After 75 Years of Peace, France Hosts its First-Ever Vintage Beach Races on Hallowed Ground

Words by Kali Kotoski

Photos by Stefan Sell, Virginie Petorin and Jack Høier

“Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force:

You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months.

The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you.

In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped, and battle-hardened. He will fight savagely.”

— Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower delivered to U.S. forces on June 5, 1944, the eve of D-Day, as over 2.8 million Allied troops lay in wait on England’s southern shore.

Two years after German forces swept through Paris, Adolf Hitler ordered the construction of the Atlantic Wall—a coastal defense and fortification system that stretched along the coast from the Spanish border up into the northernmost latitudes of Scandinavia, according to Nazi propaganda. Concerned over a spate of small-scale incursions by light commando units, Germany aimed to permanently wall off vast areas of continental Europe with cement, steel and soldiers manning colossal coastal guns, batteries, mortars and artillery.

By 1944, France’s 800-mile northern coastline had seen the greatest development of the wall. Built primarily by forced labor, some 8,000 defensive bunkers and German pillboxes lined the shore with Panzer divisions inland. German troops are estimated to have laid as many as six million mines and 5,000 beach obstacles.

At three in the morning on June 6, 1944, an Allied aerial and naval bombardment commenced along a 50-mile stretch of Normandy, dropping imprecise bombs in overcast conditions and launching massive artillery shells from destroyers as close as 1,000 yards offshore. Soon after, paratroopers were dropped – again, imprecisely due to cloud cover – inland to help secure beach exits and to secure bridges, and at first light the first of some 156,000 troops began landing on French soil, from Utah and Omaha beaches to the west and Gold, Juno and Sword beaches to the east. The effort constituted the largest invasion force the world has ever known.

At a little after 7am the first wave of British troops waded onto Sword Beach – the easternmost landing site of the invasion – along with Canadian, Polish and Norwegian soldiers. Led by Lieutenant General John Crocker, who previously had mixed success in North Africa and took a piece of shrapnel to the chest during a training accident in Tunisia, the troops were tasked with taking Sword in hopes of allowing the 3rd Infantry Division to capture the historic Norman city of Caen.

German snipers had taken up posts in abandoned holiday homes and pillboxes along the relatively flat and exposed beach. The entire stretch of coastline was filled with hedgehogs, barbed wire, mines, wooden stakes, iron crosses and dragon’s teeth. Above the beach a network of twenty strongpoints put down steady small-arms fire against the lightly armored troops, many caught defenseless in the traps. Further back, howitzers barked grey smoke, and from a ridge three miles away the 21st Panzer Division showered artillery on the men.

Even as allied casualties mounted (especially at Omaha), most amphibious DD tanks landed unscathed at Sword, and the area was eventually secured. Engineers cleared the exits to the beach. Six-hundred-and-eighty-three Allied troops were dead. The Germans lost 50 tanks and six bombers with untold casualties. Fortunately, Erwin ‘The Desert Fox’ Rommel was in Germany visiting his wife, while the commander of the Panzer division was conspicuously in Paris.

Allied forces had breached the Atlantic Wall in a matter of hours. The city of Ouistreham was partially leveled and Caen was not captured until three days later. Between Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword, over 20,000 soldiers from both sides were dead and the biggest armada in the history of the world launched the push that liberated Europe in 11 short months.

John Crocker was “assigned the most ambitious, the most difficult, and the most important task of any Allied corps commander during Operation Overlord,” wrote historian Douglas E. Delaney.

Now, 75 years later, Ouisterham is a charming resort town with a casino, rebuilt to retain a quiet historical pre-war feel. A five-story German bunker from the Atlantic Wall remains and has been turned into a museum. A wide boardwalk leads down to Sword Beach where visitors picnic and tan.

It was 7am on September 21. The beach was white and clean and the racetrack was lined with square hay bales. The weather was a pleasant 75 degrees and the sky was clear.

