never heard of a pro-tourer? You have now.

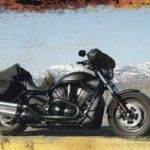

Nobody knows what this thing is, exactly. Even H-D enthusiasts are momentarily perplexed by this sinister beast with its fat rear rubber and stealth fighter styling, looking as much like a George Barris mock-up for a remake of “Road Warrior” as any V-Rod model they’re acquainted with. Untrained eyes have an even harder time of it, mistaking it for some kind of avant-garde custom creation or skunk works pro-street screamer. And then their eyebrows arch when they notice the subtle “Harley-Davidson” script on the airbox cover, followed invariably by an incredulous, “It’s a Harley?”

This machine exudes menace in the same way squint-eyed strangers in black dusters exude menace. Kick in an Ennio Morricone soundtrack and they’d be clearing the women and children from the street when I ride into town, basking in a badness-by-association inference I reinforce by refusing to smile or respond to inquisitive onlookers with anything more than mumbles, faint nods, and a mien of pure smugness like I’ve just won this bike in a fiddling contest with Old Scratch.

The Night Rod Special is the latest and most outrageous addition to the VRSC platform; the unholy fruit of an experiment in genetic meddling with recombinant V-DNA; an experiment that’s gone horribly, horribly… right. What makes the Night Rod Special special involves three basic mutations to the pre-existing VRSCD Night Rod, the first and most operationally significant being the splicing of V-Rod forward foot controls onto the machine. That change away from midmount positioning, combined with drag bars and a slammed rear suspension, alter the Special’s personality—and ergonomics—dramatically. Mutation number two is the uptick in rear tire size to the 240mm Dunlop that debuted on the 2006 Screamin’ Eagle V-Rod, and lastly and most noticeably, is the utterly unchecked use of black paint, powder coating and anodizing on the whole package. The Special is available in either Black Denim on Vivid Black, or Vivid Black on Denim Black—and you can substitute “flat” and “gloss” for those factory terms.

Ergo eccentric

In recent years there’s been a determined campaign on the part of The Motor Company to tighten up the ergonomic triangle of handlebars, seat and footpegs on virtually all their models, with the objective of tailoring the machines to reach a shorter—and thus wider—audience, most notably the distaff. The losers in that campaign have been the long riders—those over six feet tall—who’ve had to scrunch up somewhat to comport themselves to the new order. Happily, the Special missed that memo completely and went off in the other direction, setting its own defiant agenda and configuring a triangle that doesn’t just favor the tall, it demands the tall. The result is a seating position and posture unlike any other Milwaukee model, and not by a little. Even at 6-foot-4, I initially found the Special’s stretch so unfamiliar that my first impression upon mounting the machine at Harley’s Fleet Center in L.A., in preparation for a 500-mile shakedown cruise was an audible, “Uh oh.” Feet way forward, butt well back, and arms near the limit of their extension, I felt folded like a taco shell, and the possibility that this would prove a reasonable posture for long-distance riding seemed laughable. That concern was dispelled within the first 50 miles on the freeway as my body settled into the wind and I suddenly found myself perfectly situated for the draft, and remarkably, enduringly, comfortable.

I refer to that first outing on the Special as a shakedown because what I had in mind for this bike was a serious road trip from Northern California to Laughlin for the River Run, and also as part of that preparation, I’d requested that a set of bags from the P&A catalogue be installed on the Special, and what a set of bags I got. They’re designated the VRSC Sport Saddlebags and they’re outstanding both visually and functionally. They use a substantial tubular mounting bracket that matches up elegantly with the rear fender of the bike, and features quick-release docking points for the rigid-bodied ballistic nylon bags. Installed, the whole setup integrates so convincingly with the lines of the bike that it looks like a distinct V-model, and proved yet another source of consternation among baffled onlookers on the road. The capacity of the bags is exceptional, and the access effortless. A pair of zippers flanks the top flap of each, and a Velcro flap secures the end opening, and getting into a bag requires merely pulling up on the flap and peeling back the lid. Pockets on the front and side of each bag offer additional convenient storage for small items you like to keep at the ready. A whole lot of gear will go into these bags, and they have sufficient flexibility to allow stuffing in more and forcing them closed.

