Affordable rebellion

A classic case of less-is-more

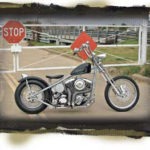

When it was time to pick up Desperado Motorcycles’ Good Times Bobber, the day was overcast with a high percentage of the wet stuff expected. Since it was a new and unfamiliar bike, I did the unthinkable—I borrowed a truck and trailer and made the decision to haul the Bobber instead of ride it. After loading up the bike at Desperado’s compound south of Conroe, Texas (and despite the embarrassment of trailering), I elected to go ahead with plans to visit a nearby swap meet. And although the swap meet was featuring a bike show, the Good Times Bobber soon garnered its own crowd of curious onlookers. I was quickly hit with a multitude of questions that I fielded as best I could, considering that the only “ride time” I’d had was from Desperado’s shop doors to the trailer. My only thoughts were, “If this machine’s simplistic and classic style gets this kind of attention on a trailer, what’s it gonna be like once I get it on the road?” I couldn’t wait… literally. Halfway back to the office, I stopped and dropped off the truck and trailer and rode the rest of the way in—to hell with a little nasty weather.

The late ’60s and early ’70s saw a boom of activity in the motorcycle modification “movement.” Altering bikes to fit personal taste had been going on for years of course, but this time period received a big shot in the arm with the release of the movie “Easy Rider” in 1969 (along with a bevy of B-rated biker flicks that followed in quick succession) and a bunch of custom motorcycle magazines hitting the shelves that were an inspiration to every shade tree builder with a torch to change something. Soon, we all had the fever. And everyone wanted a rigid. Problem was, the only frames available without a rear suspension package were original Harley units.

The Motor Company produced rigid frames for their Big Twins up until 1957. The versatility of the H-D frames allowed the placement of just about any power plant in just about any year frame. So in 1969, it wasn’t difficult at all to stuff a new Shovelhead motor into a much older Knuckle or Pan rigid chassis. But the primary rigid frame of choice were those manufactured from late 1954 through 1957, the venerable straight-leg. Up until mid-’54, the front downtubes on all Harley frames were what was known as wishbone frames. Because of its clean lines and limited availability, the straight-leg became the most sought after, but it was fetching quite a princely sum back then, sometimes as high as $300. (Go ahead and laugh—just remember that gas was going for 35 cents a gallon then.) Once you were able to nab one of these sacred straight-legs, all that was left was to slap a flat fender on the rear, a Sporty tank up top, a 21-inch wheel up front and add some drag pipes. After tossing on a bedroll (’cause no one would rent us a room), some throw-over leather bags, a bota full of grape and a cute gal in hip-hugger bell-bottoms, you, my friend, were ready to go. The times were simple. The times, they were good.

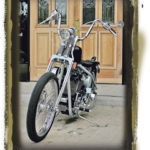

Jeff “The Desman” Nicklus is the founder and CEO of Desperado Motorcycles (desperadomotorcycles.com) and remembers that particular chapter of American biking—back when simple bikes ruled the asphalt. He designed the Good Times Bobber to be a true exemplar of those days. The proprietary straight-leg frame sits a scant four inches off the tarmac, has a 34-degree rake and no stretch in either the downtubes or backbone rail. It is heli-arc welded and allowe to cool in the jig to maintain alignment, and then stress relieved.

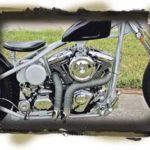

My test bike was issued with a handsome silver frame (powder coated) that stood out in sharp contrast to the gloss black tank and fender. About the only things the Good Times Bobber chassis lacks as an exact duplicate of its ’57 brother are sidehack loops and a crossover support tube for the mechanical rear brakes. (Nicklus is not that much of a purist and runs a two-piston dual- action rear brake by GMA. Front stoppage is also supplied by GMA with a single-piston, dual-action unit.) While the bike furnished to me during this review relied on a 100-inch Rev Tech to spin the back tire, after a recent agreement with S&S Cycle, all future Good Times Bobbers will come stock with the S&S 111 c.i. motor, available in either natural cast or with a chrome accent package. Upgrades include 117 and 124 inches. Fuel is fed via an S&S Super G carb, while the exhaust is dumped through a choice of three different Desperado pipe configurations. (The black exhaust tape on my model hearkens back to the days of street racing.) The primary drive consists of a three-inch Primo belt drive connected to a Desperado 6-speed with close-ratio, full-sized back-cut gears, 6061-T6 billet aluminum trap door and Desperado chromed billet side cover and top cover. Final drive is chain.

The DNA springer comes only in stock length and does a decent job of smoothing out the road bumps. It is available in either chrome or black powder coat, has hidden fork stops and is adjustable for rebound. At the bottom, a 21-inch ribbed Speedmaster is wrapped around a Hallcraft spoked wheel assembly. On the top of the springer, 12-inch apes connected to three-inch risers provide comfortable access and ease of control. Following in the tradition of the ’60s, the wiring is left exposed and not run inside the handlebars. Illumination is by a clean Desperado billet unit, while the only instrumentation (a small speedo with odometer) is an Auto-Meter component.

Under the abbreviated Desperado flat fender sits an Avon MK II 5.00 x 16. In the ’60s, this was the largest tire available (unless you went automotive) and was the only one appropriate for this rendition of a classic bobber. This is a high-profile tire with somewhat of a square configuration. By lowering the tire pressure from the recommended 35 psi to 25, both the handling and the ride greatly improved (an old trick from earlier days). Atop the fender, a limp sausage taillight assembly is flanked by twin mini-markers that provide the minimum amount of lighting allowed by law. The four-quart round oil tank is a Desperado unit and is also home to the 545-amp battery needed to turn this brute over.

A no-nonsense machine, the Desperado Good Times Bobber accents its raw heritage and leaves its mechanicals exposed instead of obscuring them with sheet metal. While this type of styling flies in the face of some industry contemporaries, the use of a car-type key starter switch, the absence of axle covers and the use of rubber hose for oil lines all lend honesty to the bike’s legacy. And that’s part of the beauty of this motorcycle—its ability to carry you away to a time before $5,000 paint jobs and air-ride systems became mainstream. Back when it was just a frame, a couple of wheels, a big-ass motor and a rider twisting the hell out of the grip. You can’t get more honest than that.

The tiny LaPera seat is actually a lot more comfortable than one would first think. But a small lip along the back would be nice and instill a bit more confidence when hammering it (you grab a fist full of throttle on this thing, you better have two hands full of handlebar). With a wet weight of only 517 pounds and a motor cranking out an excess of 100 hp, the power-to-weight ratio is crazy (but crazy in a good way). Just be forewarned that not much of that “wet weight” has to do with the bike’s gas capacity. The Sportster-styled, scalloped tank is a Desperado original but features a high tunnel that is fitted low on the frame, which equals about a two-gallon capacity. With a big-inch, petrol-devouring engine, you will find yourself taking hourly pit stops—just like in the ’60s.

The Good Times Bobber comes with a 12-month/12,000-mile warranty on the overall bike, three years or 36,000 miles on the motor and a five-year/50,000-mile guarantee on the transmission. And with a starting price of only $19,995, the Desperado Good Times Bobber invokes images of an affordable age—bring on the miniskirts and knee boots.