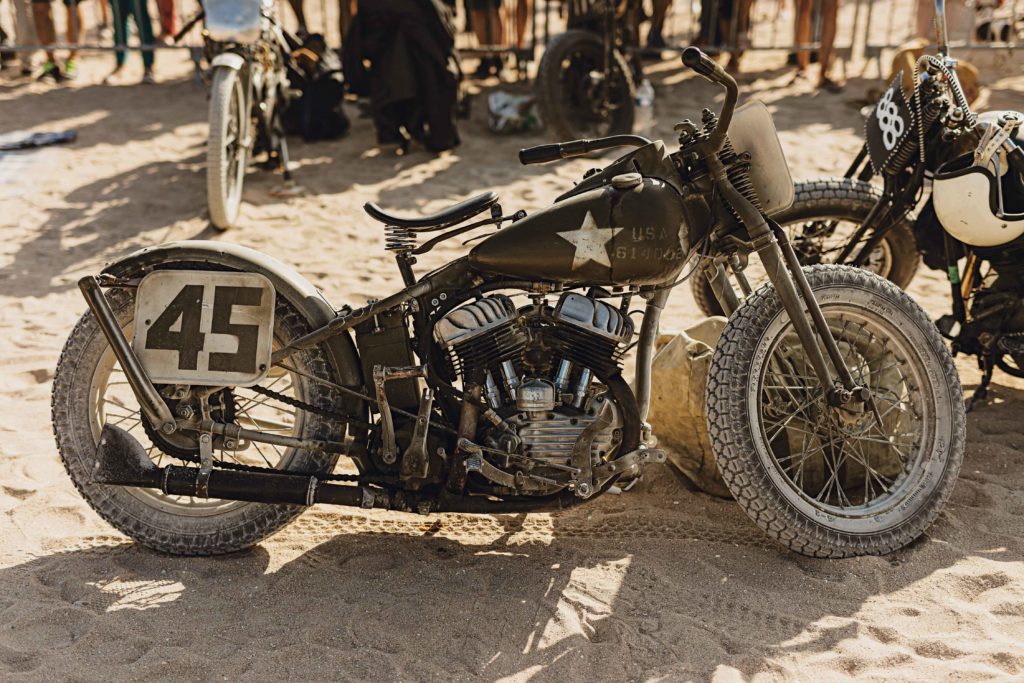

Oklahoma’s Chris McGregor walked the dark beach the night before, shortly after landing. He had raced his 1942 Harley-Davidson WLA weeks prior on the Danish island of Rømø with mixed results, returned to America to attend his daughter’s wedding, and was back to race. His bike, entrusted to Steffen Gödecke of Harley-Davidson Hamburg in Germany, had yet to arrive as Gödecke drove through the night, crossing the Seine before daybreak.

The duo was together again to participate in France’s first-ever vintage beach race on the sacred beaches of Normandy where only pre-1947 motorcycles and cars are allowed to compete.

“Maybe my bike landed here before, or at least its brothers did,” said McGregor. “That was something that was constantly in my head.”

Harley-Davidson produced roughly 70,000 WLAs and its heavier cousin the WLC during the war effort. Nicknamed the “Liberator,” it was used extensively in Europe, carrying time-sensitive messages or letters from home, as well as performing Military Police duties.

During Rømø, the bike performed just okay. It was hard to start and frequently misfired, making it sluggish and heavy on the soft Danish sand. And during the weeks between the races, Gödecke had plenty of time to play around.

When the flag girl dropped, McGregor’s front tire lifted off the sand with the back tire catching traction; first gear and full throttle. Reaching approximately 82 mph at the end of the 1/8-mile track, the competition was an easy seven or eight bike lengths behind as McGregor stood on the brake, going a considerable distance before he could turn. The nearly 14,000 strong crowd went wild, cheering him on in the return lane.

“I didn’t lose a single race the entire day, although there was a rough spot in the track where I almost lost everything,” McGregor said. “But the bike performed well.”

Little did McGregor know that Gödecke had made some considerable changes to the bike. “The bike was a pain in the ass to start and I had no idea it was misfiring at all speeds. When we first had the bike delivered, I did not know the bike yet,” Gödecke said.

So in between Rømø and Normandy, he realized that the bike was not burning European fuel properly and he put in new spark plugs, adjusted the ignition points, carburetor, point gaps and learned about the properties of a magneto. With the help of his mechanic Hiroshi, they set it up on a dyno.

“It was funny to have both a German and Japanese man working on an American bike to be raced at Normandy,” Gödecke said. “But the dyno didn’t work because it couldn’t handle the starter. We measured 46hp at 3500 rpms but then the dyno said ‘nope.’ The bike is still a mystery to me.”

Back at the track, racers and spectators from Rømø took notice of the changes.

“One guy was like ‘I don’t know if it is the bike or the balls winning these races,’” McGregor said.

At one point during a very French bag lunch that included bread, foie gras, some meats, cheese, fish, a glass bottle of Coca-Cola and red wine, some race officials were concerned that McGregor was going too fast. Sword Beach is not made up of sand, but finely ground seashells and limestone that creates a soft, thin, dusty layer of chalk. Beneath that, the ground is as hard as cement. In substance, the beach is related to the White Cliffs of Dover across the English Channel.

With the track all beat up, McGregor started to hesitate on his next race and he felt a bit of fear.

“I thought get that out of your head and run your race. I almost slipped up because of someone telling me how to race. The hesitation, you can mentally crash. If I hadn’t pulled my head out of my butt I would have physically crashed,” McGregor said.

Gödecke saw it differently. “Many of the guys have never ridden on the sand. All you need is long legs, arms fully extended and with a full-throttle you can ride through the soft spots,” he said.

“It was no slaughterhouse, but Chris slaughtered the competition. His little bike was the fastest bike on the beach,” he added.

Professional German photographer Stefan Sell went to capture the event. He has been shooting vintage beach races for the last decade and has seen the sport proliferate. It used to be just eastern Germans wrenching on old bikes and racing. Now, it is spreading to Scandinavian countries and throughout Europe.

“I get the same adrenaline as the racers when battling to get shots. Of course, it can get a bit dangerous but you have to stay calm,” he said. The Normandy race for Sell was very important, as the location resonates still in day to day life. “I am a believer in the European Union and it all started right here,” he said.

By the end of the day, the significance of racing on this blood-soaked beach where 638 Allied soldiers died on the sand or in the waves, was on the forefront of everybody’s minds. Despite the revelry, the solemnity of Normandy could not be ignored. McGregor and Gödecke had thought about it long and hard before the race, but after it was a bit different.

“When you go to a place where so many good people died especially with old bikes and cars, you can imagine them. If all those good people hadn’t died, we wouldn’t be able to do this,” Gödecke said.

For McGregor, his feelings manifested as a celebration of life, history, honor and that collective, yet individualistic, sense of gratitude built off a humbling and shared experience that spans generations.

“I have really lived. That is kind of how I felt after Normandy. I can tell my granddaughter I really lived,” McGregor said. “I met some older gentlemen there and they said that their dads, waking up the next day after D-day, said you will never feel so alive as the day after you survived a battle.”