Talk about a Revolution

Each time I return to the test saddle of a VRSC, usually after many months of riding air-cooled V-twins of various displacements in various configurations, I get jazzed all over again by the performance properties and capabilities of the Revolution motor. And each time I have to go through a refresher learning curve, reminding myself that my ear is not a reliable judge of what’s going on in the grand mechanical scheme of things, conditioned as it is to the shift point RPMs of those others. Things are very different on the liquid-cooled, overhead-cam, 120 hp Revolution, and that difference starts with cold weather start-ups, where the high-strung motor is positively temperamental until its temperature reaches its happy place. Then the fun begins.

You can exceed any legal speed limit in first gear on this bike, or you can troll at 45 mph in fifth, but what’s really a visceral and aural kick are the three distinct stages of boost the motor manifests before the rev-limiter calls a halt to the fun at somewhere around 9000 rpm. First comes the confident—if somewhat understated—surge that takes you to about 3500 rpm. Then comes the resonant whine that sounds like high-speed barrels kicking in and the sudden burst of power that follows it in quick order, and just as quickly you’re well past the redline of any air-cooled V-twin—and resisting the impulse to shift—by the time you reach stage three. That stage takes over above 6500, where you suddenly find yourself shooting down a wormhole and ripping through the time-space continuum like an arcade game. (These rpm figures are only approximate. As handsome as the instrument cluster is on the Special, the tachometer is too small for me to read with any scientific accuracy. But you get the drift.)

Setting some limits

Having all that meaty power on tap, and feeling coolly aggressive in my taco shell bring-it-on posture, I naturally found it irresistible to get jiggy with the sportbike-spec twisties on Highways 198 and 25 between Coalinga and Hollister—the squiggliest line between where I picked the bike up and where I was going, and thus the planned squiggly test portion of our program. That’s a pretension that proved short-lived, as the first serious dive into a curve peeled my boot right off the footpeg, heel first. That tempered my attack for sure, but not my enthusiasm, since moderate speeds on these serpentine back roads have their own rewards, and any fool can take one look at the Special and conclude with some confidence that it’s not some kind of sport-tourer, bags or no bags. It’s then that I settled on the “pro-tourer” description for this bike, borrowing the vintage hot rodder term for Detroit muscle set up somewhat for real-world road duty. That would prove to be an apt term for the Special’s touring persona throughout this caper.

Off to Laughlin

With about 800 miles already under my butt by this time, I’m at home in the saddle of the Special— I’m familiar with what it does well and what it does more reluctantly, and we’re ready for whatever the open road deals out. Day one is largely a high-speed drone on multi-lane pavement, through the Bay Area, down the Central Valley, and up into the Tehachapi Mountains, but it does give me an opportunity to assess the Special’s lane- splitting prowess when Highway 58 becomes a parking lot—and a hot parking lot, at that—for mile after mile of the mountainous ascent. This also gives me an opportunity to discuss the bike’s 240mm Dunlop, and fat tires generally, and the first thing I can tell you about fat tires is they’re usually pure white-knuckled misery when splitting lanes. Especially the 300mm jobs, which treat every raised reflector as an excuse to pitch over sideways. That’s true to a lesser extent on the 240mm Metzeler and 250mm Avon, but it’s not the case at all with this Dunlop. This tire, in fact, behaves with surprising compliance under a whole lot of conditions where you wouldn’t expect that to be the case. And once you’re accustomed to having that much meat behind you, there’s not much noticeable difference between this tire and more conventionally proportioned sections in most circumstances.

Nightfall of day one finds us in the high desert town of Mojave, nine hours and 430 miles from home. Desolate and whipped ceaselessly by winds down out of the mountains, this place would be an ideal setting for an angst-driven indie film, and also a good place to ride into while wearing a black duster. As it is, the Special’s cinematic enough, especially with the leather handlebar bindle attached—which in some weird way looks exactly perfect on this machine, and besides adding stowage capacity does a commendable job of taking some wind pressure off the torso. Mojave also appears to be where all hitchhikers finally run out of luck, and my audience of onlookers is mostly a forlorn gauntlet of weathered vagabonds. The Special is an apparition here, and I have the distinct sense of being some kind of sci-fi scooter tramp riding back from a post-apocalyptic future.

The Mother Road—and some more limits

If Mojave conjured up a postapocalyptic future, the route east of Newberry Springs conjures up a horribly desecrated past. This is where Historic Route 66 stops being a route at all, and deteriorates into a battered and humiliated vestige of The Mother Road. And the Special is not happy about it. There are several things it’s not happy about. The suspension is not happy about the constant pounding over what remains of the asphalt. The 240 Dunlop is not happy about sidestepping the chunks. The Revolution is not happy about the heat, which would be over 100 degrees in the shade, if there were any, which there isn’t, and what’s more it’s absorbed and intensified by the black rubble of ancient lava that constitutes the landscape here. The cooling fan keeps the motor viable, but it’s working overtime. Thank God I’m not wearing a black duster.

So much for nostalgia. We can endure this hell for only so long, and when the first opportunity to get away from Mother and over to I-40 presents itself an eternity later, we take it. When again we set off on Route 66, it’s to take the wide southern arc through Amboy to Needles. There, things improve dramatically, and there the Special gets to flex its muscles and race along for empty miles at three digits. The Bike’s longish 34-degree rake up front tracks like a bullet train at those speeds, and the only thing that keeps me from running wide open is my skittishness about how the bags and bindle might affect handling at those speeds. We do not need a tankslapper out here in the blistered middle of nowhere.

Leaving Laughlin; the longest day

It’s been a 500-mile day… almost. We fell a half-mile short of that figure, and I briefly considered riding around in the parking lot of the Topaz Lodge until the tripmeter turned over, but the hell with it. Over the course of the day’s ride, we’ve experienced a 50-degree variation in temperature, and a 7,500-foot variation in elevation. Another bloody hot dash across the Mojave Desert out of Laughlin segued into a long lope up Highway 395 from Kramer Junction to Topaz Lake, running between the 14,000-foot peaks of the Sierras and their 10,000-foot counterparts on the Nevada side and taking a sound thrashing from crosswinds. The Special charges on through all of it unfazed, unflappable, and I remain physically unfazed as well, without the slightest symptom of monkey-butt, spine-lock, shmush-guts, digital numbness, Jake leg or incontinence. But it was on the downslope of 8,000-foot Deadman’s Pass near Mammoth Lakes that the sky went from a perfect blue to an ominous sheet of gray, and in seeing that development, something unnerving occurred to me: the calendar. In my fevered haste to escape the oppressive heat of the desert and seek relief in the high country, I’d completely overlooked the fact that this was April. And that no sane motorcyclist counts on getting over a high Sierra pass in April. May’s usually sketchy. Some years, even June’s a gamble.

What the hell was I thinking? The high-pressure bubble that had brought record heat to the region could break down at, literally, any moment, and there we’d be. Utterly cut off and forced to retrace our route for hundreds upon hundreds of miles. We could, of course, get while the getting’s good and try to scoot up over the summit before the weather can take a turn, but after nearly 500 miles, and with the darkness descending, that undertaking didn’t hold a speck of appeal.

No, we would lay over at Topaz Lake and take our chances come the morning. If only a little snow fell at the higher elevations, we could manage that. By now there wasn’t a nuance about the Special’s handling I wasn’t attuned to, and I had absolute faith in the bike’s road savvy. Let it snow. And that’s the way the mind works after a really long and grueling day in the saddle.

Road karma

Come morning, the bubble has held, and the dark clouds have cleared away. And in the early chill I pack up the Special and we set off up into the Sierras, snow lingering in every shadow, winding over roads still wearing the rockslide road debris of winter. Climbing over at Monitor Pass, and again at Echo Summit, temperature in the 30s, alert for the dread black ice. Vistas unfold at every turn, and that special ecstasy that the road delivers only to the touring rider comes over me. The long descent to the valley below begins, and of the many things I know about this bike after 2,500 adventurous miles all told, what I know best right now is that I don’t want to return it to the Fleet Center.